Whenever we think of home we come to this:

the handful of birds and plants we know by name

– John Burnside,‘ Ports’

Before solstice. Walking across the hayfield with Carrie on midsummer eve, waist high in brindled flowerig grasses, an almost full moon rising, a barn owl flashing past the oak, a chorus of blackcaps and thrushes singing in the hedgerows. The air is warm and golden and still as a pond. Tomorrow we will jump over a fire, greet the sun as it rises over the rippled sea at Dunwich. At the zenith, at twilight, this small corner of England appears as rounded and brimming and magical, as Samuel Palmer and his fellow Ancients once beheld the Kentish countryside, and felt they had inherited paradise.

After solstice On Lowestoft beach at the First Light Festival, I am watching a play in a white tent called ‘Phoenix Dodo Butterfly’. The play, centred within the climate and ecological crisis, places three characters on an imaginary farm on the Norfolk Broads and shows three post-flood scenarios: total collapse of the food system; a mitigated collapse; and the regeneration of the land and its ecology. I am there as a ‘responder’, taking part in an audience discussion about how we might face the future, how we might rekindle our relationships with the wild and arable plants, with the land and each other. Outside the band plays and the flags ripple in the breeze and the children run into the shiny sea. It’s a struggle to hold attention.

Plants are our lifeforce. We know rationally we can’t live without them, nor can the insects, or creatures, or birds; that everything depends on them, for air, food, shelter, but we live in an industrial civilisation that gives this kingdom no heed, except its use as fuel for our bodies, or cars, or as decoration in our houses and gardens. No matter how loudly the band plays however doesn’t hide the feeling that everyone is suffering the consequences of this dismissal in chronic ways: physically, emotionally, mentally, personally, politically. If we want to live in a ‘butterfly’ future where our homelands can start regenerating, it matters how we see these fields in the hinterland as portals to paradise or purgatory.

It is easy to say to a festival audience, ‘we need to move from control to relationship, from our heads to our hearts’, but the core metaphysical Red Tent question is: how do you make that complex move from monoculture to diversity on the inside as well as the outside? How can we reconfigure our perception of an Earth, so that the plants become central to human culture in a way once understood by our ancestors and by our future-looking flowerminds1?

Plant knowledge

In June I promised a leafy introduction to the plant practice, but there are many different paths across these fields: I could take you along the margins where the wild roses and mallows bloom, inside the field where the barley shivers like the coat of an animal. Or pass through the shadow of the power stations where vipers bugloss and pyramid orchids suddenly gleam, and the sea peas extend their arms like green octopi. Or we could walk down the avenue of small-leaved limes on one of these hot summer days, listening to the bees roar in the treetops, and pick a pocketful of lime flowers for a sweet-scented tea before sleep. All of these paths can lead towards kinship, regeneration, beauty, resilience, so it is hard to know where to begin - or end.

I could start at the beginning of the practice in 1999 when Mark and I struck out to Port Meadow in Oxford to investigate the common dandelion: how we decided to pay attention to the ‘weeds’ that grew outside our back door, a year when the wild and feral plants of the waste grounds, botanical gardens and towpaths became our teachers and collaborators. But then, preparing a post for Dark Mountain’s Plant Practice series, I chanced upon a ‘postcard from the edge’ I once wrote for a community writing project, about living in the desert. I realised that to outline the practice as it has now become, a teaching, I had gave some of the background: its original inquiry, its medicine attention. Intent and frame is everything in a practice.

Because no matter how assiduously you study plants, an immersion in a wild territory, where ancestor knowledge is still held in the soil and the rocks, is what really counts. When Mark and I went to Bisbee, Arizona and learned plants the hard and beautiful way: by loving a place, and then losing it.

Medicine People (1994-2001)

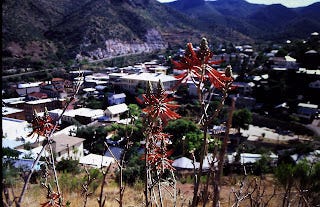

The sky island rises above the desert floor; a ring of mountains known as The Mules. The town within its rocky arms appears, at first glance, unremarkable: a collection of small wooden shacks scattered up a red hillside, down a gulch, with narrow steep streets, skinny metal staircases, a red-bricked main street with a few old-fashioned storefronts; an alternative cafe, a co-op store, a library with oak floors, a parking lot shaded with ash trees and desert willow. By the highway that winds through the mountains there is a ‘hell’s hole’ where European immigrants once mined for copper; in the abandoned gardens the fruit trees they planted still grow - pomegranates, mulberries, figs. Everyone that lives here has been somebody somewhere else. One day they woke up in the city and the desert called them. They got sick, or cried too much, or had a dream, or like me, met someone on a film set who said it was funky place full of artists, full of thorny attitude.

