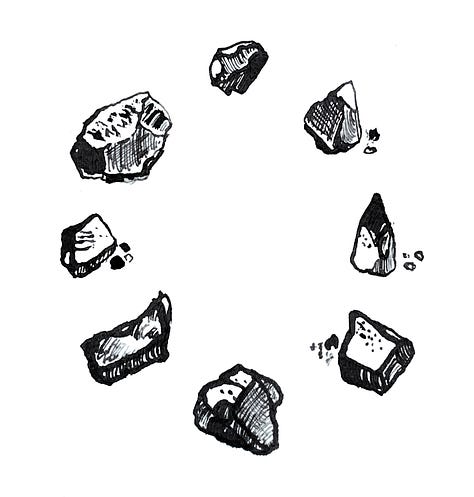

The idea was simple: we would build a cultural practice together that could weather the storm of converging crises using the ‘stone clock’ of the equinoxes and solstices and the four stations of the growing year, known by their Celtic names: Imbolc, Beltane (or May Day), Lughnasadh, and Samhain.

We met as an assemblage of human beings, raised in the ruins of late capitalism, who exchanged their engagements with places, framed by an ancient calendar that asks different things of us as people. To listen to the polyphony of each other’s voices as a way of breaking out of the monologue of modernity.

from We Walk Through the Fire, editorial for Dark Mountain: Issue 24 – Eight Fires

The track through the woods is muddy, rutted after the long rains, but today the sky is a brilliant winter blue. I swing up into the arms of an oak, watching the afternoon sun slant through the rusty bracken. In my pocket there are eight stones. The stones mark the eight spokes of a clock, a clock that has been in use for thousands of years since Neolithic times, marking the turns and twists of the solar year.

These eight stones have taken bands of people up hills, into moors and forests. We have sat with the land in these crossover times, and afterwards spoken about our dialogues with the Earth together in small circles, hosting fires to celebrate our gatherings with storytelling and song.

In other places, people have take up positions around the clock, and spoken from their different stations. Two young students in a Denmark classroom sit alongside each other either side of the summer solstice. One has a smile, full of promise and light; I am sad, says the other, as I feel the summer is disappearing. Two men, who have lived together for many years, sigh in the workshop tent in a Reading park as they find themselves unexpectedly in the moment of Samhain.

The stone clock tells the time: not 24/7 mechanical time, but the time of the Earth and our embodied lives, when we feel its tug, like an underground river under our feet, when we turn to the one we know and see their face, furrowed like an oak tree. We realise that the youth of the world will not return, and wonder how we can bear the loss of things if death does not also signal a beginning. The year is fading, quickly in the cities, slowly in the woods. You go into the territory to makes sense of time, witness its transience and poignancy. Those oak leaves that only a week ago flamed bronze and copper beside the gold-tipped spruces, are now extinguished into brown. The conifers take fantastical shapes in the dusk.

After lockdown, the stone clock land gatherings became a year of online workshops, where people went into their home territories and brought back their encounters, shaped in story or image. Showed the assembled company how they walked into the fierce winds of spring, or immersed themselves in the wild waters of high summer, how they lit their May Day and equinox fires. This month, in four sessions surrounding the winter solstice, we are looking at what lies beneath our feet as we step out: the dormant seeds, the edges of twilight, the dreaming of beasts. What might root us in a collective practice for the year ahead.

The river Minsmere has broken its banks, flooding the marshes and meadows, and the road that leads from the woods back into Eastbridge. I wade across the freezing water in my bare feet, too-short gumboots in my hands. Halfway through I stop. I’ve walked over this bridge hundreds of times but never entered the river. The water feels alive. There are eels that come here every year, their migration only marked by the village’s mysterious pub sign: The Eel’s Foot. Staring into its reedy dark waters, you would never know they were there. And yet walking through, you feel a presence, an otherness, you would not notice by ordinary sight. Rio abajo rio. The river that flows below the river, where these mythical creatures, who have swum from the far Sargasso Sea, come to spawn as they have done for millions of years. The water holds the memory.

