In my last post I wrote about the mythical blacksmith Wayland and how he was trapped in an unkind servitude. This one is about the bird he became to free himself. And about May, which is the time of birds here in England, as the green world springs towards the sky. And the singing. The songs we sing in the dark times.

Just before I interviewed Derrick Jensen in London, I went to the woods to visit the lilies-of-the-valley, which lie carpeted below a giant beech in a place they call Sizewell Belts. It is a stretch of mixed woodland and meadow pasture that Derrick might deride as a ‘beauty strip’, a line of trees that habitually hides the reality of a clear-cut forest in his native California. Because behind this leafy strip, once a full-bodied wood and fen, beyond the intoxicating scent of these flowers, lies the devastation the building of a nuclear power station is wreaking on the land, a road and railway that rip across the fields, leaving razed hedges, tree stumps and concrete in their wake. Dead creatures lie on the sides of roads, driven out of their underground and brushwpp shelters. Hare, fox, badger, deer, mouse. 21,000 trees destroyed at the last count.

I wanted to get in touch with the sustained fury that comes through two decades of the eco-philosopher’s writing about the industrial killing of the planet. so I would know what questions I could ask him. To know myself what to do when you live on the frontline, a place where, as a chainsaw cuts down another oak, further down the road, you hear a nightingale singing in full daylight among the wild cherries.

hawk

Derrick Jensen is not so much a bird as a bear. We had been sitting next to each other, leaning in to speak into my antediluvian tape recorder (a relic from the 80s) which made his ruthless logic about extractivism feel even more urgent. He is about to give a talk titled ‘In Defence of Wild Nature’ which he has been touring with in Europe with his collaborator, Lierre Keith. His advice in the face of increasing destruction of the land: find something you love and protect it. All resistance requires a network of people. Do what you are good at.

Afterwards we walk into Red Lion Square and I introduce him to the London plane. High in the canopy above us a wren was singing, and that’s when I remember standing by a strong-armed bush know as bearberry on a red hill overlooking the vast Chihuahuan desert. I had just arrived in Arizona, and was trying to find my bearings with our project, The Earth Dreaming Bank. For days, it seemed the land and the plants, the trees, the rocks, were entirely silent. But this bush was definitely speaking with me. Above us, soared a red-tailed hawk and I found myself flying with him and seeing the land in all directions. Suddenly I knew I was in this place for a reason.

The bush was asking me a question: what are you going to do about the American dream?

Lark

Three people with strimmers, razing the flowers in the ditches by a barley field where larks are building their nests.

Why are you cutting down trees in nesting season?

‘ We are cutting down the undergrowth, so the birds can’t nest there.’

What? Larks are ground nesting birds.

We are hoping they will go to the next field.

What? That one which you have paved over and emptied?

We are maintaining the property.

Where is this road going ?

We don’t know. We are just doing what we are told to do.

Raven

There was a game we once played with people. It went like this. What was the first role you ever acted? Whatever you remembered, that was the role you would play in your life.

‘I don’t remember,’ I said, ‘which one came first: the angel Gabriel or the Wicked Witch of the West’. I remember desiring the angelic wings that hung all year in the art department of the church hall school I went to, and how when I was ten I could finally put the harness on and sing a carol to assuage the mighty dread that had seized the troubled minds of the shepherds. But, until that moment, I had forgotten my other dramatic entrance: when I flew into the ballroom of the Dorchester Hotel, cackling and cursing, in what I thought was a seriously scary manner and the audience burst into gales of laughter. I was mortified. They had taken me as a fool!

‘What was yours?’ I asked Mark. ‘I was supposed to play one of the Wise Men,’ he said, ‘but then I was ill and couldn’t take part. So my first performance was a mime. I played a bird singing in a cage, and then freeing itself.’

We both laughed. The story of our lives, I said. Here, we are with our great metaphysical practices: but no one can hear you and everyone thinks I am a clown.

Robin

He appeared after Mark died. I heard a flutter of wings. And there he was, bold as brass, stealing the cat’s food. He had flown through the bathroom window. Pretty much every day since then he comes on his larder raid, and sometimes brings his mate. Robins are famously friendly with human beings, and you only have to hold out your hand with sunflower seeds and he will hop on and take a few. Or if I am digging the vegetable parch, he will come and sing in the goat willow and then swoop down for any worms I might have unearthed.