There is something that calls you: in the luminous space that surrounds the border town, in the mineral mountains, in the prickliness of the people. Something that brings you to be tempered in the alchemical furnace of the desert. To gaze up at the stars that burn bright in the obsidian sky. Outside the thorn bush and cactus keep their independent positions in the flat lands and in the canyons. Keep your distance! they say to each other with their formidable spines. Stay out of my way! And yet standing amongst them you have never felt so together in your life.

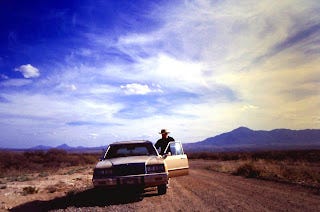

For seven years 1994 - 2001 I came with Mark to this old mining town in the Chihuahua desert. We rented apartments, bought thrift store furniture and made friends with those fierce independent spiky people. This is a postcard and if I could put everything I loved about this place into it I would. But that’s for a book.

What I want to say is I learned a lot of things here I couldn't have done if I'd stayed in my conventional London life. England is a time place, cold and damp and saturated with ghosts and history, obsessed with form, always looking back. Arizona is hot and dry. It's all about space and opportunity and looking forward. My old friend Carol went into the desert when she was 40 years old. Everyone had left her and she had to start again. She sat down in the middle of nowhere and cried for a long time. Then she put her hands into the earth and her hands formed bricks out of the red mud. She built a house with those adobe bricks and then she lived there.

To start again you have to find a new point of departure. I had left the city and my old life and I had to learn another way and this is where I learned it. I learned medicine plants, I learned to live in a straw bale house without A/C or a telephone or a lock on the door. I learned to hold my own and come to my own conclusions about the empire, as I watched chain gangs working along the highway, when the sulphuric acid from the mine’s slag heaps stung my eyes, when I heard immigrant families running down the streets at dawn and helicopters searching for them, when found young men standing in the garden, lost and collapsing with thirst and exhaustion, having walked and hitched all the way from El Salvador.

I learned from real hippies who had settled here in the 70s: flower girls who had come out of Haight Ashbury, artists who had walked away from fame in New York, who had spent ten years travelling in a bus across America, radical lesbians, activists, poets, the first permaculturists, the first people to build compost toilets and grow organic vegetables. People who had put themselves on the line and weren't going back. They were tough and bitter when I met them, living in rooms full of books with painted floorboards and a wood stove. And I spent winter and summers in those rooms in an old miner’s hotel, in an adobe roundhouse, in a yurt. I lived among medicine plants on the edge of the wild desert and I listened to their stories. They passed everything on. Everything that worked and everything that didn’t.

It was not paradise. It was an immense red land with an immense blue sky, where you could drive out down a road edged with sunflowers all the way down into Mexico and feel entirely free. But, of course, no one was entirely free. ‘Little roads not immune from grief,’ Carmen used to call them. This was Apache territory, the last tribe on Turtle Island to stand against the white invaders. They lived in warrior bands in these sky islands like mountain lions, red bands tied around their heads, men and women smoking the rough leaves of wild tobacco.

What I learned from Arizona was about keeping a flame of a different world alive in spite of circumstances. How you do this without losing heart. How to endure alongside the earth and all its creatures. How to withstand the shocks of history and keep your humanity intact. To live a medicine life. How to wait in the long afternoons, to live without comfort or convenience. How to walk through the territory and not be afraid of snakes and scorpions, of flash floods or a bear or the border patrol asking you, what are you doing out here? How to look them in the eye and say:

Why officer I'm looking at a flower, what are you doing?

I'm looking at this scrawny stick because underground it has a vast reservoir stored in its tap root that can keep it going through this summer drought and tonight when we are sleeping it will unfold its white lotus-like flowers as it does once a year. And all the moths in the desert will be summoned by its extraordinary fragrance. I'm learning to be like that flower that some call Queen of the Night and the Apache call Pain in the Heart.

