As promised I am sharing a story I wrote for the just published Dark Mountain anthology, Dark Ocean. It’s a logbook of sorts from a creative residency I hosted aboard a boat called Merlin in the Hebrides last year, and was the inspiration for this sea-themed issue. You can read more about the issue in the bookshelf section at the end of this introduction.

The Voyage

What happens when you leave your ordinary life behind and put your attention on the vast mysterious being that surrounds our homelands in a time of disruption and loss?

I want to take you north, to the Outer Hebrides, one warm evening last July, to a boat called Merlin, as she sits in an island harbour, sails furled, ready to leave. We are going on a journey that is an endeavour, and also a dreaming. It is a voyage that underpins this book you now hold in your hands. I am writing this as one of her crew of artists and writers gathering that day for a Dark Ocean residency, to dive into the myths and narratives of the ancestral sea, to connect with the fish, birds, winds, rocks and tides of the Western Isles, our own creaturehood, our deep sea-memory.

CHART Stornoway, Lewis

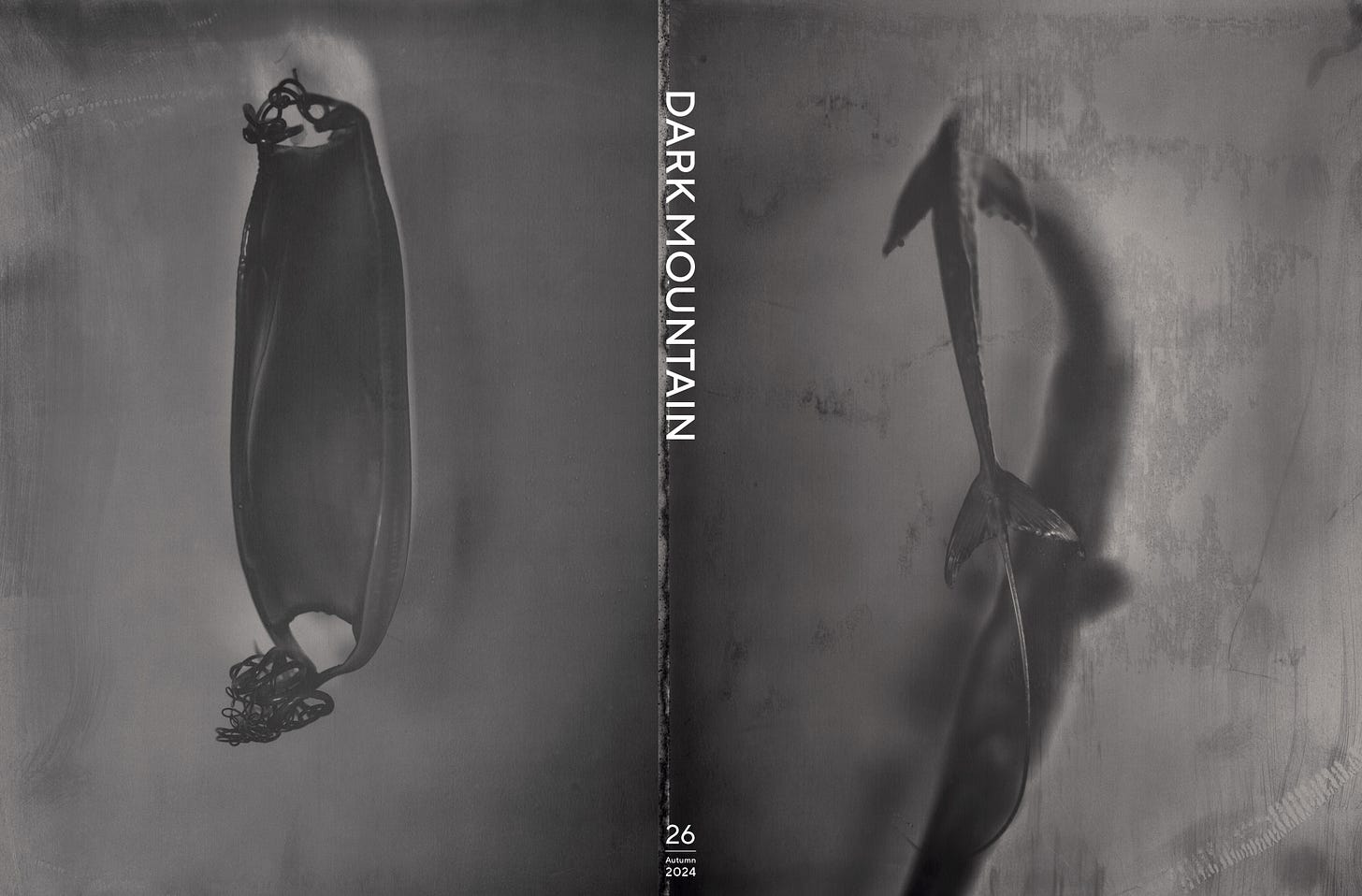

There are nine of us below deck, drawing up a map on a large piece of brown parcel paper. On one half of the map, we list what we love about the sea and on the other the facts about what is happening to it and all its creatures. There is a ring of chalk circles in the centre, marked self, kin, dreaming, that sits as an interface between them. And a collection of objects we brought to introduce ourselves: a pair of ship’s dividers, a mermaid’s purse, a fossil, a frond of seaweed, a stone, a feather, a luminescent shell. We pick up coloured crayons and cover the paper at each end of the table with words. Then we change places.

awe, wonder, cleansing, metaphor, strength, transformation, space, presence, breath, immersion, dolphin, change, dive, swim, nourishment, selkie, liminal, wild, life, horizon, salt, rhythm, sound, movement, connection, mystery, regeneration, home

acidification, microplastics, polar ice melt, deep sea mining, bottom trawling, dredging, naval warfare, power lines, sonic pollution, salmon farming, human trafficking, dead zones, shark finning, oil spills, Niger Delta, Bikini Atoll, coral reef bleaching, tourism, cruise ships, container ships, overfishing, culling, warming, Seaworld

How can we hold both these lists as we create our work? This paper will be our chart, I say, and these objects, our portals, our way into the deeper dimensions of the places we go to. The sea beneath the sea. Each day we will look at our journey in terms of these chalk layers, through one of these portals, and explore them together.

BIRD The Shiants

