The Labyrinth and the Dancing Floor

Breaking out of modernity's mindset, finding our dancing feet on Earth

This month’s second post is rather later than usual and is unproofed, due to a recent bereavement. Do hope you will bear with me. Thanks for your understanding.

The Red Tent series began at autumn equinox and during these winter months the practice has focused on a ground state calibration, connecting with the territories where we live. As spring approaches it will now also be looking at the metaphysical work required to make a gaolbreak from the machinations of Empire, using the skills of writing and dreaming.

It’s a beautiful morning: frosted grass, a thrush singing loudly, cherry plum trees in full sail leaning out of the hedges. Life beginning again everywhere.

I have taken a deep breath and set off cycling down route 19 to Kenton Hills, Once just field and copse and hedge, the cinder track now goes past the building works for the proposed Sizewell nuclear power stations: a road, crushing pastures and barley fields, a felled wood, a drained wetland, metal fences enclosing earth and air where deer and swallows once grazed, pink flags indicating where the quarries and workers’ barracks plan to tear up and suffocate the ground. Old woodland pathways are blocked forcing me to double loop back and take other routes. Machines and hi viz jacketed men are everywhere. I’ve been putting this journey off. but at some point you have to confront what is happening in the neighbourhood, start speaking with the land. Flooded and disjointed as it now is.

‘I’d like to be elsewhere but where do you go?’ I ask. ‘This is happening everywhere. We can’t just escape.’

‘Yes, but I would like to escape,’ Shrishtee replies, and we laugh. Shrishtee Bajpai researches different forms of governance among Indigenous people whose territories are threatened by mining and other corporate captures in India and Ladakh. Nick and I are meeting her as she passes through London for a conference. We are talking about the rights of nature in our countries, how hard it is to find a common language to confront the forces of extractivism: for a people who consult the mountain spirits in everything they do and have 300 words for snow; and for a civilisation that only consults the profit margin and considers snow a logistical nuisance. How can we bridge that dissonant gap in ourselves?

Outside the almost full moon rises above Bloomsbury, a blackbird sings from the roof top. A dark-boughed winter cherry shines in the lamplight, every flower a small star. It’s a beautiful evening. Spring is coming.

You can’t escape that either.