What always struck me is that the bird of England is not a fearsome raptor, an eagle or owl, but this small bold song bird with a red breast. You think that to change the course of things, to be effective, you need to be a big creature with talons and a fierce beak, a powerful dominator with a crowd of supporters behind you, but sometimes you just need to be the one who is not afraid to be a fool, or to go where you not supposed to go. Sometimes, as I stand by the sink, I hear the robin’s tap tap tap as he hops on the kitchen floor, and my heart leaps.

That’s what writing can do, what artists can do in a place. You think you are alone but the sudden appearance of birds – a soar of house martins above the May Fire, a murmuration of starlings over the roof, a burst of nightingale song in spring – tells you otherwise. People loved Mark because when he appeared he reminded them of their hearts, kept silent in a world driven by the violence of the will. They felt cherished. If each of us have a song this was perhaps his: the heart will prevail if we cherish the Earth, come what may.

One night I dreamed I came up the stairs and a small bird flew out of his room and into mine. He was by the window, and I opened it, so he could fly free.

This is my own (though it sounds more like a caw): may all beings find their wings and liberate themselves. This is the place where break out happens.

Tap, tap, tap.

Curlew

1 ONCA Gallery, Brighton, Sussex

‘How amazing you know the land where the curlew lives,’ the young participant said. We were gathered on the gallery floor around a model of the bird’s wing and were decorating it in different colours. Normally mightily resistant to craft making, I found myself nevertheless joining in, marking the rim of the wing with the curlew’s habitat grasses from the pile of pens in front of us. Outside a wild Westerly wind was roaring. It looked like the ritual burning of the paper bird on the beach to mark the end of this pioneering art collective might be postponed. In the session we were mourning the extinction of the slender-billed curlew, and a young women was sobbing, as we spoke out our grief about what we were all losing in the maw of industrial capitalism.

It struck me then that some of the people in the room had never heard the haunting cry of a curlew, in spite of living near its Sussex stronghold. And that there was something not quite right about those tears. Was this lament what the bird, the Earth, needed from us?

2 Havergate Island, Alde river, Suffolk

It was silent in the hide. The people were focused looking out across the water towards, all manner of wading birds, ducks and geese: shining water and domes of mud, dotted with curved beaks, stilt legs, graphic plumage, a medley of sounds arising. All the wildness and beauty of the winged world. I normally I just watch the shapes of the land in a hide, but I have borrowed Camilla’s binoculars and I am finding all manner of species I recognise from guide books – widgeon! greenshank! grey plover! – and calling out their names with excitement, which I am sure is not good form in bird-watching company.

Occasionally, the birders do point out a bird they have just spotted (‘curlew at one o’clock’). It is a quiet affair. But when I tell my fellow island voyager about what is happening to the nesting birds in our hedgerows, to the larks in the fields, there is a loud murmur of dissent, as one by one the birders denounce the work of the nuclear site. They know all the facts and figures and have been resisting the build, standing by the birds for decades.

You think you are alone, that the silence of ordinary people is consent. But then you voice something out loud, and realise you are really not.

3 The Scallop, Aldeburgh beach

Sand Martin, Oyster Catcher, Avocet, Shrike Shearwater, Sedge Warbler Bittern strike!

‘What is your intent for the dream?’ asked Henry. There were three of us gathered around the fire bowl as the light drained from the sky. It was the end of a week of warm blue days, and now the clouds were gathering, and a sharp North wind run up the beach.

‘What is the Ocean dreaming now?’ I said. It was the question that began our dreaming practice years ago on the Pacifica coast of California.. I’d like to know in this time of so much destruction, what to say, how the sea can help us and we it. What we discovered in the practice was that when you tell your dream out loud, when we speak or sing for a place with our physical voices, other beings in the place can hear us. Our silence is not consent.

Henry has invited us to sleep on the beach before the initial event of the Beach of Dreams project he is part of. There are hundreds of small flagpoles poles embedded in the shingle, representing 850 miles of the UK coastline and over 100 upcoming community events this month, celebrating its beauty and its challenges, as we face an uncertain future. We have brought our sleeping bags to spend the night sheltered under the lee of The Scallop, a metal sculpture on the beach at the edge of town.

