Territory

Engaging in a land (and sea) based practice

What is the ocean dreaming now? I asked Mark. It was a question I had just heard in a lecture called The Aboriginal Dreamtime. The speaker, an eco-psychologist called Stephen Aizenstat, had told us that the dreaming of the Earth and all its creatures had been formally declared a vital part of our planetary future at the Rio Earth Summit. Dreams are beings in their own right, he had said. But he did not tell us what the ocean had dreamed.

So I asked Mark. There was a pause as we looked at each other. It was a rainy dark December night in Santa Barbara, California. You could see palm trees outside the motel window, shrouded in sea-fog. Let’s find out, he said. You can look at the dream in five ways, I told him. You look at it in terms of your daily reality, as part of your whole life, as part of the human world, as a myth, and as a communication from the Earth. The next morning we began a dialogue about dreams that lasted ten years.

(from ‘Blue Mushroom’, 52 Flowers That Shook My World)

I am at my sea desk on the shoreline, on the last day of an Indian summer, a luminous sea stretched before me. In the marshes, the stags are roaring and the geese gathering from the far north. The ‘desk’ is in fact a bench made of a ladder, a plank and some driftwood. It’s inscribed with the words: ‘In the memory of John Meacher who built this ladder, 2013’, and is lodged under the lea of the dunes, surrounded by the final flowers of a shingle garden, tiny blue scabious, vivid pink centaury, the wind-blown ghosts of sea holly.

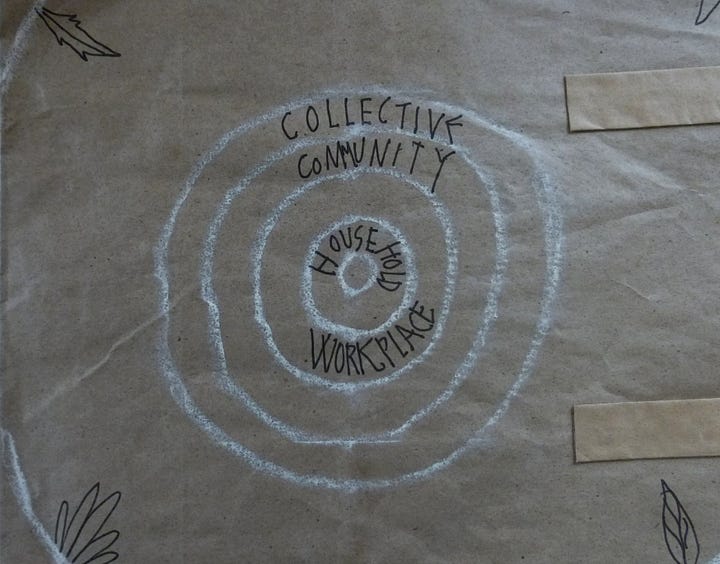

Now, I sit on a craftsman’s bench decades later asking the same question, realising it’s not the answer that matters but the asking of it that shifts your attention, and provides a metaphysical frame for any inquiry. I’ve been using those five ways of seeing as a horizontal ladder, to reach different perceptions of the world. At first to explore the language and meaning of dreams but more recently to catalyse a creative land practice with others. The levels, drawn as a series of concentric circles (see below)l act as an interface, a way of opening out engagement.

People have taken these circles to go out into the dusk, in liminal times. and capture their small journeys on paper. During the months of lockdown, to connect with the neighbourhood and collective imagination; more recently, to start up a dynamic dialogue with place, to foster relationship with its plants, creatures, weather and waterways.

At this juncture, in this third post, we are no longer in the home station of a tent in the garden, or before a mesa at a writing desk, but making contact with a territory outside the door that has called us. This territory can be any wild or feral place nearby. These circles have been practised in many places, from Alaska to Australia, in all kinds of weather; in cities and wilderness, along rivers and island coastlines, in recovering quarries and parks. Wherever you choose to explore, you need to be able to walk there, uninterrupted, for at least an hour, leaving phones or cameras behind. Direct experience is what counts.

And, as you tie your boots, thrust a notebook in your pocket, you remember: this is not personal. We do not go into the territory to seek refuge from the world, as a balm or a solace; we are going to encounter the Earth and find our place in it, to work with this land wherever we are in times of collapse. Because we know we are not going anywhere without it. That’s a different intention.

Method

These are the five levels, with basic instructions and examples of how they work from where I am writing today. You can follow the circles as they unfold. In this first sequence of ground state calibration pieces, this is about making a primary encounter with a place that will be deepened later.

Body You begin by placing yourself at the centre, grounding yourself in time and place, and then open the circles outwards. This is an embodied practice, so you need first to be immersed in your physical form: feet on the ground, heart beating, eyes and ears open, head clear of thinking.