There are nine of us up on deck, shuffling, sliding, stepping over coils of rope, getting a feel for the pitch and yaw of the boat, as we head to open sea in a stiff westerly breeze. Open hatch, close hatch, buckle, cleat, knot, unfurl, hoist, pull down, pull in, harder, tighter, tie, secure, watch the boom, lee-ho! Dolphins! Where? Over there, a pod, and a whale, and guillemots diving! And what, oh puffin!

Geraldine is balancing on the cabin roof, fixing an etching device made with heather root to catch the shape of the wind on a copper plate. ‘When we talk about weather, we talk about wind. We don’t talk about rain’, says Oliver sternly, as he runs through the safety drill, and then tells us about the Blue Men of the Minch. These mythical ‘storm kelpies’ demand that the captains of boats who cross their domain complete a verse of poetry – in Gaelic – or they will try and capsize the vessel.

Today however, the sun bounces off the dark water, as the rocky coasts of Lewis and Harris slide by, and we have our first lesson in crewing this expedition yacht, named after the fleet falcon. Most of the crew have sailed before and leap to the winches, take the helm, glance at the mainsail with a critical eye, adjust to the wild and fickle currents of these waters, as we head out to the Shiant Isles. Slowly over the long hours, the great basalt pillars appear on the horizon.

Chart in hand, it’s hard not to feel powerless as the tsunami of facts about the ocean creatures press on all sides: the disappearance of 90% of large fish, the poisoning of mangroves by shrimp farms, the destruction of sea beds for shellfish, jellyfish blooms, algae blooms, seabird populations crashing in the Hebrides, whales washing up in their hundreds in New Zealand; the last vaquita caught in an illegal net in the Bay of Cortez, bycatch of Chinese medicine makers in search of the swim bladder of the endangered totoaba.

But then, here are the dolphins playing in the wake of the boat, leaping alongside, looking at you. Showing their white bellies. And puffins bobbing on the water, miles from land. It’s hard not to start the story here in this state of being, immersed in this elemental, finned and winged world, all this light and space, where the aliveness and intelligence of everything comes so close.

It would be easy to make a beautiful book of kelp forests and seagrass meadows, hewn from driftwood and luminescence, from plankton and seahorses, from the world’s marine sanctuaries, the grandeur of this landscape, but we are on the Dark Ocean watch, where the facts of a predatory civilisation cannot be edited out. It will be an alchemical book, the dark material we find turned into gold by our creative attention, I tell the crew. Merlin will be our hermetic vessel.

