The dead in the menhir stand in front of the living to keep them company.

– John Berger, The Vertical Line, 1999

There’s a tumulus near where I live by a crossroads known as Five Ways. It is crowned with birch and rowan trees, and it was here one winter solstice I found the deer skull that now rests on my mesa. Another mound further north, circled by black poplar and oak, is where we often go at spring equinox to lie among the wild daffodils, and the bluebells in May. These are not the great barrows of the grassy downs of Wiltshire, or Dorset. You would not even know they were there, unless you had studied a map. But when you sit in these places you can still feel the presence of those who are buried there, not your kith but your kin. People who once lived close to the land and these ancestor trees, to the deer who thread through the bracken. People who once waited in these stony places for the light of the new sun to fall into the chamber, holding the breath of the year.

We are not yet at solstice but have just passed Samhain or All Souls, when the dead are close, and the ancestors whose names we do not know, who keep the knowledge of how to be human in alignment with the Earth. Mexican and Georgian families feast with and honour the dead at this time of year, knowing they inform the living at all strategic points in their lives; but how can you find this sustaining depth of time in a deracinated culture, obsessed by history and haunting?

A time practice differs from a space practice, as it exercises the imagination at a deeper level. You are not looking outwards in all directions, as you do when encountering the territory, you are looking downward into the invisible dark. You begin with what you have at hand, your own memory locker. not because you wish to construct a self-important family tree, but because there are clues about the effect of the work you do at a metaphysical level.

So this is the practice: first to find those heirloom clues and then connect with the human and non human ancestors we don’t necessarily know, who might have our back in this difficult present. We are in search of a lineage for the unseen work we do in these hard times, a measure that can tells us how we need to align ourselves. A tumulus is a good place to start or any burial ground, under a graveyard yew tree or holm, letting you follow their roots into the bony Earth.

The past is a treacherous place, especially for a writer: you can get waylaid by all manner of skeleton cupboards and dark houses that properly belong to the reparative and necessary graft of nigredo. But we are on the rubedo path here, so we pass by the mother- and fatherlands, and walk towards a farther generation.

This journey begins in Harrods food hall where I am lost at Christmas time aged three. Oh, you might say, a memoir! Are we not where we shouldn’t go, with that moment your father has let go of your hand? Wait, I say, because there is a link in time here: my grandmother also went missing in this department store aged three at the end of the nineteenth century and was found by her horrified parents jumping up and down with her brother on a brand new mattress in a shop window. A crowd had gathered outside the store, entranced by the sight of two English children, bouncing and shrieking in delight in Chinese.

The children had learned the language from their ayah in Bangkok, where their engineer father had designed the bridges that crossed its many canals. Here’s the clue. Because my maternal great-grandfather was also a builder of bridges in the industrial north of England.

I am not an engineer, nor have any kind of mechanical or craft skill. Unlike my grandmother, I am a terrible needlewoman. But I have put my hands on these typewriter keys all my life, entranced by the myriad connections that the act of writing can reveal. It is an entirely structural attention. For metaphysics you need to not be distracted by the story, even a good one, but instead look at what lies beneath everything: the river beneath the river, and the bridges that cross that river. What you hold dear in your hands.

Looking back now, I can see how while my typewriting hands have been forging texts, my metaphysical hands have been helping restore the bridges that once allowed everyone to cross dimensions and access the intelligence of this ancestral Earth. This re-forging of links in the imagination contains a paradox: it is a solo work but you can’t do it on your own. It’s an ensemble task.