Our body holds the memory. The ancestral bones within our soft animal forms. In the classes we stand up, feel our feet, feel our hearts beating, as we breathe deep and sense the wind and frost, our hands that once imprinted cave walls in ochre and clay, hands that recognise trees by touch, collect bark and feather and stone. When we meet we speak of our encounters as if around a fire, telling stories under the stars. Beneath the fire another meeting is taking place, as we listen, aligning ourselves to the movements of the Earth and sun in a civilisation dangerously out of kilter. We find this dissonance inside us hard to name, and yet feel it, as we hold the door open for another year to begin.

The eight fires of the stone clock act as markers in time and space, and demand two kinds of attention we have called ‘ceilidh’ and ‘kiva’: the joyous poetry, song and dance of the Celtic gatherings and the sober mood of the ceremonial underground chambers of the south-west pueblo people. You need both to attend a fire, the lightness and the depth. This depth is hard to access in company, unless you share a practice, an intent to weather the shift of attention that takes you down. Our task as guides is to hold it.

In the session, people share stories about getting lost, in the snow, in the desert, in the forest, at sea. We listen for connections. In all the accounts, after the panic and confusion subsides, something else kicks in. There is a shift of gear, of tempo. The fear gives way to excitement, awareness, intuition, connection, the feeling that the mountain and the river are alive and communicating. When you step off the marked trail, the Earth can speak with you; you realise there are other paths to explore, in the woods, in your imagination. On the tarmac, all roads lead to Rome.

You are lost according to the maps of civilisation, but find your feet here on the planet. Nervous of speaking out loud in a hostile human world, you find your voice in the kiva.

Breaking the husk

In the kivas on the mesas of northern Arizona, winter solstice marks the pattern of the year ahead – the kernels of corn from each house are stacked on an altar, feathers and pinyon needles hang from the rafters. In these underground chambers, a ceremonial struggle is enacted as the sun is persuaded to return, to nourish the seeds and then the people. Afterwards up above in the plaza there are dances and celebration.

Each seed holds the past and the future within it. Held mute in our civilised cocoons, we need a force from the outside to break us out of our restriction, germinating the seeds of the future we hold inside of us. Our husks are broken open by storm, by a gentle rain, by the teeth of creatures. But some of us are cracked open by a fire that scorches us awake. However the germination comes, it feels like the end of something old and a beginning of something new.

We are not born into a kiva culture, our ancestral practices were banished long ago by religions and empire, except in rural places where the seasonal struggles between light and dark are still enacted in the streets. But somehow our bones know this process, our archaic bodies with their modern hyperspeed brains, cross-wired to only pick up the broadcasts civilisation wants us to hear. How do we break out of this constriction and see the planet as it really is?

Somehow we have to immerse ourselves in a different time. Walk out, collect sticks for a solstice fire, hold vigil, watch the sun rise. In the gap between the end and the beginning, we let our carapaces break, liberate our ancestor roots to secure us in earth, free our future selves to shoot toward the sun.