We arrive at our anchorage at sundown, a stony saddle between the islands, through a cathedral of flying birds, thousands of puffins and guillemots, razorbills and shags, moving between the ocean and their nests among the crags. The grassy slopes are full of flowers. It’s one of the most beautiful places I have ever seen in my life. Alex catches a large fish for supper. It’s a pollock, a fish now eaten as a substitute for the disappearing cod. Jellyfish with scarlet stomachs drift by the boat. And beneath them, waiting, unknown to us, a shark.

KELP Loch Bhrollum, Lewis

The seals are singing as we enter the loch. They lie in heaps on the rocks and watch us, as we glide through the still water towards a small beach at its far end. It’s a sad place, Oliver says, and tells us how last week when he came, everyone was haunted by dreams. The beach is ringed by deserted houses and broken walls. Like many places in the Highlands, it was devastated by the British empire, its communal clan culture and mytho-poetic language deliberately broken, and its people driven out to the New World during the Clearances, to be replaced by sheep and shooting estates.

Bhrollum was cleared in 1840, also due to the decline of the kelp industry. The giant fronds of seaweed were once collected, dried and burned by thousands of people along these Hebridean shores. The powder was used for glass and soap and gunpowder. A dangerous, stinking, hard labour that collapsed after the Napoleonic Wars.

The shore is impossible. The rocks are slippery, the grassy slopes are slippery, there are underground streams, everything is at an angle. My gumboots have no grip. It’s raining. The midges are coming. I sit down on a rock and swear a lot. The village seems miles away.

‘Come on’, says Mike. ‘We are here for something.’

He is right. I don’t know what yet but I follow him: slip and stagger on to the first houses, wait in the rain, then turn back. That night after supper we tell stories about our ancestors’ dispossession, from England, from Ireland, from North America. And we begin to sing: sea ballads and land laments, and then, protest songs. Mike gets out his small ship’s guitar and we roar out Woody Guthrie’s famous anthem:

Good-bye to my Juan, goodbye Rosalita

Adios mis amigos, Jesus y Maria

You won’t have a name when you ride the big airplane

And all they will call you will be ‘deportee’.

That night none of us has nightmares.

STONE Wizard Pool, South Uist

What does it mean to be kin? For the sea creatures to teach us about breath, about life?

We’re crossing back to Lewis. Mara, anarchist sailor and activist, reads out a chapter from poet Alexis Pauline Gumb’s Undrowned. It is about the Steller’s sea cow, the first marine mammal made extinct (within 27 years) by seal fur hunters in the Arctic. A vast and gentle being whose hearing extended for miles.

What can I do to honour you, now it is too late?

I will remember you […] I will say, once upon a time, there was a huge and quiet swimmer, a plant-based, rough-skinned listener, a fat and graceful mammal. And then I will be quiet, so I can hear you breathing. And then I will be breathing, and you will remind me, do not rush. And the time in me will hush. And then we will be listening for real.

As we approach our next anchorage, we pass by a round metal construction by the rocks. It takes us about a minute to realise that it is a salmon farm.

I didn’t feel disturbed at Loch Bhrollum but this place feels foreboding. We do not go ashore.

As we set off the next morning, a sea eagle observes us from a high crag. The salmon leap out of their sea gulag, crash into the net roof and fall back, their huge mutilated silver bodies, catching the light, miles from the rivers where once in their wild form, they were born, lived, ran to sea, returned against the flow, and spawned. Where once they were honoured by the people as a peerless alchemical creature, teaching us everything about Earth’s feedback loops with their lifecycle. Whose bodies, even in death, fed the once-forested land.

KELPIE Loch Scavaig, Skye

‘How is your Gaelic?’ I ask Oliver, as we head into lashing rain and hook ourselves to the deck.

Myth is a hard thing to take seriously for modern grown-ups. We had laughed about the Blue Men, as we crossed the Minch. But these things are real. Because you need another language to access the numinous and the mysterious, and the sea is not the land. You might master a boat, but not the ocean. All seafarers, all wild swimmers, know that in the core of their beings. To speak with the sea requires a different sensibility from us.

In Voices from the Old Sea, his testimony of the Costa Brava as it fell into the clutches of tourism, Norman Lewis writes about the Spanish fishermen who would recount their experiences in blank verse on return to shore. Poetry can access that language for individual readers, but only ceremony can do that for a group of people. I’m asking everyone to create a ritual that will say thank you to the sea that is bearing us.

