ancestor

on exile and the bitter medicine of an ancient plant

Today, we are launching a Substack for Dark Mountain’s online edition and you can take a peek at its intro here. To celebrate its launch, I am posting the piece I submitted to their third issue: a chapter from a book I was shaping up at the time, 52 Flowers That Shook My World. It’s about the ancient desert plant, creosote, sometimes known as chaparral, and what happens when you are forced to leave a place that feels like home.

In our recent issue Mary Dohnal wrote: ‘Be prepared to lose everything twice in your life’. If Mark was one of those heartbreak losses, this records the other: an exile from the high desert where we once lived in the borderlands between Arizona and Mexico. In the wake of recent events in the US, this farewell is perhaps prophetic as the world closes its borders.

creosote

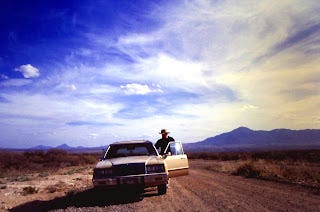

Swan Road, Arizona 2001

I have a jar I keep in a wooden box in my room, and sometimes I take the jar out of the box and open it. As I do, an extraordinary scent permeates the room. It is a smell like no other, a scent that takes you, heart, body and soul to a red land, to the great Chihuahua desert after the rains. It takes you deep into the heartland of the chaparral, where the bitter-leaved, scaly-limbed, golden-flowered bush that emanates this perfume grows: the creosote bush.

The creosote is a formidable bush, known as la gobernadora because it inhibits the growth of all plants that grow around it and thus can command great areas. The bush is commonly called by the same name as its habitat: chaparral. But it is also secretly known as la gobernadora because when you step within its territory you know it is the plant that is in charge, with whose authority you do not quibble. As a physical medicine, its tough leathery leaves can heal almost anything. The chaparral’s medicine lies in its slow combustion. As it takes hold of a territory the bush slows the combustion of everything around and thus inhibits the germination of other seeds. Its inhibiting nature has the same effect on alien organisms within the human body, and also works within its own form. It is an ancient plant that lives for a very, very long time indeed. There are stands of creosote that have been carbon-dated to thirteen thousand years. La Gobernadora is in charge because she has a formidable memory.

Mimi once told me that a sprig of creosote brought a woman she knew back from the brink of death. Memory can do that. And perhaps that is why I am here in Swan Road today, sitting by the creosote and digging my hands in the red earth, so I can remember everything. I breathe the warm air under a blue sky that already bears the tinge of winter. If god had meant you to be in America you would be American, we were told when we came back from Mexico. I sat beside the bush and thought of these people who had been here for a hundred years at the most, and wondered what gave them such authority.

At some point the moment you never want to pass comes to pass: you have wondered about this moment. How would you respond? This is the moment, I thought, as I walked into the immigration interrogation room at Phoenix airport. This is the moment you come to face the man that god has put in charge. The man in the uniform with the pale face, in this room without windows. In a bad time you don’t get out of this room: you get your liver torn out. On the border of the bad times you get your visa torn in half. You get to be called an alien and told to pack your bags.

I sit in front of the pale man and look at him directly. He has all the power in this moment. He can put me on a plane, or not, and he toys with this power, as a cat will toy with a mouse. He is the good cop. Mark got the bad cop. He got a Mexican woman called Rose screaming at him on and off for two hours. This man is smooth talking, reasonable. I resist succumbing to the relief, the feeling of being let off the hook. I follow the interrogation, point by point, answer the questions, and consider my options. I feel like opening my mouth and yelling, but something is being held in balance. Our fate is yet not decided. There is a small space, a possibility and I want that possibility. I want to have enough time to say goodbye.

‘What are you doing in the United States?’

‘I am a writer.’

The pale man laughs. He holds our travelling book in his hand. It was published in 1994, he tells me, as if to discount the fact, and asks me again what I am doing returning to Arizona?

‘I am writing a book about plants.’

‘What is it about Arizona?’

‘I love the desert,’ I say. ‘And I have friends here. This is a B2 multiple-entry visa. What exactly is wrong?’

‘You have done nothing wrong,’ he tells me. ‘You have to go back to your country, buy a house, get a job and be normal.’

‘I already have a job, I’m a writer.’

The man is not listening. He does not live in a world where people are writers or consider wild plants, or return to places they love. He is filling in forms. I am a person of no consequence. An alien like all aliens. Not American. Not normal. Of no use to the Empire. Soon the form will be completed.

