Greetings dear readers and art lovers! Today’s post is an extract from a piece written when I first took up the role of art editor for Dark Mountain in 2013. It was an exploration, as well as an invitation to take part in our fifth and sixth editions. This is a call for submissions for Issue 28. In between these calls, I have art directed 17 books and enjoyed exchanges with hundreds of artists who have generously contributed their work. And although there are poetry- and fiction dedicated anthologies in the Dark Mountain shelves, this will be the first collection focused on visual work.

When I re-read this original call, it still rang true, because in many ways, the artists I have been working with over these years are those who hold the line for a certain way of being in this collapsing world: true to a clarity of vision, the transformative power of creativity, the love of the Earth, the material of life itself. It documents an ongoing cultural shift away from a historical perception of the world, curated by Empire towards an imaginative one, co-created with all beings who dwell here in deep time. I have substituted some of the images with artwork by this new book’s co-creators (David Ellingsen, Mat Osmond, and Caroline Ross). Do hope you can join us.

A call for uncivilised art

Those people were some kind of solution

– ‘Waiting for the Barbarians’, C.F. Cavafy

I’m exploring a territory I have not stepped into before. Maybe none of us have yet. I am not sure if aesthetic is the right word for it, but it’s the one that comes to me as I begin a new role as the art editor for the next Dark Mountain collection, as the editorial crew sift through the material for a fifth volume in a fifth uncivilised year.

Images form an intrinsic part of the Dark Mountain anthologies – photographs, paintings, drawing and illustration appear in all of them. The books themselves are beautifully and deliberately constructed; handsome hardbacks with covers the colour of damsons and field maple leaves. A physical thing you wouldn’t want to throw away. But what about the look and feel of the Dark Mountain Project that extends beyond its text? Is there an aesthetic we share as writers and artists, makers and thinkers? And if so how can we best showcase it within the pages of a book?

I wanted to talk about aesthetics in a wider context, because, even though I have long rejected the words that once earned me a good living in the city – style, design, fashion, taste – I know the look of things, their shape and form, are as important a part of a new narrative as words. The fact that civilisation holds us so tightly in its unkind embrace is not only because it controls what some call ‘industrialised storytelling’, but also because it manufactures the images that powerfully and unconsciously distract and misinform us, keep us endlessly looking at the shiny surfaces of what we feel is our cultural reality,

I want to ask: what are the arts of uncivilisation? What happens outside the gallery and the multiplex, what are the barbarian images that might liberate our vision, that bring us home? If we live in a culture that is separated from and in control of what is seen, how can we make an unofficial art created within experience to include dimensions our ordinary attention might miss? Behavioural scientists observe that change happens slowly and deliberately over time but artists know it happens in a split second: a chink in the door, a wild unexpected moment that appears before you and for no reason you change lanes. A flash of quicksilver that can transform the dark materials of a whole culture.

When I walked through the trees at the Uncivilisation Festival, past sticks arranged in a circle on the ground, people in animal masks, slates hanging from the boughs of a tree, I recognised something that made sense of a long journey I had once made.

A coyote on a television looking across a valley, a hare leaping inside a poem, Rima Staines’ Weed Wife covered in flowers on a sheet of oak, Dougie Strang’s Charnel House for Roadkill, like an archaic Tardis on the steps of the Glasgow Art Gallery.

Uncivilising the eye

I have to tell you a story about that journey. Because that’s where this exploration begins.

Late ’80s,walking down Bond Street, my eye is caught by a room full of vast chunks of stone and a pale suit hanging on the wall –an Anthony D’Offay exhibition of Joseph Beuys’ The End of the Twentieth Century. The stones are hewn from basalt, a stone that will form Beuys’ perhaps most famous work, the planting of 7,000 oaks in the city of Kassel in Germany. The suit is made of felt, the material the artist tells us he was wrapped in by nomads when his Luftwaffe plane crashed in the snowy wastes of Crimea. Felt and fat saved his life, but they also transformed his life. They became the materials that defined his art. On a video Beuys is telling the world: in the future everyman will be king.

I could say this was the moment I walked out of galleries and stopped writing copy about Bond Street. Because shortly afterwards I left the city whose high culture I had been steeped in for 35 years. The change happens quickly but it sometimes takes years to thrive in the world without those beautiful clever things that shielded and once defined you.

Roland Barthes in his elegant deconstruction of the bourgeois mindset, Mythologies, laments how hard it is to forge a culture unbound from a market economy. John Berger in Ways of Seeing show us why: pointing to a painting of a Dutch interior where a wealthy burgher sits surrounded by his possessions – his library, bolts of cloths, furniture. Shipped from all round the world, the goods set a pattern for material desire that has become the stuff of Sunday colour supplements ever since.