When we arrive at Skye, we hunt for seaweed about the rocks for a final supper risotto. I find two perfect lobster claws. ‘Gift from the otters’, says Cally, as we set off for Loch Coruisk, just inland. Geraldine brings her paints, and sitting on a giant shard of granite, we draw the loch ringed by the vast and brooding Cuillin mountains, waterfalls tumbling out of crevices, and its famous kelpie, a dangerous lake horse that drags the unwary down into its dark depths.

‘Let’s swim,’ I say. The Kelpie won’t mind us. Three of us swim naked out into the cold and sweet water, it feels so clean and strange after the salt, smooth against the skin. I feel I could swim forever. Maybe that’s the Kelpie’s warning. That going too far into the dreaming of places could pull us into a state which feels so much more kin to our beings than dry land. There’s a longing there, but as all fairy tales instruct us, do not be lured, do not tarry, we cannot live there as humans. Our place is elsewhere. We have work to do.

Back on board. I take up the fishing line, tangled by the pollock, and try to loosen and liberate its many knots. It’s my third day of trying.

LINE Kinloch, Rum

‘We need to get out of here’, I say. We are in the courtyard of Kinloch Castle. A massive turreted red sandstone mansion by the shore, surrounded by abandoned gardens, with huge dark dusty rooms, a grand piano, a stuffed eagle, library, ballroom, billiard room, like some real life game of Cluedo. Its atmosphere is unbearably oppressive. Like many grand Edwardian houses, the castle’s famously debauched fishing and shooting parties fell silent in the Great War, when only two of its fleet of household servants returned from the trenches. Sir George Bullough inherited the island with a vast fortune from the weaving industry, and built the house to entertain his famous guests. Now the cost of repairs is too high, and there is a discussion about pulling it down.

Back at the boat, I attempt to finish untangling the line and realise I cannot. Our history of power and privilege catches us unawares like a turtle in a dragnet. Bound forever to repeat itself in an entropic loop and drown the world.

Sometimes to regenerate you have to bear witness, sing to the dead in a place of silence, make a wish in your heart for an imprisoned creature; and sometimes you have to peer through the windows of a dark house, and not be lured in. Hold fast and let go. A storyline that is too tangled to ever become straight.

HOME Full sail to Mallaig

We are on the long haul back to the mainland, running with the wind behind us. Geraldine has placed her wind-etched plate in the wake of the boat to catch the memory of water. Tonight we will drag a fine-meshed net to catch plankton, and see how much life there is moving and interacting in a few drops of seawater. We will share the week’s work: notebooks of poetry and paintings, the shapes of the islands, the light in the water, the light of the sky, our dreaming map of colours on the other side of the brown paper chart. Mara will tell a story about a future ancestor she heard on the mountain.

You know, Alexander will say, we need all these charts and equipment to navigate the sea. But a seal just dives into the water and knows exactly where he is with his body. Maybe that is what these islands, this voyage, have taught us. If we just dared to immerse ourselves in the great memory of the sea, we too would remember where we are, how it is to live on this blue planet as a real human being.

This small log is written from memory: from what remained when we returned to dry land and our temporary pod dispersed. The big issues and small observations of this book were seeded in these listening circles on board Merlin, shaped by our creative endeavours to remember our salty origins, to start again and become future ancestors. It honours a time when nine people put their attention on the wind and the waves, living in harmony in a tiny space, laughing, singing, sleeping, breathing together, cooking and eating together, our arms flying in all directions across the cabin like an octopus. It travels from the seabed to the horizon, from birth to death, following an alchemical line, running like Geraldine’s plate from the nigredo of the world towards the light, wresting beauty and meaning out of shadows.

As you grow older the heart’s desire loses its fire, and yet there are still encounters with this luminous Earth you wish for. My own fiery wish was to return to these islands which feel like a place of ancestors (my grandmother was from Aran), and then another was to sail a boat, to feel as I do now what it is like to steer a crew homewards, to sense the helm in your hands, adjusting the boat on its course, as the waves and the wind and currents push against the sails and hull, your eyes on the coast ahead.

Years ago when I was young I had sailed a sky-blue caique out of a cove in Turkey, where the first naked statue of Venus was brought from Athens to a small temple above the rocks. The Mediterranean deity had emerged out of the waves, with two dolphins as her companions, as they were mine that morning, leaping either side of the boat, my bare foot on the tiller, the men sleeping below deck, the sun rising over the sea. I felt I would never be as happy as I was in that moment, when the myth, the land, the sea, and my own being merged so completely. Maybe all my small voyages out in this life have been to bring these things together, to create a harmonic that the goddess of love and beauty and justice would smile upon. Maybe if we had chosen to sail alongside this sea-borne female deity, instead of worshipping desert storm gods, there would have been less strife in this now falling world.