I am in a limpid sea, between autumn equinox and Samhain, just me and a cormorant diving. It’s the kind of sea you can float in like a star fish, and feel the swell beneath you, the immensity of the sky above you, and afterwards let the sun dry your limbs. Somehow in this final exhalation of warm weather, I know that this is the last day the sea will be calm, benevolent like this, for a while. In a few days from now the temperature will drop ten degrees. I’ll be at Dunwich, feeling the menace of an undertow that presages a storm, shivering on frosty stones, the wind swung round to the North.

So this morning I am storing up for winter. I stretch out along the ladder to feel the sun’s warmth, the soft southerly breeze, red dragonflies whirling about my head; stretch out my gaze to the light glancing off the water toward the horizon; stretching out the moment for as long as I can before I have to turn back.

Biographical life The level where you consider your relationship with this place in time where it has entwined with your life.

This coastline is where I have lived for half of my life. This path to the sea through the marshes and water meadows is one I have walked for the last three years. It’s a territory where I got lost in a howling gale when I first came here, stymied by dykes and floods and ruins, but now am able to show you where the marshmallow and angelica will flower, when the cranes arrive, the sand martins depart. Where I had conversations with the people on the path, with Steve about his dun-coloured cows and how the haymaking was so late this year.

This level can come easily in a territory where there is affection, especially with the douceur of time. All its memories and stories. But when you pull away from the past, and see the land more objectively and your passage through it, you can ask: why this place? How come have I been entangled here? How, as a one-time city dweller, a traveller in deserts and mountains, have I always found myself back in these flatlands?

If you put your feet on the ground, on the geology of the place, you might find a clue: in its rock, or stone, or clay. Here on the shifting sands of East Anglia, on a bench between land and sea, there is immense space and light, a fluid base that is always changing. Somehow it is kin to my being.

Human Collective Where you expand to include everyone else and the constructed world.

When we first worked with these levels with others, the shift from the individual to the social level proved incredibly hard. This level demands you see yourself beyond your family role, the conventional identifications with your class or trade. The lack of agency is unnerving. You don’t want to see yourself as just another person caught on the wrong side of history. Already it challenges the small domestic dramas you are in, and mostly the illusion that you matter. In these times however, none of us is special. You are a consumer of resources like everyone else, part of a nation with a backstory you would rather not remember.

Suddenly this is no longer a stolen moment, a wild swim on a beach on a beautiful day. You notice the looming dome of Sizewell Power station, the wind turbines on the horizon, the oil tankers and sand dredgers. You feel under your feet the threat of the machines poised to rip up this coastline for cable lines to fuel the country’s insatiable hunger for energy. The illusionary civilisation it powers. It is a moment when the beach, with its summer memories slips away, vanishes. A terror quickens inside you.

The trick here is, of course, to hold fast. On a rocky coastline, you might have a band of limpets, a kelp forest to moor you, but here you search in the shingle for a seakale root - a root that will anchor you in a territory that moves and changes with each turn of the tide. The coast has an unsettling nature: you could be terrified of sinking into a bog, or being swept out by the tides, but its mutability also breaks up limits, frees the imagination, dissolves boundaries, allows change in. You take a deep breath. Somehow we have to live in this paradox.

Mythological What narrative are you part of? What story and myths are held in this landscape in time?

In the dreaming practice, this level explored the meaning of the dream in terms of a myth or storyline. In a walking practice, it is to see your path through the territory in mythic terms: the climbing of a magic mountain, a path through a fairy tale forest, or across a Stygian river; shapeshifting in the sea as a selkie, as a prophetic flounder caught in a net.

A writer’s work can be a crucial bridge into revealing the true nature of a place. The trick is find a text that offers a counter-narrative outside of civilisation’s capture, beyond holiday brochures and festival programmes, beyond this big East Anglian sky visiting painters have loved, its famous chroniclers of crows and falcons. Here it means looking in the marsh that is behind the bench.

Marshes and fens are places of dereliction, known for harbouring fugitives and outsiders, those who live on the edges. Here among the reeds, you might find the story: George Crabbe’s outcast Peter Grimes with a community raging against him, or a dispossessed Cap O’ Rushes, thrown out of the palace because she dared to speak the truth to her father, the king.

But there is one quieter but no less devastating writer who could visit John Meacher’s uncivic bench were he still alive. In 1994 he walked out one dog day afternoon and followed the paths that wend from Lowestoft to Bungay across the fields and down this shore. At Dunwich Heath he became lost among the heather, and had a terrifying vision of history as a labyrinth. His name was W.G. Sebald, a German professor, whose masterpiece of style and invention Rings of Saturn is a peerless example of a metaphysical journey set in a real landscape. As his narrator walks past Suffolk’s abandoned great houses and herring fishing fleet, the strange destinies of Swinburne and Chateaubriand are woven in with the gardens of Empress Tzu, the silkworm industry of Norwich, the bombing of German cities in WWII.

Once you have read this book, it is hard to sit by the window of the Sailor’s Reading Room at Southwold, the clock ticking behind you, or gaze down at the beach from the cliffs at Eastern Bavents, and not imagine his figure loping past. Reminding us of the darkness of Empire, even on a sunny day.