Desk

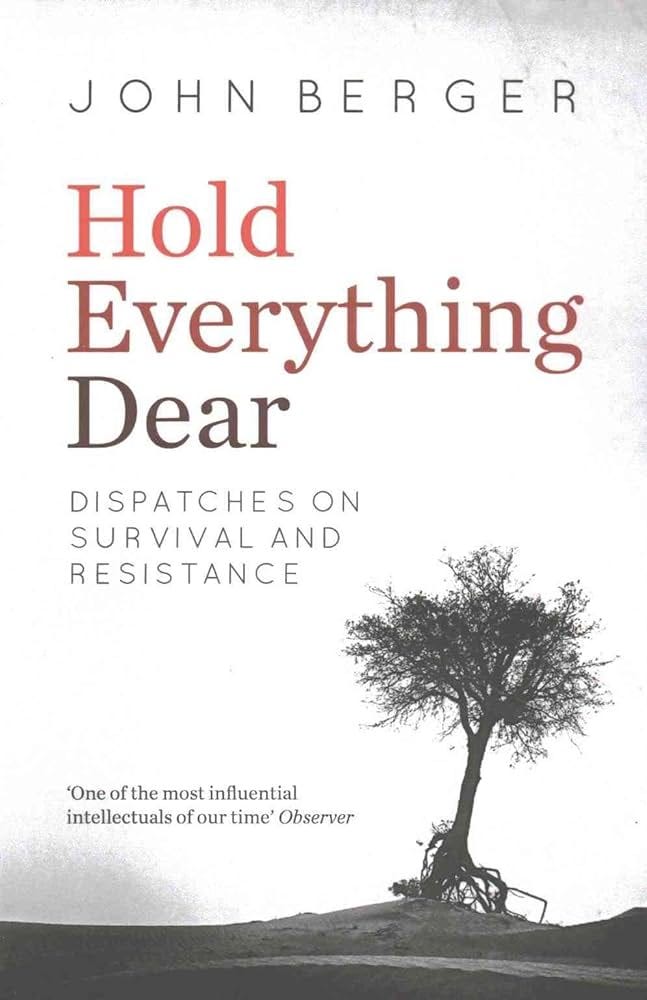

There’s a table in a book called Hold Everything Dear, and on it there are two cups of Turkish coffee. This table is in France where John Berger is writing a small devastating collection of essays about resistance and endurance that he will publish at the age of 82. He is speaking to the dead: an artist he once knew and the poet Nazim Hikmet who was hounded for his political beliefs by the Turkish government and died in exile in Moscow. For a long time now I’ve thought that having a lineage of writers and dissenters meant being close to them, as comrades, in the way Berger is in his address to the poet whose dying wish was that his bones could be buried under a plane tree in Anatolia. The future is fraternal, he tells us.

But when I contemplate this idea nothing comes; the claim feels presumptuous. Lineage after all goes two ways. So I go to the place where I often practice speaking out loud before a performance or teaching: a passage of birch trees that leads to a quarry, wading through the now flooded river to get there. Suddenly, as I am walking past these silver-limbed trees, I find myself in another place, far from any desk or political event. I am underground in deep time: Berger is speaking about the granite menhirs of Corsica and the limestone cave at Lascaux, with its ochre handprints and painted wild animals who live in the great Now of time. It’s from a performance that took place in London in 1999 called The Vertical Line. Part theatre, part archaeology, the writer and his fellow performers had taken small groups of people down a spiral staircase into the darkness of the disused Strand Tube station to experience a 30,000-year-old journey through time.

If you are an artisan, you might feel the hands of a master mason or baker in yours as you learn your craft; a fiddle player might hear an assemblage of musicians who have played the same reel through the centuries; a Zen Buddhist may sit in meditation with the ancestors of their tradition sitting in a continuous line behind and before them. No one instructs writers how to write. We read vast libraries of of books when we are young, and learn on the job. Creating something out of thin air is our art. Sometimes however you encounter a work that takes you in a direction you did not expect. You learn to treasure these moments.

This is one of them. I never went down those 122 steps at the turn of the millennium but I came across a recording of the event by chance in an exhibition celebrating Berger’s life. I realise now it is not the writing of books that links us but the transmission of a practice, the revealing of how to see in the dark, how to guide others down the vertical line, across the divide of time.

The clue lies in the stone.

Studio

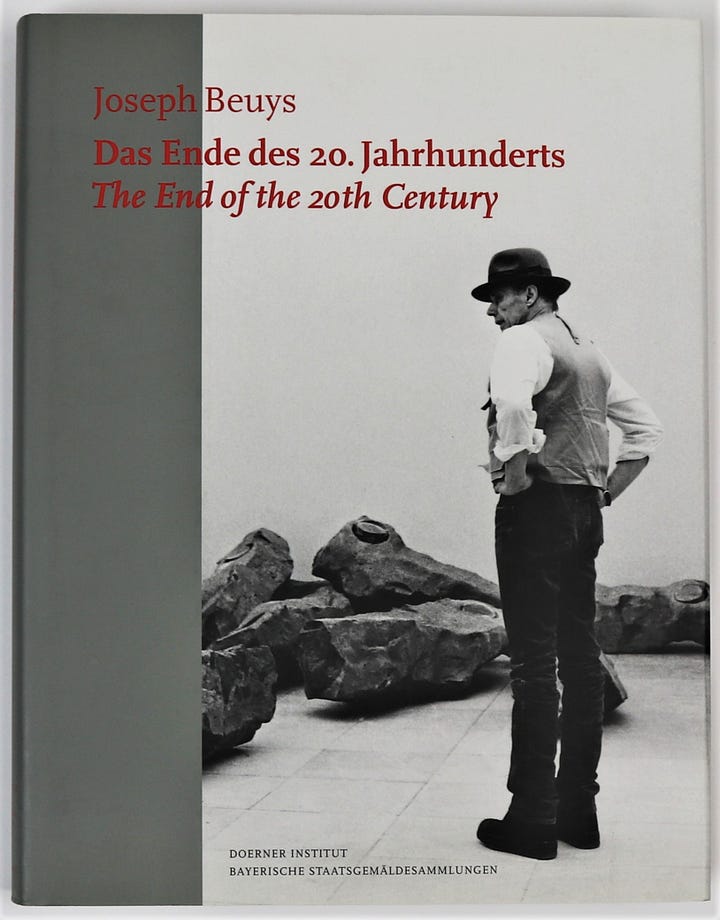

A some point the stone enters. You meet the mountain, you sit on a boulder, you hold a stone in your hand: time opens in these unexpected moments. Somethings starts, and also ends. At the end of the 1980’s, I stumble upon the artist Joseph Beuys’ monumental work ‘The End of the 20th Century’ in a Bond Street gallery. The stones are hewn from basalt, the volcanic rock of the seabed, a stone that will also form Beuys’ perhaps most famous late work, the planting of 7,000 oaks in the city of Kassel in Germany. On a video, Beuys is telling the world: in the future everyman will be king.