*

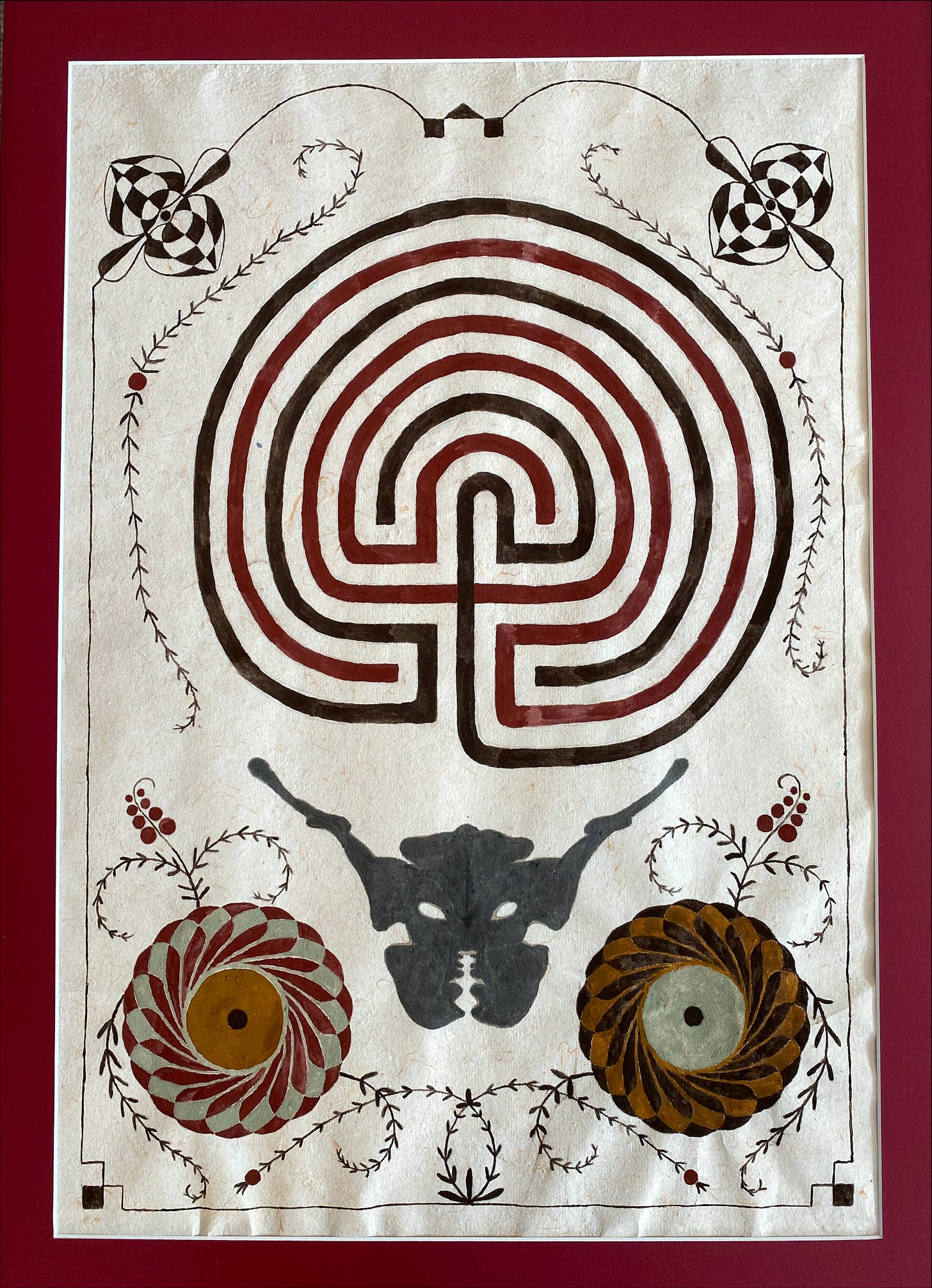

Last year I taught a course called ‘The Labyrinth and the Dancing Floor’ with Nick and Mark and Caroline. It set out to explore our kinship with the more-than-human world and remember our ancestral role as connectors and communicators within the sentient networks of Earth. With a group of 22 people we tracked the shift of the year as it reached the zenith of summer solstice. We stepped into the liminal hours of dawn, made imaginative journeys into the unknown, held dialogues with the plant world, gathered wild materials, created ceremonies and shared our Dark Mountain stories and art.

Underpinning the course was a myth from the ancient world that mapped a creative practice that might challenge the dominant mindset of modernity. It’s an essential and often joyful endeavour to relearn the many languages of Earth, but if the damaging story of progress is not unravelled within us it will constrict our every move.

And here was the rub. Everyone was happy to make a thread of stems and roots and get lost in the woods, to dream with St John’s wort and moon daisies, but not so keen, it turned out, on the dispelling work embedded in the structure of the myth. It was rough and rude, some complained afterwards, and difficult to understand. Some people on the course knew more than the teachers!

Sometimes another approach is needed.

*

I’ve been producing work based on the Cretan myth of the Labyrinth for some time now. It’s taken the form of an essay, a memoir, a performance, a teaching course and now a metaphysical practice. I use this myth as a key. Modern civilisations deliberately block access to the living intelligence of the planet and put fierce doorkeepers and troll bridge guardians to stop anyone escaping the dominance of the rational mind. The myth can be one way to unlock those doors and slip past the guards, to help break the spell of neo-liberal economics, and see the complexity of the predicament we are enmeshed in. We need to become differently configured people to live sustainably on this planet. But because myths are commonly understood as linear stories in a make-believe world their essential function is obscured: which is to serve as an imaginal container for a non-linear refit, once known as metamorphosis.

Not something you necessarily sign up for on a midsummer’s day in the West Country.

What is the Labyrinth?

First, to be clear, this is not a labyrinth you might find etched in the grass at a festival, or on a London Underground wall, or cathedral floor, a tool used for personal religious contemplation. This practice concerns the patriarchal classical Greek myth about a prison overlaid on a female-based Minoan mystery circa 1700 BC. The challenge we face is to behold the contradiction of a prison and a dancing floor existing in the same place, where all the exits are also entrances. The dualistic mind fights and rejects this kind of paradox at all turns. So, rather than escaping in this practice, we are having to ‘stay with the trouble’ (in Donna Haraway’s words, or ‘in the eye of the storm’ (in Vanessa Andreotti’s - see below) and holding the paradox. It is a deliberate (un)move to unseat the dominance of the mind.

Hard though this is, we are not on our own with this challenge. The incarceration of our awareness by civilisations has been observed throughout history, from Indigenous medicine people to medieval Gnostics to modern visionaries. The doors of perception have been deliberately closed for a long time to facilitate control. However, doors are there to be opened, as any cat or a child will tell you. You just need their formidable curiosity, and a detective’s desire to get to the bottom of things.

The Labyrinth is cleverly constructed, and it is easy to be misdirected in its many corridors and crossroads. The paths that feel like they lead to Great Knowledge or Shangri-la you find go nowhere. There are hundreds of dead ends and false passageways. You might spend your whole life searching for some kind of Narnia, only to hit the back of the cupboard. Sometimes in our hearts, in the small 3am moments, we realise this, but the ‘energy of previous investment’, our desperation to find a magical kingdom, a promised Eden, prevents us from acknowledging the fact. There is no alternative, our reason counsels us. We are surrounded by others in the same cul de sac and it’s hard to push against the crowd. Overcome by the monsters of failure and self-pity, we sulk for aeons in the dark.