When I returned to England I brought that medicine with me. It's a bitter medicine because it's got broken heart in there and shattered illusions, dreams that didn't work out and loss. But the medicine of the heart is bitter, because it's our experience that will really come to matter in Transition. Not just our obvious skills and abilities, but those some of us learned while we were out travelling in the far-flung places, on the road, waiting in a desert town for destiny to knock on the door.

Working in the field

If Oxford was our plant undergraduate time, and Arizona where we undertook field work for our masters, surely the most difficult part of the journey was working in ‘real life’. It is a hard re-entry, endured by all students and practitioners, the moment when you are thrown out of an intense hermetic study into the indifference of a mundane world, into a culture where your intelligence and experience count for nothing.

However when we settled in Suffolk on return from travelling we knew that the plant practice had to relate to what was happening in our ordinary lives. It had to make sense within this territory of agricultural devastation and feudal relationships, of living in a conventional village where, even after 20 years, we would never ‘fit in’, the way we once had in an alternative Oxford or Arizona.

Here, surrounded by beet and barley, by poppies and poplar trees, we explored all the plants of the neighbourhood and tried to find ways to make our presence and work relevant within the human collective. One day, I found myself taking on a weekly wild plant display in the local museum. I had been talking animatedly about sheep’s bit scabious at a party, when Pam Ellis, a formidable mycologist who had been running the show for 25 years, accosted me. Wary, but also intrigued, I agreed with the proviso I could write a small paper to go alongside the jam jars that sat on the sunny windowsill. I was unashamedly enthusiastic. I hadn’t had a ‘readership’ for over 10 years at this point and was thrilled to have a deadline again (writers!).

One week I wrote about the 18th century poet (and amateur botanist) of the saltmarsh and fens, George Crabbe, now mostly only known for his dramatic poem about the outsider fisherman Peter Grimes in the ‘The Borough’, and the central tragic figure of Benjamin Britten’s eponymous opera.

I went in search of all the plants in Crabbe’s poems and particularly the tiny inverted clovers which he loved: burrowing, reversing, clustering, suffocating, hiding themselves away from human tread in the sandy soil, as many of his poetic characters do. On my knees, I found myself glimpsing sparks of light and colour and beauty among the tiny pea flowers, myriad other worlds within this one:

You feel the enormity of being alive, of so many possibilities, as if you could begin again, yet the human world is so old, so repressive, how can you shine in your own right? How can the future begin?

You might not want to look closely like this, but somehow you have to. You have to think of Crabbe as he stands exuberant in the primordial fen, downtrodden and despised in his various curacies. You have to consider yourself, squashing your knowledge and breadth of vision for a new world into these small cards on a windowsill. You want like all writers to share this knowledge, your love of the natural world, have an intelligent and lively conversation with your peers, but the old forms will not let you. Hemmed in by taxonomy, by a restricted imagination, by minds trained to dismiss the wild and the beautiful, you can get no further than a smile. You are clever to know the Latin names, the women will say down at the museum and look away. Nature table, says the guide to the local museums of England.

- from ‘Suffocated Clover’ (one of the unpublished chapters from 52 Flowers)

What broke our isolation and brought back that sense of a future and possibility was joining the then-burgeoning Transition movement, when we became communicators and event coordinators within a lively group of community activists in the market town of Bungay. Within Transition’s frame of preparing for an ‘energy descent’, knowing what was happening in the arable fields and along their wild and vibrant edges found a use. Our plant work and practice of ‘making ourselves at home’ suddenly made sense, not just to ourselves but to others.

Mark led his first neighbourhood plant walk around Marsh Lane in 2009, introducing everyone to the local ‘spring tonic’ plants: nettle, cleavers and dandelion. We gave a small slide show about the practice in our cottage, and afterwards all made green teas and nettle soup and ate together in the garden. It felt like the beginning of a new and joyous time. I started to write a book about our practice, a collection of monographs, travelogue and memoir, that would become 52 Flowers That Shook My World.

We had discovered a bridge.

PART TWO: ‘Store’, the second of these Plant Practice posts, will follow at Lughnasadh (August 1st-2nd) with a piece about harvest, plant dialogues, butterflies, and how the flowers of the dog days help navigate descent.