The dark blocks and his voice have transfixed and shaken me, as if waking me from a dream. You could say this encounter marked the moment I walked out of art galleries and stopped writing copy about the shiny and superficial things you could buy in the metropolis. Because not long after, I went travelling in search of deeper material. I went looking among the mountains of the Sierra Madre and the Andes, the sky islands of the Chihuahua desert, for a clue of how we might, as people caught in the wheels of history, start again from the beginning.

But it wasn’t until I returned to these flatlands and began to work with these tumulus trees, sitting at the roots of birches and oaks and rowans, that I found a way of teaching groups of people how to encounter the land in time. How you could repair those canyon-spanning bridges by immersing yourself in certain places and letting them speak to you and you with them. Originally these small gatherings were set in wild places, walking out into a moor or forest or up a hill. But when the workshops went online during lockdown, people would make solo ventures into their home territories in the week, and then share a creative piece of work with everyone in a follow-up session.

‘I had left the task to the very last minute,’ she said. ‘I just could never find the time, but yesterday I had a terrible row at supper with the family. I was furious. It was nine o’clock and pouring with rain but I just had to go out.’ The woman stormed out into the howling night and drove up into the Downs above the town and stumbled towards a stone barrow that was way off the track. Somehow the storm inside of her became the storm outside of her, and she sat down by the stones, in the wild and the wet and the dark, and she laughed. I felt the ancient spirit of the place all around me, she said, and felt entirely liberated.

The encounter had broken open the door of time.

Henge

Beuys left no instructions to the work’s curators regarding the layout of the final version of his 44 basalt blocks, except that there should be a path between them for people to walk through. Unlike an ancient circle or henge, these stones are not standing, aligned with the stars and the solstices, but are lying down and disordered. They show the end of this quintessentially modern century as fractured, broken like the masonry of a bombed city. Yet in each block you can find a sculpted funnel, lined with felt, clay and the polished excavated stones – a space that holds the possibility for a future, embedded in the ur-material of the planet; small tools for a ceremony hidden deep within the salvage. In the future everyman will be a shaman.

When I imagine these stone-titans side by side, I see how both creators broke the mould of how the artist or writer acts within the collective; what their presence brings; how their work can open your eyes to new and ancient ways of seeing, show how we might hold the living world close, the earth, the creatures and trees, framing everything we do within a social, political, ancestral context. When I look at their furrowed faces, I realise that it is not the individual writer and artist who are the lineage, but the communal function of the work they leave behind. The future is fraternal.

This why you follow the grandmother footsteps first. You need a sense of your own metaphysical craft to find your lineage, and how it ties in with your ordinary working life. You think that it is held in a faded Victorian photograph, a single line of famous figures stretching back behind you, or a diagram with names on it in horizontal time. But a lineage resembles more a constellation, a constellation of people whose work holds a similar intent to your own: an imaginal bridge woven across time and space, to which you can add your own vital strand. This constellation you learn to find in the dark is always there, like the Great Bear or the Pleiades, so you can know where you are on this Earth, and that you are not alone. Your work is invisible. No-one gives you acclaim in the world of galleries and shopping streets. But the bridge builders know you. You feel the presence of them as you remember: as the archaeologists felt the Palaeolithic painters in the caves, as the woman felt the ancient spirit of the Downs, as you feel your kin among the birch trees on this tumulus. It’s a sense of being held dear in all time.

Our kin buried in these places knew their deep time ancestors were not human but the bridge-builders of life: the animals, the trees, the wind, the ocean, the mountains. A constellation of engineers who created everything. For them they feasted, made ceremony, marked time, sang, danced, kept vigil, kept their human world in alignment.

The stones they left behind are their record keepers.

Thanks for reading everyone and hope to see you again soon.

If you would like to read further about working with territory and plants, you can find more encounters in my book 52 Flowers That Shook My World (PDF). Paid subscribers are welcome to a free copy if they sign up. There will also be an opportunity to join a small discussion group about these practices in the new year. Do get in touch if you are interested.

Meanwhile next month I am co-hosting a series of four sessions on creating a land-based practice, around the Halcyon Days of winter solstice, based on Dark Mountain’s new handbook Eight Fires. All welcome. You can find more details and booking here.

What an amazing piece. Such wisdom and so many teachings here and you bring them together simply and powerfully. I'd not thought of those connections in time as constellations - that is really helpful. Thank you!

A lot to reflect on here. This ex-pagan and morris dancer finds much in resonance.