The ice is cracking, a squeaking satisfying sound, as you step on the frozen puddles on the way up to the sea cliff. When you get there you breathe deeply: in and out. The sun is roaring to the south, the land is frostbitten, held in the grip of winter, but before you the light streams through the reeds, bounces off the waters of the marsh pools and sea,and scalds the eye. Transfixed, you feel you could expand into limitless space. And then you notice the dome of the nuclear power station and its army of pylons that march away across the land. For a moment you hold both in your sights. The exorbitant power of the sun and its dark collaborator on earth. Is it possible to hold such contradiction? You find yourself wavering, wanting to choose one or the other.

In that falter, you notice a figure crouched on the beach. What is she doing? Suddenly you realise it is yourself beside the horny stubble of a seakale plant, nestled in a shingle bank. Your hands are sifting small wet stones. You’re looking for amber. You won’t find any of course, but that doesn’t matter. The search is keeping you by the plant, long enough to realise that this is where you will begin the story of the uneasy chair.

The story begins to the north at Lowestoft where Mark and I once undertook a slow walk down this coast to Aldeburgh, not knowing which way to proceed. We were in search of different coordinates to steer our lives by. The walk coincided with a sudden massive flood: when a fierce northeast wind, combined with unusually high tides, had surged and inundated the land. We called it the sea kale project, after this plant that holds fast in the shingle, its long tap roots anchoring it, even in the roughest storm.

The reason I wanted to tell you this story is not to relate what happened during the walk, but afterwards, the result of engaging with a territory. How when we set off I was a disenfranchised writer who had not been published for 12 years, and by the time we arrived at the Martello Tower in Aldeburgh I was a community activist. On the Sailor’s Path to Snape I met someone who commissioned a short piece about the walk. And at the end of the article, I invited others to watch the sunrise at Lughnasadh with us on the dunes. And after that there was no stopping me.

The walk had also coincided with the rise of blogging and social media where you no longer had to wait for agents or publishers to allow your words to be read. Suddenly everyone had their hands on the keys. It was a liberating moment. I must have written over 400 blogs and articles in those heady times. There are many reasons for writing of course. Writing to get noticed, liked or admired, to join the literary establishment, to pay the rent, to articulate (and sometimes offload) your suffering or experience. But it’s important, as Donna Haraway reminds us in Staying with the Trouble, to know what story is telling the story. I began to write again in 2008 because I realised I had a story about ‘powerdown’ and radical change that fellow climate and community activists undergoing similar shifts in their ordinary lives wanted to hear about.

Writing is not a neutral activity: it is making certain demands on the reader’s attention. Nor can it be assumed to be an act of rebellion, or moral stance. Most professional writers write as part of the entertainment wing of Empire, even those who criticise or satirise it. All words can be made to fuel the algorithm of Progress.

So, what you write depends on the frame in which you write and your intent for doing so. What you wish to give back to the world. The Red Tent is strictly metaphysical, so this series will be about writing to connect with your own intelligence, your own original voice, the parts of you that are repressed by civilisation, edited out by the superficial world, gaoled, dismissed. And then to transmit what you know to your fellows. Because, as I found out in many years of grassroots editing, everyone has an original story: but can it be told well, and does anyone want to read it? Because, in spite of all the notebooks and book drafts in those wilderness years, it was that small piece published in a local magazine that broke the ice of what felt like perennial winter. Because no writing, no story, really exists until it is listened to.

Metaphysical work is challenging. It demands you perceive the world from different viewpoints, when our capacity to see is locked in a silo of our own and civilisation’s making. But if you practice it you will have the fortitude to hold the reality of what is in front of your eyes without splitting off into ecstasy or powerlessness. To hold a different sense of time that goes from the fossilised cliffs of Pakefield to the industrial infrastructure of Sizewell. If you can stay with that troubling vision long enough to allow the birds to appear, for the sentient world to speak with you and you for it, you might catch a glimpse of a very different future.

So like the dancer who starts by learning the five positions of the feet before they learn the steps, our practice starts with three positions of perception. As we stand on the cliff edge and hunker down on the beach. And then, swinging in the blue sky above, from a bird’s eye perspective. We need all of them to write well.

CLIFFEDGE You see everything in front of you in all directions. Here, down the coast, across the marshes to the far horizon. It’s clear. You get the big picture. The broad sweep. We love writing from this position because it allows us to Know It All. But boy, those sweeping statements can be boring to listen to. There are no feelings up here, no physical senses, no suffering. You know that voice. It can be smart, ironic, but also pompous and domineering. It’s full of airy abstracts, ideals and ideologies. Most of Western education is taught from here, the attitude of the politician’s speech, the big hitter essays, all that talk about the human race and They should do this and that. It’s key to see the bigger picture, but not to fancy yourself in the robes of judge or professor. You need to put your human feet on the earth. Run quickly down the cliff to the beach. Mind you don’t trip on your cassock!

SHORE Here we are on the beach intently examining the purple nodules on the sea kale, imagining how they will become crinkly crimson leaves, then large green-grey ones, then umbels of fragrant flowers the size of dinner plates We’re taking in the detail, what it feels to be upfront and personal with a plant, with our inner feelings, our experiences. Here you have all the closeness and creaturehood that was lacking in the long cool stare from the cliff.

But ooh, we can be indulgent in this me-only position. Writing from our own tiny corner of the beach, nursing our special nature moments, our sorrows, our failed relationships, our dysfunctions. We need to look up and get up to that cliff lickety spit, and bring some space and light into our swampy attention. Let some other beings in!