The sculpture is a broken shell of steel, created as a tribute to the Suffolk composer Benjamin Britten by the artist Maggi Hambling, and a place to reflect on the power of the sea to affect human imagination. Carved out across its skyward rim is a line from his most well-known opera, Peter Grimes:

I hear those voices that will not be drowned

At dawn, just as the warblers strike up in the marshland behind us, Henry asks: ‘Are you OK, Charlotte?’ Are you OK, Camilla?’ Yes, I say, as we lie together listening to the darkling sea against the shingle. A soft breeze runs across my face. Something has shifted. All the glaring lights and coldness have gone, people are quietly moving around us, placing the coloured silk pennants in the poles, getting into position as a five-part chorus to call up the sun.

If I could dream

Just like the sea

If I could breathe

Just like the sea I am not much of a night dreamer anymore. After years of untangling the epic dramas of our dreams in the practice, prising open their layers to find their riches, from the personal to the mythological, my attention is now on the deeper dreaming of places, and our presence within them. One thing I know about dreaming: you have to wait until something reveals itself, and only a creative act can make sense of the assemblage of elements you find in your hands: A parliament of birds. A choir of voices.

My first encounter with this beach was when I was a Hesse student at the festival created by the composer and his lifelong partner and collaborator, the tenor Peter Pears. Britten’s music is embedded in this coast and he famously invited its community choirs to take part. For years, the haunting interludes of his Aldeburgh-set opera called me back to this shore. And although, I sold my cello many years ago, and no longer listen to classical music, the coastal town remained in my heart. And maybe this is why I am lying here under the shell, trying to find a harmonic in the face of discord, a convergence I can hold between my life here, a lineage of people who love this shore, and the North Sea itself.

I don’t know what do about the American dream, which is the dream of most people trapped in industrial civilisation. The dream allows you to use the Earth like an amusement park, to consume all its riches, without taking any responsibility for your presence in a place, or your forebears’. When I flew up with the hawk, the land revealed itself as a living intelligent force, and that finding its language was my task as a dreamer and scribe. The bearberry asked where my allegiance lay: I had replied, the Earth. When I had to come back to England, it was these dunes that invited me to stay. In these years living by this sea, I have learned that to speak with a territory, the relationships you make, need to be stronger than the twinkling lights of the Ferris wheels and merry-go-rounds of this culture, the illusions powered by their insatiable demand for energy.

I wanted to know what to do when your landbase is torn up in front of your eyes by people who do not see it, or care for it, or you. I know to be caught up in rage and powerlessness only fuels that violence further, and how easy it is to cry tears that are not just yours. My intent in these posts has been to communicate what what I have learned: to show how loving a place, being allied with it, can be our best chance at withstanding collapse. From Mark, I learned that the heart will prevail if we let it, because it is not alone, it speaks to all beings and it lives in time. It can be at home on the Earth, which the restless unsatisfied dream of civilisation will never let you be.

I was aware we were marking something by our sleeping beneath the shell, and that its meaning might not be grasped straightaway. One thing was clear, the night was not harmonious,: there were no stars, only artificial lights flaring across the pebbles and the horizon - the trawler and dredger lights, the glare of the nuclear power station, the streetlamps of the town, the headlamps of cars, the head torch of the security guard, checking the poles each hour. But by dawn the singers had arrived to greet the sunrise. And somehow their arrival changed everything, the way something shifts when someone asks if you are OK because it matters we are all OK.

The words for ‘The Song of the Dawn to Dusk’1 were gathered on large pieces of paper in St Peter’s church hall a month ago. We walked carrying the coloured pennants across the curlew’s territory behind the town and then wrote our memories of the sea, and our distress of what was happening in our heartland.

The choir are now singing them: they are singing the soft sounds of the sea against the shingle, and the relentless human battering of this land and ocean:

Casting, Catching,

Grasping, Snatching,

Hooking, hauling,

Trapping, Trawling,

Wheeling, Winding,

Pounding, Grinding,

Diggers clawing

Concrete, pouring

And they are singing of the birds and the flowers that make their home here.