This is the art of civilisation. Globalised goods, fetishisation, possession. This is mine, all mine! Houses, horses, naked women, rich and poor, the painter who paints the canvas and the canvas itself. And even when art has rebelled against the pattern in a hundred dexterous and avant-garde moves the painting (or sculpture, or drawing) is still possessed. It is still property, a commodity in the minds and hands of those who could buy it – once the Church and then the collector and the State museum.

What do art and aesthetics look like within the frame of collapse? What does photography look like that is not alienated from its subject? How do we love the world in a time of extinction?

What do art and aesthetics look like within the frame of collapse? What does photography look like that is not alienated from its subject? How do we love the world in a time of extinction? I look at my own collapse in order to see what that might mean. Because although I was educated in the dominant culture, there were strains of an uncivilised aesthetic that ran counter to everything I was taught, flowing dangerously beneath the surface like the river Styx. I wrote about the one perfect gleaming designer chair but my eye was always caught by rougher stuff that felt it had content and not just form. Like a linguist in search of a lost language, I would sometimes stumble upon its broken vocabulary.

A circle of driftwood in Derek Jarman’s garden, a spiral of stones on a table at Kettles Yard, a path that led through the tundra, walked by Richard Long.

These were the creative salvage years in London where makers like Tom Binns conjured ‘unjewelry’ from keys he found in the Thames foreshore or sea glass from his native Donegal; where welders like Tom Dixon made furniture from scrap metal. Post-punk warehouse years before corporate style had taken hold, when the original cut of your coat, or tribal marking distinguished you. There were chinks everywhere if you looked.

One of those chinks I went through in Bond Street and found myself in Mexico. To liberate yourself from the mindset, you sometimes have to leave the city that bore you, or crash into another territory entirely.

Finding the chink

In Mexico I did not go to museums or churches. I watched market squares and mountains, the colours and the vernacular of places. Later I looked at plants and at dreams. For six years I stopped writing and taking photographs, took out a notebook and studied living forms and the shapes of my imagination. I was uncivilising my eyes: shifting my attention, away from an aesthetic moulded by the hard lines of Balenciaga and Mondrian and Diane Arbus. I learned not to be enticed by the siren images, the fairy world of haute couture and Hollywood.

I learned to wait in the long American afternoons, for the slow and deep and resonant thing to appear.

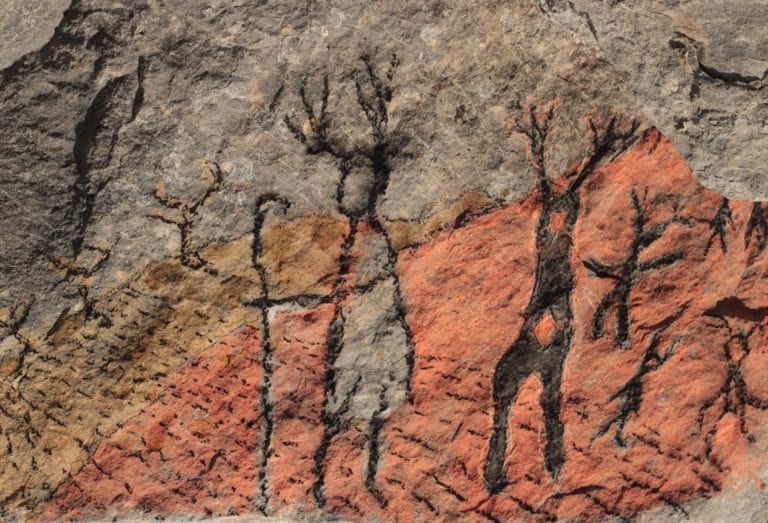

It was as if I had never paid attention before to the world. These glimpses became the main track: images that were archaic and aboriginal, that spoke of trees and elements and beasts and weather, that linked the people to the dreaming of the planet. The rough beauty of the woodcut, the mythic fairytale, rock and cave painting, the shapes that follow the contours of the earth. The art that invites us to engage and remember, rather than possess and to forget. To ask questions rather than feel superior with our great knowledge of paintings and history.

From them I learned that the ancestors do not look like the gods. That barbarians do not speak in perfect prose. All artists wait for Prometheus to arrive with his firebrand to lighten a darkened world.

Although I did not go to exhibitions in these years, I met artists. I met sculptors and painters who lived in Bogota and the Arizona desert. I met the Slovenian performance artist, Marko Modic, on his way back north from Tierra del Fuego where he had travelled alone with a dog and a camera. Marko was an extreme caver and mountaineer and he brought that wildness and strangeness into every room he entered. And that’s when I realised that the buying and showing was not the true function of art. It was the practice of the artist themselves: their capacity to live against the grain, the shape they made, the line they took.