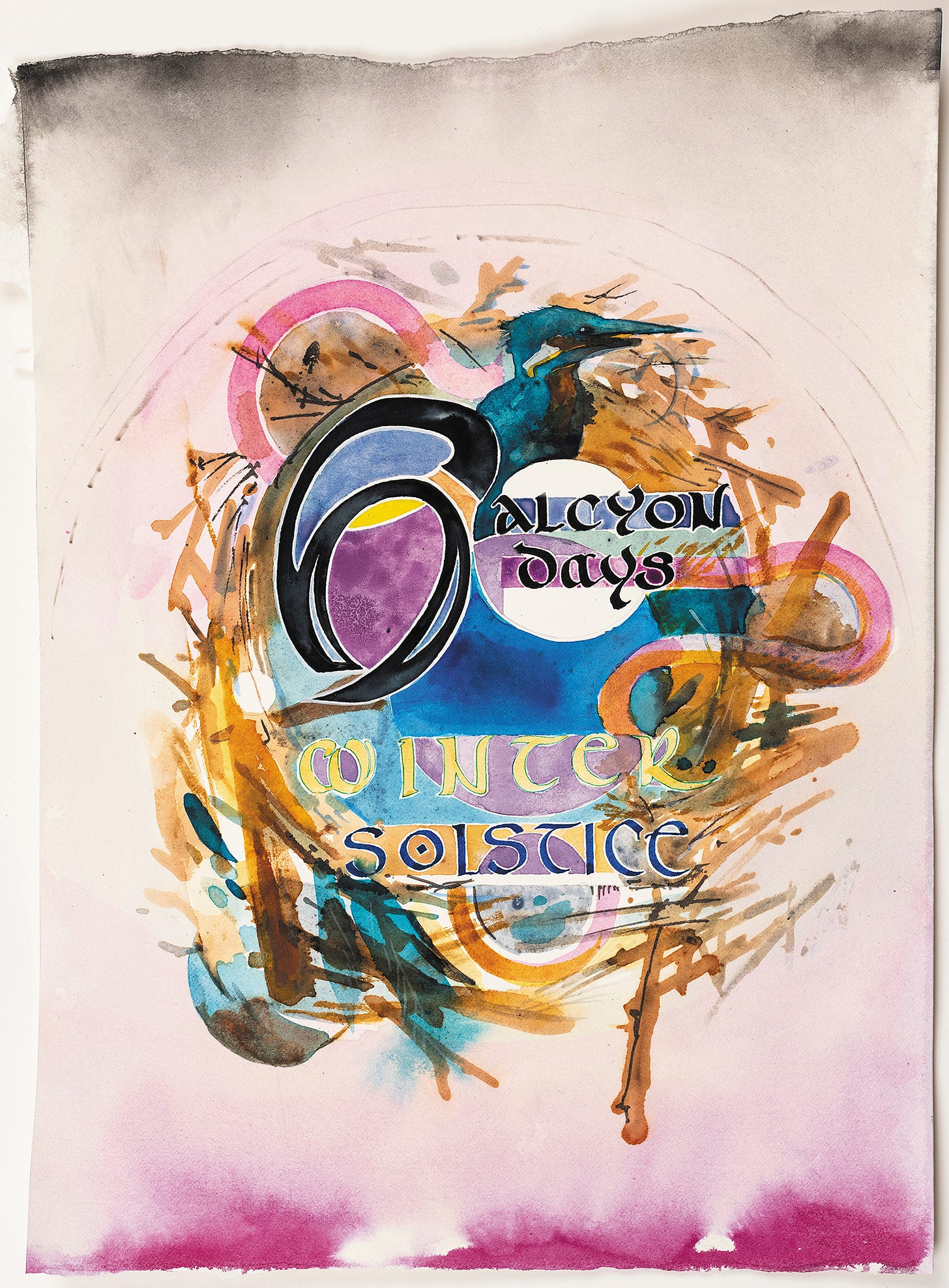

Halcyon Days

There’s a strange shape floating on the sea. It’s round and twiggy, and you can’t work it out. And the sea is calm, which is also puzzling. Shouldn’t it be rough after these winter gales? But before you can answer, a tiny jewelled bird flashes past, and lands there, and you see this shape is a nest, and the bird is a kingfisher. She is sitting on this boat-nest which has one egg in the centre. And before your rational mind says. this can’t be a kingfisher which you know full well harbours her clutch of eggs in a riverbank, you see a body of man lying in the sand washed up by a storm.

All this time, however, your fact-fixated mind hasn’t uttered a word, because the story has compelled your attention, forming a bridge into your imagination where river birds can build nests on the sea. I’m telling the story backwards of course but the riddle told the right way round reveals the key elements of the myth, its kernel. The kingfisher was once a girl called Alcyone and the man is her beloved husband who was drowned in a winter storm at sea. The lovers had angered the gods, who in a rare moment of remorse turned them into kingfishers, Every year now Alcyone’s father, Aeolus, commander of the eight winds, calms the sea, so she can build her sea-girt nest in peace.

It’s a love story, a shape-shifting story, and an ancient Greek myth full of jealous gods and rainbow messengers, revenge and transformation. But it’s also a life-death-life mystery, forged in the fire of winter solstice: a paradox that sits at the heart of creative endeavour, an old drowning year and a new one incubating under the coppery breast of a tiny water bird. We have angered the gods, but for a short while the waves have been placated. The new can be reborn. So long as we can find the time.