Earth Where you open your vision to include all the elements in the territory, all the wild creatures, the trees, air, water, stones, and see this place as an alive and communicating being in its own right, of which you are part.

The final challenge is to get beyond seeing the ‘natural world’ with your rational mind, this strip of heritage coast as an ecosystem under threat or a nature reserve. How to perceive the Earth as a live and sentient being means having a relationship with all its parts, and then seeing how those parts mesh with each other like a fabric, and become whole. This often happens when you least expect it.

On the way home, I am called to a halt: the wild Polish ponies stand motionless in the reeds, their grey and brown coats ruffled by the wind. Hello ponies, I say, and then notice their flanks and manes match the colours of the fluffy reed tassels. Oh, you are the same! Somehow, waiting there, making that connection breaks open my focused gaze, and everywhere becomes part of a pattern, a flecked tweed that is the rippling marsh, the colours of alder cones and thistle stalks, a flock of finches, the piling clouds, the sound of the invisible sea.

A heron moves slowly though the pool.

Imaginative engagement with place

There are two places in these circles, on this horizontal ladder, where it is sometimes a challenge to step onto the next rung. When exploring dreams with others, this was the shift to the social level; with territory, it is the mythological. It is easy for those with a feeling for wild places to skip along the ladder from the first personal levels to the last: to claim kinship with the Earth, to feel immersed in a fluid universe. But this is to understand a territory from a restricted view, as a fellow creature only; it won’t reveal the whole picture. To reach that kind of perception, to do this metaphysical work, you need to go through the social and the mythological first.

A full engagement means looking for a myth or story that acts as an essential bridge. Writers are outliers by their trade: famously eschewing a safe seat in society for this troublesome existentialist bench. They see beyond the gloss of a conventional narrative to the essential nature of a place, and the (often dark) memories it holds. Sebald’s study in melancholia is set in land that of itself is neither dismal, nor limited, except perhaps on the social level. Nevertheless, it shows how a walk can be entirely non-linear, interweaving fiction and dream, memoir and philosophy, shifting between times and connections to other places, a journey that is planetary as well as geographical. Saturn’s baleful influence on the text affords a structure, a way of understanding how this land – from the agricultural clay of the hinterlands to its sandy eroding coastline – can be a portal into the wider world we not only inhabit, but also inherit. How we are trapped in the gravitational pull of Saturn’s exploded moons, forces of history that repeat themselves indefinitely, caught in a ghost net of time.

Sebald’s silken thread offers no exit from his labyrinth. This is not the point of literature. But it is part of the mythos of this territory, a portal text, a way to understand the effects a waterland can have on the imagination, and a writer on a place. (Of labyrinths and exits there will be more later).

For now, the practice is about seeing in depth the places where we live and breathe. To know when you bring your attention to bear in a territory in these ways, you can see all places with an unfettered eye, so long as your physical feet are always in one place, holding fast, rooted. From here you can see this North Sea is all overfished seas, these hungry power cables, all industrial projects, these threatened woods, all forests.

Sometimes the world shifts and you see on all levels at once. And sometimes there are too many people with binoculars in the marshes. Sometime the air feels dense and fuzzy and it is hard to shake the thoughts from your head. But sometimes the door opens, the light pours through and the space expands, and you can include everything: the beauty and the ugliness, the broken and the whole, the nuclear power station and the archaic ponies, the great forests that were once here and are still here in the dreaming. So, you breathe in this sunlit memory, store it in your bones. You head home, a stone in your pocket, words already forming for the page. The wind is about to change.

Last word

Meanwhile over at Dark Mountain, we have just launched our new autumn issue Eight Fires, a all-colour ensemble exploration of the eight ceremonial fires of the year, based on our workshop series, 'How We Walk Through the Fire'. This book of practices, testimony, tools, ceremony, stories, art and poetry, was inspired by the 82 participants who went into their local territories to make an embodied connection with the more-than-human worlds in similar ways described above. We’re running a series of posts showcasing the collection over the next weeks, if you would like to dip into its pages or watch a recording of our online launch.

‘It is a book made of wild winds, seaweed shelters, glass mushrooms, talking fire sticks, singing stones, moments of joy, grief and intense physical immersion in a sentient planet. Most of all, it tells a story about re-forging an imaginative relationship with the Earth at a time of reckoning; about connecting deeply to the places we live in in a culture fraught by forgetting and isolation, and learning to find words for our encounters and acts of relinquishment and restoration.’

Here is the editorial with an instruction on How to Gather Sticks for a Fire Samhain celebration next Tuesday. Happy ancestor gatherings!

Thanks for reading everyone and hope to see you again soon.

If you would like to read further about working with the mythological level, you can find more explorations in my book After Ithaca – Journeys in Deep Time. Paid subscribers are welcome to a discounted copy if they sign up.

'it’s not the answer that matters but the asking of it that shifts your attention, and provides a metaphysical frame for any inquiry' Love this. Charlotte!