I wait and watch his every move.

‘One day you can write about this,’ he tells me.

I look at him and at his name plate which says Richard.

‘Not about here, of course,’ he adds hurriedly.

‘You mean in Phoenix, Arizona?’ I ask.

I wanted to say it was not paradise, this place I come back to. It was not a land of milk and honey, a god’s domain of easy living and garden flowers. It was a territory of wild, bright spaces, mountains and sky. A place of thorns and rattlesnakes, where you could speak with people who thought there was more to this mysterious life than getting a job and a house and being normal. It was not paradise, but it was a place in which you could feel alive.

It was not hell either. But sometimes you could feel an antagonism between the people and see chain gangs working along the highway. When the wind blew from the south the sulphuric acid from the copper mine slag heaps stung your eyes and often, when you sat down by the devil’s claw or the soaptree yucca or any of the plants that grew abundantly along the border, the patrol would stop and demand to see your passports. You are making us nervous, they would say, and wanted you to stop looking at flowers and go away. It felt like everyone wanted everyone to go away, even though there was space everywhere you looked. You woke up and there were helicopters at dawn, searching for drug runners and refugees. You would find young men standing in the garden, lost and collapsing with thirst and exhaustion, looking for shelter. It was not hell, but it was a warrior land where you were challenged each day to be alive.

This is the moment. Do you have the courage in this moment to surrender?

You could yell, cry, shout about injustice, your innocence, take a haughty stance, threaten. But you don’t. Something inhibits you. Instead you grow slow and still and watch. You realise that in this room your independence, your integrity, your creativity, which you value above all things, have no value. In this moment you have no power, but you have memory. You know that beyond this room, beyond the history of men and mines, of native wars and border patrol, there is another Arizona. There is a bush that commands the badlands that can take all your ills away. It is unremarkable; you could pass it by as you drive along the highway. La Gobernadora is older than god, the god of the pale-faced Americans and all the other gods of the world. She is older than all these conflicts, older than this grief, older than all the aliens. She sits like a cat, perfectly contained in the heart of the red desert, and keeps her own counsel. In a bad time, you go to her.

La Gobernadora is older than god, the god of the pale-faced Americans and all the other gods of the world

When we finally arrive back in the desert in the dead of night, the tribe of cats will come where I lie in the straw bale house and surround me. All night their soft bodies will purr against mine and keep me warm. The constellations will turn above us. At times I will awake trembling and find one of them looking at me with her deep mysterious eyes. I will hear their sound in the darkness and fall back to sleep. By morning, I will awake and know what to do.

What you want in a difficult time is to act like a warrior. You want to be impeccable. I want to say goodbye in the few days now granted by my surrender. You can come back in six months, everyone told me: the lawyer, the state department, the man in the windowless room.

I can come back in six months, I told myself, but part of me knew I would not. A door was closing. Bad times lay ahead.

We gave away everything we had collected over the years: books, thriftstore clothes, pots and pans, a wicker chair, the car. We sat with Mimi in the round house and poured the six Snake Sequence essences into bottles and packed them in boxes. We closed our post office box, visited people, swept the paths. In the cool mornings we sat under the cottonwood tree, under the elder and the mesquite. We sat on the roof and watched the sun come up with the cats sitting beside us.

We sat overlooking the sky islands, San Jose, the Mule Mountains, the washes, and gulches where the medicine plants grew, all the speaking bushes that were silent and dark in the early light. And then on the last day I went to Swan Road.

Swan Road is a place we loved to go. Down a small dirt track off the road to the Junction there was a patch of ground where we used to sit as evening came, especially after the rains when it had become lush. There was a ring of the speaking bushes I had made essences with – ocotillo, desert broom, creosote – and you could sit by them and see around the great rim of the San Jose mountains, and yet feel sheltered from the vastness of the flatlands. It was a sort of desert room.

The quail would come running in and out of the dry wash, talking to each other; ravens glided overhead croaking. It was a peaceful place and rarely disturbed by the border patrol. Now, after the monsoon, it was carpeted with marigolds and purple flowering datura; the devil’s claw flowers had turned into green horned seed pods, the creosote flowers grown into fluffy grey seeds that caught the rays of the sun.

Last time I had come here I had brought a confused girl called Meneka who had blown into Bisbee, into our lives, briefly, like a tumbleweed. She had found an injured cat in the road, but couldn’t pay for its treatment at the vets. She was afraid the cat would die. So we gathered mud from underneath the creosote bushes for a wound pack.