Curlew and Kittiwake, Sea Kale, Thrift, Yellow-horned Poppy and Hornwrack drift.

It’s International Dawn Chorus Day. It’s Mark’s birthday. He would have been 63.

I stand on the ridge of the rising sea kales and throw my hands up towards the sun that now bursts through the clouds.

‘Happy birthday Mark!’ I shout, as a ribbon of light shines across the dark water.

Thanks for reading everyone! Next Monday I will be giving a class on the transformative learning platform Advaya called ‘Myth, Knowledge and the Dreaming of the Earth’, as part of a creative ecology course. Do come along. You can join me for the webinar here.

All quotes are from ‘The Song of Dawn to Dusk’, compiled and set to music by Kirsty Logan with The Rabble Chorus

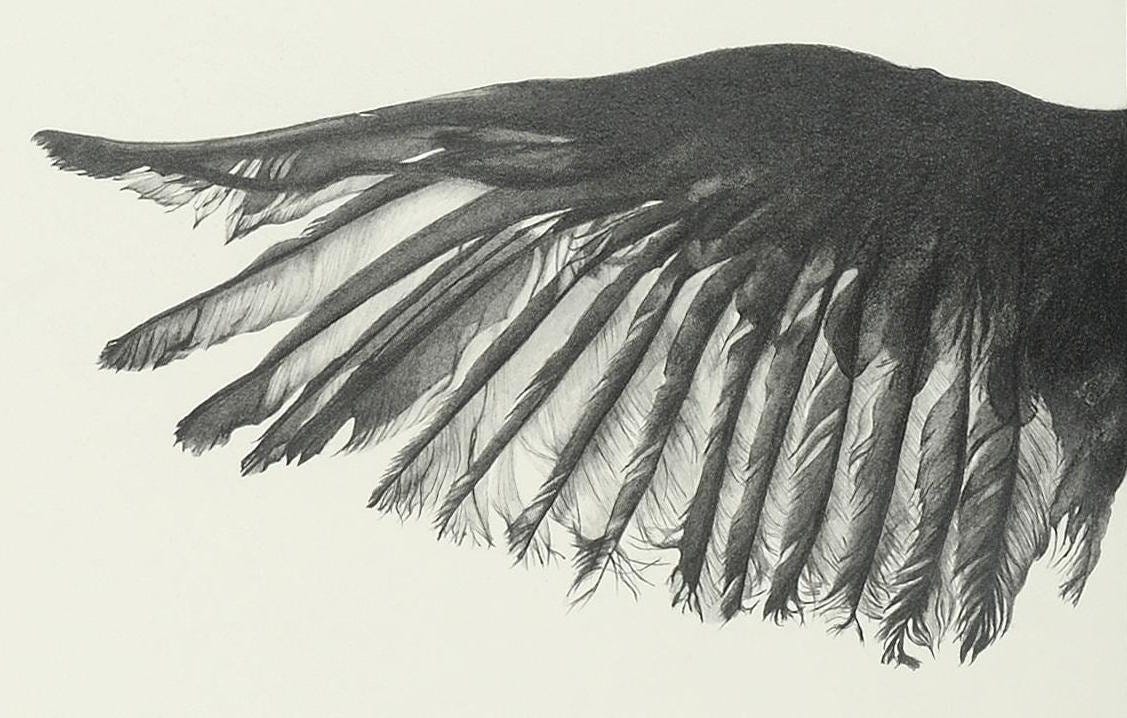

Hi charlotte Your thoughtful post, and Rebecca Clark's drawing brought to mind Hannsjörg Voth 1940-, a land-artist/sculptor who has made a series of very personal dreamlike (and somewhat temporal) spaces in the Moroccan desert, engaging with local craftspeople. I never met Hannsjörg, discovering him in the late 90s, but his approach and vision (esp. re time) influenced how I think, and conceptualise. Rebecca's drawing made me think of the third image here; https://doorofperception.com/2013/07/hannsjoerg-voth/ an Icarus wings sculpture he hand-forged for Himmelstreppe (Sky stairway), 1985.

Really loved this one. Admittedly it might be partly to do with the subject matter.