The Halcyon Days are the kingfisher days, seven either side of the winter solstice. In these sessions, in this pause, we are each building a nest, a space of quiet, to hone a creative work set within our territories. In its centre, we will build a fire, and hold the space between one door closing and another opening.

Aboriginal academic, Tyson Yunkaporta in his superb book of instruction, Sand Talk - How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World (see Shelf below) writes about the reclaiming of our ‘ancestor mind’ that can happen when you put intense focus on a creative, ceremonial task. A high level of concentration repairs that connective part of the mind that has fallen into disuse, This ‘extra-cognitive’ faculty is the part of our intelligence and intuition that allows us to read and touch the Earth. Keen and lively in ‘undomesticated humans’ and children, it is systematically blunted by education and given no quarter in the civilised world.

Still we yearn to live on a planet that speaks to us, where we can feel part of its living fabric. To recover that state, we have to sift through the ruins of civilisation for clues. We need to find the myths and tools that can still forge bridges across the dimensions, and not tarry by the merriness of the ceilidh fire. The stone clock determines when you go down into the dark dramaturgical space of the kiva. In that attendance, you allow the alchemical forces to struggle with the old and the new within you. You experience the utter black night, the dead of winter, and you call the sun back.

Without a marker in time, it is easy to lose yourself: you can be swept away, hostage to the tides, to the marching bands of history. Down by the beach, the long shore drift of the North Sea drags you along the coast without your noticing. I leave a bright coloured towel on the shingle as a marker and swim against the current. It’s hard to get back to where you are camped. And also comedic. You swim and appear not to be moving. I’m not going anywhere! you shout. But then, laughing, you push yourself, and you get there.

That self-amusement, that effort, is what it takes.

Augury

I went to the beach to listen to the deep roar of the sea on the shingle. to prepare for the week’s winter session. I lay under a clear sky, thinking about the myth of Alcyone, and remembered how on another calm day, swimming at sunrise, a bird flew past me, skimming the waves in all the colours of the rainbow: a kingfisher on the sea! No, said my mind, it can’t be. And yet, there it was. A flash of utterly magical colour. It was a bee eater, a rare migrant from Europe. looking for a place to nest in the East Anglian sand dunes.

Sometimes you go out and the extraordinary happens: you just have to be open and vulnerable enough to let it in. Sometimes you need to create a hermetic space: a nest or red tent, a shift made by attending a fire, walking slowly at twilight, entering a place where things are not certain or fixed. A time when you dislodge yourself from clock time, holding a stone from an ancient calendar in your hand. These Halcyon Days, like all days around the eight fires, are times when the gulf between dimensions becomes ‘thin’, and the other creatures and beings of the neighbourhood can communicate with you in their own language, of appearance, or song, or colour.

For many years, we used to go to a neighbourhood oak to wait for the winter solstice sun to rise, and even when we couldn’t see it in the sky, a hare would appear, a flight of jackdaws tear past, and the day would suddenly lighten and break. Sometimes, in a hard time, we would go to the oak to steady ourselves, and a word would tumble into our minds, seemingly out of the blue. After sitting at its roots, hearing the wind in the leaves, the small birds above us, gazing across the barley or beets in the field, any difficulty we were undergoing would somehow resolve itself. Later those oblique words would make complete sense. Visiting the sentinel oak at the crossroads, marker of seasons, you never felt alone.

When we came to this territory three years ago, we went in search of an oak that could be another anchor tree. It could be this one in the woods I climb in, I said to Mark, or this one by the gate that overlooks the deer rutting ground, or the one in the lane, the oak I can see from my window, its branches burnished by the sun as it sets. We sat at their roots at sunrise. They were old and gnarly and welcoming, as Suffolk oaks usually are. But it soon became clear that none of them would replace our old tree companion.

That’s when I realised it was no longer about me and my individual special tree, providing solace and inspiration in difficult times: our new territory was the set and setting for an ensemble practice. Wilder and older than our former homeland, with an assemblage of oaks that were connected underground by an invisible mycelial network that ran across the land, in fields, down lanes, in copses that skirted the coast.