Dear reader, far be it for me or anyone to deny you that position but if you want to find your way out, to release yourself from this thrall, you need to get up and do something different.

Last summer I realised I had hit a wall. There is a limit to what you can transmit in an old-fashioned classroom in an old historical house, with people keen to stay within the boundaries of the known and and not be challenged. It doesn’t invalidate the teaching, it just limits where it might fall. Sometimes, as they say, you have to teach what you most need to learn.

After the course, Mark and I went back with Caroline to her home town of Bournemouth. It was hot and midsummer, we were by the sea, and outside her flat there was a traditional rock and roll festival happening under the pine trees. After swimming and ice cream, we went there, and came across the park bandstand and people dancing wildly on a platform.

‘Oh, wow!’ I said, ‘Let’s dance!’ And leapt up.

‘I’m not dancing to that,’ said Caroline (once lead singer in a progressive rock band).

But when I turned round, she was up there too, and laughing.

‘Look,’ I shouted over the music, ‘we made it to the dancing floor!’

I hadn’t felt so liberated in a very long time.

What is the Dancing Floor?

Swallows dive and intertwine, octopuses slither around vases, dolphins play over frescos, young men leap over bulls, women with snaky locks and bare breasts gather lilies. The colours are blue, ochre, gold, white. There are no fortifications on the island, no trace of armies, or prisons.

By the time the volcano of Thera erupted, the female-based Minoan civilisation was already under threat. The dominators had moved in, rewriting the dance into a story about a hero, a princess and a monster. Half-man, half-bull, the Minotaur was kept in the centre of the Labyrinth - a prison system so complex it had even trapped its architect, the master craftsman Daedalus. Every seven years he is fed on the flesh of the young men and women sent from Athens as a sacrifice. Except one, the hero Theseus, who has been given a thread by the King of Crete’s daughter, so he can find and slay the bull-headed beast and find his way out again.

However in the Labyrinth under the labyrinth there are no heroes or princesses, monsters or sacrifices. There is instead a woman who can direct you, not through a confusing maze but into an underground spiral chamber. There is a kind of death she leads you to at the centre, but also a revelation, and then an emergence. She wears a skirt like a beehive, and a band of mushrooms around her head, she is a dancing mistress (of sorts). Her name is Ariadne.

The poet Homer tells us Daedelus made 'fair Ariadne, a dancing floor' and placed a ring of young men and women dancing on the shield of Achilles, as they emerged from a cave at spring time.

When I first came to Greece, we sailed to a small island in the Cyclades that encircle the once-sacred island of Delos. We danced. We danced in the tiny cafe, we danced at the festivals of the saints. I played a drum with Januko on his goatskin bagpipe. We danced, as people on these islands in the Aegean have done since the Bronze Age, in a circle, on a stone threshing floor on the cliff where the wind takes away the chaff.

In many ways to step into the ancient alchemical process of the Labyrinth is to undergo a threshing. You are trampled by beasts, the chaff of your life is blown away, the nourishment of the grain is revealed. Afterwards you can feed the people, you can be planted in new ground and spring alive again.

The celebration of the emerging young initiates was once called geranos, the Dance of the Cranes, and took place each spring on Delos. It was here that the hero Theseus had taken the Minoan mysteries and transferred them to the Greek god Apollo, who henceforth would be in charge of the female oracles in the ancient world. It is said that the first languages were written using the shape of the birds' feet: crane, ibis, heron.

The art and culture that follows in the hero’s dark-sailed wake however will no longer take those curly winding, colourful shapes. It becomes stiff and formalised. It loses its fluidity, it vegetal regenerative qualities; the people turn into statues, the vases turn black, the creatures become representations, objects and quarry, no longer made in delight of a co-existence with their breathing moving forms.

But you might protest, our dance halls are still full! This is true for all history but these ballroom and warehouse floors are part of the prison system. Dancing here is a hedonistic pleasure, a distraction rather than a way of keeping life going. Our bird feet are not on earth, celebrating the arrival from an underworld journey into the light of spring. There is no kiva here, no connection with the tilting sun and earth, no initiation. The young men are sacrificed and do not rise again like blades of green wheat. The women are no longer oracular, shrouded in the smoke of laurel leaves. The music transports us elsewhere, away from the Earth, not down into its metabolic mysteries.

Still some place inside us quickens, as the thrush sings in the twilight, as the golden moon rises over the field, as the distant sea rumbles in the night wind. We remember how that way of being in the world feels; and it is that inner core, how it speaks and moves the body, that this Labyrinth series addresses. To find rhythm where there is flatness, fluidity where there is constriction.