METHOD

Here is the ‘tech’ we used for all our investigative plant work, including when we worked with others in many different terrains. It comes from a Dark Mountain piece written by Mark and is taken from his teaching work.

TUNING IN TO PLANTS AND TREES

So what might a plant practice look like and what do plants have to say to us? It starts with a decision to make time and space to go out and sit with them and pay attention; to open up, listen at depth, and engage in a two-way dialogue.

You can do this exercise alone, although I find it works better with a partner or a small group (up to four people). If you’re with others, you can work with the same plant or different ones, whichever you (or the plants) decide.

There are three parts to this technique: first you go out to visit the plant or tree in the land you are in (making sure you go beyond your garden to somewhere that is not under your aegis or control). Then you return home and revisit the event in your imagination. Thirdly you put the experience into a creative form, a piece of writing, a drawing, even a dance or song. The whole process can take several hours, so give yourself enough time with no other distractions.

The visit

In the territory you are working with, go out and find a wild plant or tree you resonate with or feel a pull towards. If you don’t know what it is, don’t worry about identifying it – some of the deepest connections with plants can happen before you know what their names are – and resist any temptation to take photographs. The initial experience should be a direct connection between you and the plant and not be mediated by tech. You can photograph and identify the plant at a later time if necessary.

A gentle word of advice here: touch the plant only if you know for certain it is not poisonous and you feel invited to do so. Treated with respect, poisonous plants can turn out to be the best of teachers and companions, but you don’t want to be handling them or putting them in your mouth!

Sit down next to the plant and greet it as a fellow inhabitant of the place. Take a few deep breaths and focus your awareness on your feet until you can feel them tingle. Then become aware of the surroundings that you and the plant/tree are within and a part of. The season, the air, any sounds. Take notice of everything that’s happening.

Get a sense of what the plant’s intelligence might be and what it might be relaying to you. Let yourself become conscious that plants are aware of you as much as you are of them. You are not alone. Let your awareness expand into the surroundings and feel how much life is around you. Notice how your body is responding. Your feelings. If your mind gets distracted with interfering thoughts or a desire to get up or escape, bring yourself back with gentle deep breaths and sit with it, including (especially!) any discomfort.

Stay for at least 25 and up to 40 minutes, then thank the plant or tree (‘Great to meet you’ works well) before you head back home.

I call this process sitting down alongside with, as it gives a sense of both you and the plant as fellow planetary beings within the territory.

Revisiting the plant or tree in your imagination (visioning)

Find a quiet place indoors to lie down and relax with no distractions. Close your eyes, take some deep breaths and revisit the experience with the plant in your imagination. Be open to what emerges without judging and trying to get anything right. Be aware of any messages or ‘medicine’ the plant may be relaying to you – these may come in the form of physical sensations or memories, or be verbal, visual or on a feeling level. The plants can even reveal themselves as ‘human’, animal or in other forms, and they can also be very humorous. After 20 minutes or so, thank the plant and bring yourself back to the room.

Follow up and creative work

After the session, take notes and/or make drawings. If you are working with others, take turns to give testimony to your experiences and listen to each other (see the earlier post Encounter on the tech of speaking circles for a way to engage in this).

Over the next few days, pay attention to any dreams where the plant might appear. Visit the plant again, and identify it if need be. Immerse yourself in the whole experience. Connecting with plants in this way can have an impact much beyond the actual time you spend doing the exercise.

(from ‘How to Hang out with Plants’, Dark Mountain: Issue 24 -Eight Fires)

Thanks for reading everyone and hope you have wonderful flower encounters this summer. See you soon!

Flowermind was first mentioned in my valediction post about Mark, ‘Bridge’: ‘The writer Tom Robbins once wrote that the next epoch would be ‘The Age of Flowers’. Human beings, he said, posses three kinds of brain: the reptile, the mammal – the midbrain – and the flower-powered neocortex. In the Age of Flowers the ancient fight between the mammal and dinosaur brains would cede to the visionary leadership of the neocortex. The neocortex fits like a swimming cap over our heads and receives its impulses and information directly from the sun. All inspiration happens in this part of our brain. I used to imagine it like a flowery swimming cap women used to wear in the ’60s. Certain flowers lighting up certain parts of our minds.’