But now we are on the voyage home. It is the end of something, and also perhaps a beginning. And it is my hope, as its navigator, that this Dark Ocean vessel reflects that mood: that the portals in these pages you hold in your hands – a broken clam shell on the ribbed sand, a coconut husk, the transcript of a whale song on blue fabric – take you out into the heart and imagination of the sea; that, as your senses glimpse on the horizon, the plume of smoke of what was once the Bikini Atoll, the cry of drowning migrants in the Libyan sea, the absence of the cod on the banks of Newfoundland, it is possible to face what a return voyage home now asks of us.

It has been a great joy and privilege to have sailed with the crews, both on Merlin in the Hebrides, and with my fellow editors alongside their native seas: Siana Fitzjohn (Pacific, New Zealand), Neale Inglenook (Pacific, California) and Joanna Pocock (Atlantic, Canada). I thank them and all our contributors for creating this sturdy and beautiful Dark Ocean vessel. I wish you, our readers, fair winds and happy soundings as you set sail into our salty, windy, sun-bleached pages. Kalo taxidi (καλό ταξίδι).

BOOKSHELF

Dark Ocean is a collection of essays, stories, artwork and poetry, praise song and meditation, based on last year's Dark Mountain residency. Like all Dark Mountain books, it is steered by a troubling paradox: the collapse of a world we have known, and the emergence of something recollected from the ruins. Our challenge as writers and artists was to create work that could hold both the peril and plunder of the ocean, as well as our love and wonder for the matrix of all life on Earth.

Our paper vessel now sails out across the world's oceans, carried by currents across power lines and ghost nets, through storms and oil spills, plankton and giant squid, into the far Pacific, swimming by the foggy Californian shore, following in the wake of a Greenland shark, the song of a humpback whale, a floating coconut shell in the rising Indian Ocean, the nightmare of migrants in the Mediterranean, a dreaming of Doggerland under the North Sea, of a vanished ocean in the desert in Utah.

And a goddess who once came to the Aegean from the starry deep to teach us about love. And a selkie with eelgrass hair who speaks with you at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay.

But it began in a quiet harbour on the island of Lewis on the edge of the Atlantic ...

You can buy Dark Mountain: Issue 26 – Dark Ocean in our online shop. A selection of pieces from the book will be published over the next few weeks online. Follow in our wake here.

The Dark Ocean expedition on Merlin ran from 8th–15th July 2023, organised by Sail Britain. The crew were: Oliver Beardon (skipper), Alexander McMaster (first mate), Charlotte Du Cann (Dark Mountain navigator), Hannah Close, Geraldine van Heemstra, Mike Hembury, Mara Murphy, Mirja Timm, Cally Yeatman.

Thank you for reading everyone. Red Tent will be back at Samhain (31st October) for news of another new publication for our metaphysical bookshelf.

So beautiful, thank you 🙏. Especially loved these:

“kelpie, a dangerous lake horse that drags the unwary down into its dark depths.

‘Let’s swim,’ I say. The Kelpie won’t mind us. Three of us swim naked out into the cold and sweet water, it feels so clean and strange after the salt, smooth against the skin. I feel I could swim forever. Maybe that’s the Kelpie’s warning. That going too far into the dreaming of places could pull us into a state which feels so much more kin to our beings than dry land. There’s a longing there, but as all fairy tales instruct us, do not be lured, do not tarry, we cannot live there as humans. Our place is elsewhere. We have work to do.”

“we need all these charts and equipment to navigate the sea. But a seal just dives into the water and knows exactly where he is with his body. Maybe that is what these islands, this voyage, have taught us. If we just dared to immerse ourselves in the great memory of the sea, we too would remember where we are, how it is to live on this blue planet as a real human being.”

Thank You Charlotte, it is now an impossible dream to coax the sea - or at least just become a passenger to some oceanic travel - a witness as to say... this reading spawned the imagination in a direction that may best serve my bodies limits - and perhaps encourage a strengthening towards what lived experience is allowed by me. I wish to swim as Kelpie, as Seal bound warmth in the tides... a desert rat that cannot handle the cold...

As I wish upon a bodies scope - for another life... I feel, you are living on behalf of us - lost to the heart's desire...

Thank you - sincerely - for living. and living the call...