I knew creosote could cure almost any kind of desperation, so long as you spoke with the plant. Mimi had told a dying woman: go to the plant that speaks to you. The woman picked a tiny twig of creosote and it sparked new life in her. If you have courage, the creosote will speak to you of things that can overcome the greatest of shocks. To be refused entry to the land I had loved for twenty-two years was, at that time, the most shocking thing that could have happened.

‘Now you have nothing to lose,’ said the creosote quietly as I waited beneath her scaly arms, her seeds like small paws held in the breeze.

I waited by the bush for a long time in silence. And then a great sob broke from me as my heart broke open. I realised I would not be coming back. You are an alien. Alien as the young men from El Salvador I had once harboured in the desert garden, alien as the Mexican man and woman I had given a lift to in our car. We were all aliens, the people of the Earth who came to live here. Our forms were stamped, our eyes were lasered, our fingerprints in files, in documents, on computers. I felt my broken heart open: it broke out across the land to include everyone that had been driven from it. It stretched back over the line of immigrants who were crossing the border. It stretched back past the train that had stopped in the middle of the desert in 1917 and thrown out all the striking copper mine workers, over the Apache nation hunted and driven out of these mountains until Geronimo surrendered in 1886. People driven out, made homeless, put on trains, planes, deportees, evacuees, refugees, torn up from their roots. In this heart-breaking moment, I knew what it is to be in exile from a place you love.

‘Now you know,’ said the creosote. ‘Will you be strong enough, is your heart big enough, to contain the bitterness of this world?’

In that moment I knew there is nothing worse than not belonging to the Earth, to be exiled from its beauty and its mysteriousness, unconnected to its power to drive away all ills, its medicine, to its long root, stretching back through time, anchoring us in a time and space in which everything can be seen and known and treasured for what it truly is.

‘Who is in charge?’ asked la gobernadora.

‘You are.’

‘We are,’ she corrected me. ‘Where do you want to be?’

‘I want to be with you,’ I said.

‘You are always with me,’ she said, ‘because you are me. And now you can go.’

I poured the mother essence into the red earth, embraced the bush, and bid Swan Road farewell. I got into my desert-coloured car and drove back to Turtle Ranch. I did not look back.

The medicine of the creosote is bitter. Bitter, like all the heart plants. Only a heart that is bitter knows how to feel beyond its personal circumstance, to reach out for its fellows. A time when you have nothing to lose is the time when life opens up. When you are terrified of losing, you close down and do not see the bigger picture; you care only for yourself, your space, your desert. When you are terrified of losing you do not see that things that you counted on were not to be counted on, that friends, community, one’s own talent or good nature, would not prevent this now-imminent banishment. It was a kind of innocence that went then. Creosote is a sobering bush:

I knew that had circumstances been different, had it been a different time and place in history, I would have boarded a train that led all the way to the gulag and no one would have been able to stop it. In the speaking bush years at the beginning of the millennium, the taste in my mouth was the taste of bitterness. Once you have learned to live with the bitterness of the heart, you take this medicine everywhere you go. It is the bitterness of the heart that will cleanse the world of all its grief and history, just so long as your heart can still love. So long as you can still sing your swan song, a song of everything you once loved and had to say goodbye to, and if you can remember the scent of the desert after the rains long after you have left it, and most of all, if you can remember who is really in charge.

There is a jar that sits in my room in a wooden box and today I have taken it out. Seven years have gone by since I distilled these leaves and flowers, and in this space of time many rains have fallen on the desert lands where these bushes grow, but I have not been there to see them. No one I once knew in the old mining town by the red hill is with me any more. But the plants are still with me, and I only have to remember and I am once again on the red hills running past the bearberry, sitting beside the wild flowering lilac, turning the bend at Swan Road. In the world beyond history there is an Arizona where we are always welcome. And in my long creosote memory, in the long count of my life, in my land-dreaming capacity, I can see that people always come and go, but the plants always remain. I can see that when the human dramas fade, when my heart recovers, what is left are the speaking bushes of the desert. What is left is Turtle Island. What is left are these words in my mouth, these rain-washed, bitter-scented words.

You can read more about the Speaking Bushes of the high desert in our book about plants, 52 Flowers That Shook My World: a Radical Return to Earth.

This is a very moving piece of writing. Thank you, Charlotte. Thank you, la gobenadora. In this time of breaking, may we be healed and deeply, may we be re-membered by the land.

Chaparral, Coyote Brush, Ceanothus…as an old biologist/ranger, I resonate.