From them I learned that the ancestors do not look like the gods. That barbarians do not speak in perfect prose. All artists wait for Prometheus to arrive with his firebrand to lighten a darkened world. The best of them know that time is a gift, not a curse, and that waiting is part of the art. That all paths lead inevitably away from Rome.

The artist is the one who can find the chink in the door and allow us to push it open. In a fixed and atrophied world they act as strange attractors bringing chaos and freedom and new life. Their work and their practice break dimensions in time and space, throw wild seeds into monocultures. In a disconnected world they bring connection. And sometimes they bring us back.

Following the track of the coyote

There is a moment of return and that too comes as a surprise.

I am in the Museum of East Anglian Life, at an event called What if . . . . the seas keep rising? As the director of the new economics forum and a woman advisor from Natural England talk about climate change and what this might mean to the marshlands and coastline of Suffolk, there is a photograph on the wall that has transfixed me.

It’s by the sculptor, Laurence Edwards. Two men with long poles are taking clay giants on a raft down the river Ore. These are the Creek Men, the beings of these waterlands that have emerged from the landscape, from the artist’s imagination and from his hands. I can’t stop looking at that image. Like an anchor among a babble of voices that I will not remember, it was an image of belonging that made sense of everything.

I realise now what grabbed me was something that Mexico taught me years ago. At some point the ancestors return and reclaim the earth. All civilisations which ignore their original blueprint live out the consequences of that defection. And whether you understand ‘the ancestors’ as the primordial forces that govern this planet, or a part of yourself that makes sense of everything, to which you are loyal in spite of your upbringing, they are always here: we just have to see and feel them. Make space for them in paper and stone, in a corner of our tidy lives.

In that journey I understood that artists are the ones that remember the tracks those ancestors made in the beginning. Those shapes and colours appear in dreams and on canvas, and artists follow them, in the cities and on the seashore, walking across the land, reminding all of us who watch them of the way back. And when the rational world seems to make less and less sense, becomes more and more incoherent, so it is that the artists come with their intelligence and their wit, their delicate brushstrokes, the rivermud under their fingernails, their masks and their surprise to push the door.

Taking part

If this book were to be an exhibition, it would be a Dark Mountain retrospective, a catalogue of the many genres we have published over the years: photography, illustration, graphic literature, calligraphy, painting, sculpture, land-based artworks, making, installation and performance, with texts that explore all of them and the creative frame in which they are made.

If you would like to take part, we are now open for submission of short pitches for texts about uncivilised art (200 words max), These suggestions can be for essays, stories, creative non-fiction, monographs, practices and interviews from short caption stories to full length pieces (up to 4K words). They can be philosophic, political, poetic, placing attention on specific artworks, artists or projects, or wide-ranging – on different genres, or the role of art in a time of collapse, Sample images to go with the pitches are welcome.

Please note: we won’t be accepting poetry, or CV-type ‘artist statements’ or artworks on their own. Many thanks all!

Please look at the submission guidelines for details and fill in this form if you would like to contribute.

Deadline is 15th April, 2025. Many thanks all!

Thank you Charlotte! Your writing slows me down, and I return again to read. Re Beuys I don't think anyone recovers after being exposed (to his peculiar light), I explored his work in landscape school, and was delighted to see Beuys' Multiples at LACMA Los Angeles in 2010. Unfortunately photos were verboten.

Somewhere along the way since I heard that when the oaks were young the basalt columns helped keep them alive through dry periods - either through holding water themselves, or holding water around their bases - still scouring my notes to find the reference - but it may have come from a gardener I met who came from Kassel.

I spent over a decade of my life wondering why I did not go through the door and walk into the halls of the Ivy League to do the “artists” life. Over twenty years later with the world collapsing around us, it’s clear to me that turning away was a gift. This is the thing.

So many lines in this I wish were part of my own artist statement, so many of these line I need to paint above my door and never forget, because it’s so easy to forget and think the way home is to Rome. Thank your beautiful soul Charlotte.

“…Because although I was educated in the dominant culture, there were strains of an uncivilised aesthetic that ran counter to everything I was taught, flowing dangerously beneath the surface like the river Styx…

…To ask questions rather than feel superior with our great knowledge of paintings and history…

…It was the practice of the artist themselves: their capacity to live against the grain, the shape they made, the line they took…

…The best of them know that time is a gift, not a curse, and that waiting is part of the art. That all paths lead inevitably away from Rome…”