That first winter solstice morning, after the initiating fire of our workshop series, we sat at the roots of one of the oaks in the woods, and waited. It was misty and cold and we couldn’t see the sun. Suddenly, a wren appeared and sang loudly above our heads. Then she flew off and a robin took her place in the branches. We looked up in astonishment. When I went to see where she had come from, I found a holm oak.

There is an ancient woodland myth about the solstices: a moment when the English oak (deciduous) and holm oak or holly (evergreen) do battle over the rise and fall of the year. Their exchange is mirrored in the song and dance of the much loved emblematic birds of England – cock robin and Jenny wren. Even now in our neighbouring village of Middleton the Molly dancers and musicians, dressed in black coats and wreathed in ivy, lead the people in a sombre procession to honour the demise of the ‘King’ wren on Boxing Day, and afterwards dance outside in the square.

And the reason I am telling you this is that during that liminal time, when the grief of losing a home we loved had yet to settle, an extraordinary thing happened. We realised this ‘new’ place was speaking with us. An augury that could be termed an extra-cognitive event but actually felt like a miracle. Because in ordinary linear time, you think the myths are myths, a human invention, and no matter how genuine your small endeavours might be to remind folk of the Earth’s sentience, you don’t always know it for sure. And then mysteriously, in ancestor time, when you least expect it, the myths come alive in front of your eyes.

Robin, wren, bee eater, kingfisher.

Oak.

Shelf

I came across Tyson Yunkaporta’s startling manual last year, and when I read it the work we were doing with the stone clock in these years suddenly fell into place. I realised that holding the fires was a way of engaging in what he describes as an ‘increase ceremony’: a thickening of the web of correspondences between place and people, ancestors, and the more-than-human world. A sharing of ceremonial culture, even though we were continents apart. As the consequences of modernity squeeze us in a death grip, connecting with the ancestral world, breaking out of our box of clock time, increasingly feels like the most radical act any of us can do.

Told in a series of ‘yarns’, as he works on different ceremonial wood carvings, Yunkaporta describes five ways of seeing from an Aboriginal perspective – kinship mind, storytelling mind, dreaming mind, ancestor mind and pattern mind. All five help perceive the land and ourselves within it, kin with creatures, rivers, rocks and sky. This knowledge is embedded in ritual, storytelling and practice that hold communities and cultures together, so human beings can be ‘custodial’ for places and living beings. We have a thousand-year clean up ahead of us, he reminds us, and generously, humorously, fiercely, hands us the imaginative tools to begin the work.

EIGHT FIRES PRACTICE If you would like to read further about the stone clock and how to maintain a fire practice in the coming year, all the tools, examples and stories can be found in our full colour Dark Mountain: Issue 24 – Eight Fires.

Coming up!

This is the last post before the Halcyon Days which start on Thursday. Paid subscribers will be receiving a Winter Solstice Letter, with an opportunity to meet up and share practices in the new year. If you would like to join us, do sign up for a paid subscription. All subscriptions are much appreciated and go towards funding further exploration and writing.

Many thanks to all of you for supporting this solo and ensemble work, for your engagement and attention. It’s wonderful to know it is out there in your territories! The Red Tent will be pitching back at the end of the month with further voyages in metaphysics, writing practice and culture-making. For now have inspiring Halcyon Days, convivial feasting and a roaring solstice fire. Love and mistletoe, Charlotte

Thanks Wendy-Ann. None planned at the moment but If there is further take up for these sessions, I will let you and other paid subscribers know. All best wishes Charlotte

Dear Charlotte, I reading this. Back in 2016 you brought your pocket of stones to the foot of Newtmber Hill at Saddlescombe Farm in the South Downs just outside Brighton. You sent us off to sit with the land and return with our tales. I had sat propped up by an oak overlooking the Devil's Dyke, and the land told me a different story. In the seven years since Newtimber Hill has become my liminal place where I regular sit, create ceremony, remember my ancestors, the ancestors of the land and those buried in the barrows on the hill. They've told me their names, and I return through the year, each year. In 2020 I undertook at all night Utiseta on the Bronze Age barrow. It was powerful.

This solstice I will be sat around a fire with a group of women in the heart of the Sussex countryside.

Solstice blessings to you and the stones.

I carry flint in my pocket.

Serena