All industrial systems depend on an agreement to stay in the Labyrinth. To agree to the sacrifice of the young men and women that keeps it going. What happens when you don’t agree: when you decide not to get lost in its amusement arcades and hall of mirrors, when you flex your mind, shift your feelings, do some moves where there were none before?

The four steps

There is a start point in all dance classes known as finding your centre. Once located you are able to glide and jump and twist in the air and not fall down. The physical centre is the core of your being; the metaphysical centre is the core decision to do a work. Not to find personal salvation, or be a ‘good’ person. But because looking at the parlous state of the ‘civilised’ world, at the denial of its consequences, at the decimation of lands and people, you have to do something for life itself.

The myth here is not psychological tool but a metaphysical one: psychology can help a person adjust to a dysfunctional world but it won’t liberate us from the labyrinthine structures of family or society, the insatiable demands for princesses and monsters and sacrificed children. Using the myth as a tool for liberation however works because the Greek dominator story we have inherited is underpinned by a Minoan ceremony that is not subject to its violence or rigidity or control. Engaging in its territory shows how we might restructure ourselves with an elegance that can only come when based on the changing beauty of earth and sea and sky.

The figure of Ariadne stands at the threshold of the Labyrinth. She is holding a thread, not to redeem us but as a reminder to break out of the maze of our rational minds and to return into the flow of life. When your feet follow her spirals and lemniscates across the dancing floor, you tap into an entirely different ‘operating system’, something shaped like the ocean and the forest, like a nectar-seeking bee. Something sensual and vibrant and alive. When you feel stuck, faced with the impossible, hit the wall, want to escape but know you cannot, these four dramaturgical steps can help move you, body and soul, into a different place.

Our series over the next months will be following them. Do come and join us on the floor!

0 Finding your centre

1 Entry: Stepping away from what is known

2 Holding Fast: facing the Minotaur

3 Return: going back against the flow

4 The Dance: ensemble and celebration

SHELF

The end of modernity may not manifest primarily as economic or ecological collapse but as a global mental health crisis where the structures of modernity within us start to crumble.

Where to begin with this extraordinary book? Our labyrinth practice starts with this benchmark work because you might want to keep it by your side as a stern companion. Written by the Brazilian academic Vanessa Machado De Oliviera (Andreotti) Hospicing Modernity focusses on the mammoth task of our disinvesting from the destructive patterns of behaviour that uphold the colonial world. Every aspect of modernity is under scrutiny in these pages, alongside exercises that stretch the imagination, challenge assumptions and hone perception: from addictions to the rush of adrenaline and being culturally superior, to our childish insistence on innocence, on simple solutions, on being exceptional.

Alongside these challenges are the reworkings of the imagination, following the shapes of olive trees, ancestral mountains and hummingbirds, stories about her own struggles to reclaim an Indigenous heritage within a ‘mastery’ educational system that insists one word for snow will do. By letting the conquistador mindset collapse within our minds and bodies, she tell us, we make space for our ‘exiled capacities’ to speak for and dance with the bio-intelligence of Earth.

It’s a full on, rigorous and essential read and makes the contemporary reminder to ‘check your privilege’ feel like a kindergarden instuction. For serious dancers, this is the advanced class. As she says. No one is off the hook, ever.

COMING UP!

Meanwhile here is a call for all seafaring, sea-loving writers and artists. Last week the Dark Mountain Project launched its latest call for submissions for our 26th issue Dark Ocean. This will be a deep dive into the ‘seven seas’ of the world and explore all dimensions of the salty biome in an era of industrial plunder, from microscopic plankton to the vast oceanic currents. This book will be an uncivilised anchorage for stories and artwork that come in on the rising tides from the rock pool to the abyssal zone; made of shell and driftwood and luminescence, wind and storm and bladderwrack; tales of estuaries and lighthouses; of surfers and seafarers, slave ships and trade routes, underwater cities, myths and ceremonies, the lives of all sea creatures and ocean-roving birds. Do come aboard! Deadline:13th May 2024.

Charlotte, we have not spoken very much but the work you and Mark have done with Dark Mountain has been such a massive presence in my house and relationship. I thoroughly loved the workshops I was able to attend and the care and thoughtfulness put into them, much of that by Mark. I’m so sorry to hear of the bad news. Sending love to you with a deep sense of gratitude for the gifts you and Mark gave so generously. Blessings to you and all at DM.

Dear Charlotte

I am a very quiet follower of Dark Mountain since early days. I had access to copies of a friend who collected them. I too worked in journalism in the early 80’s. We may have shared a staircase at Nat Mags or crossed paths during London Fashion Week. I want to send my deepest deepest condolences. I am a new widow and all I can say is, treat yourself with the utmost compassion. Take all the help offered, and feel all the love coming to you. My sympathies wing through this online world to you. ❤️🌀❤️