THE BENCH But lo, what is this half way up the cliff? A respite? It’s a memorial bench for a couple who used to sit here but are now no longer alive. Ah, you say and sit down. What a relief! But this is a dangerous place to stop. Tired people and ghosts linger here. Unlike the feral driftwood seat at the Sluice, it is a civic resting place with half a view, a compromise, a status quo ‘safe’ space, maintained by the establishment. All kinds of sentiment and secure opinions are allowed here, And most of all, the luxury of seeing the nuclear power station as just a white dome in the distance, and the sun as just a lovely sunny day out.

Writer, this bench is a trap. You are not a holidaymaker. The proper position is on the cliff with a stiff breeze blowing, where the National Trust tells you to stay away from the edge; or down among the frosty stones, looking for treasure by the gnarly roots of the toughest brassica in Britain.

We are in the metaphysical business. So there is no sitting comfortably and listening with mother. This is the uneasy writing chair where you are both the person sitting in the chair having the experience, and also the one observing yourself. The dialogue between the two, the struggle with paradox, is what matters. It is hard work, you protest, all this up and down! Yes, I agree, but look! With all this switching of positions, you are getting nimble. And warm. The cold has vanished.

And now you are ready for take off.

BIRD’S EYE This heathland cliff overlooks Minsmere Bird Reserve. On a high summer morning you can stand here and be surrounded by a swirl of sand martins as they teach their young to fly from the citadel of nests below your feet. If we are anchored with the sea kale, steady in our gaze, we can soar above with them, to look at ourselves in both positions and see what our small perceptions are doing within the invisible fabric of things, in these crowded airwaves, in the imagination of the world. It’s an unnerving moment, that split second you let go into the wind and fledge. And also a liberation.

Cader Idris

What, you might reasonably ask, has any of this got to do with chairs? Aside from the fact you sit on one (a lot) to write? Bear with me, as we change direction and go west into the hills of mid-Wales, where back in time (2002) I am recovering from the shock of being uprooted from the southwestern American desert. I am climbing an unknown hill on the first clear day after weeks of rain. At the top, puffing and panting, I find a stone circle and sitting down on a boulder, gaze at the swathe of green valleys below. There’s a mountain peak in the distance I keep looking at. I don’t know this yet, but it’s Cader Idris, the seat of the giant, where it is said if you sit on his rocky chair for a night, you will either wake up mad, or a poet.

I was neither when I came down from the hill, nor when I climbed Cader Idris later that spring with Mark and Arthur and Will, and we were thwarted by mist. But something quelled in my heart. My exile from the desert I came to see was also a return to these ancestral islands, and though it would take many years to make myself at home, writing was what made sense of the disruption. It brought me back.

Every writer needs a territory that is part of them, that expresses their nature and informs their work. It is not always the place you might choose, or prefer to be, but where you find yourself in dialogue with, come what may. This is a metaphysical practice rooted in earth and sky so this territory could be anywhere: a landscape of rolling hills, a wilderness, a city neighbourhood. But in times of collapse all of these are likely to be damaged or compromised in some way by the agents of that collapse. You don’t want that to be the case but this is the world. What is.

Our challenge as writers in this practice is how you hold that knowledge in your mind, body and heart. How do you stay with the troubling facts of it all and not collapse yourself?

I walked the last stretch of the sea kale walk towards the Martello Tower again last week on the narrow spit of land between the Alde river and the North Sea. The sun glanced off the salt waves and the running tidal waters either side of me. It was exhilarating. But in front of me tall radio masts scored the horizon, the boatyard lay flooded at my feet. Here was the northeast wind ruffling the feathers of the black and white turnstones as they ran in and out of the puddles in the broken road. Bitter cold, relentless, you felt there was nowhere to hide from that wind.

The little red-legged birds kept splashing, shaking, dipping in and out, nonetheless.

The Shack

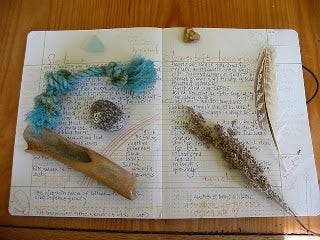

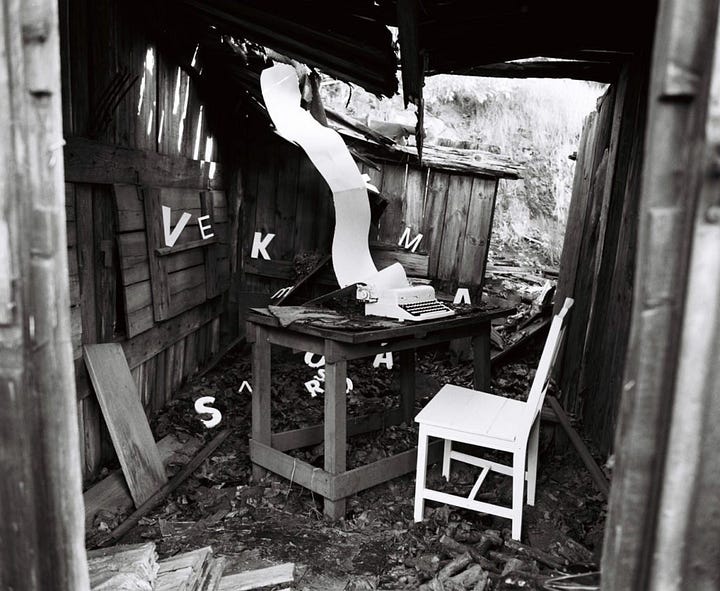

(Left) This is the setting. All is calm, you have a lovely writing desk. The sun is on the sea. The notebook is open. A whole day stretches before you like a cat (Right) This is what is going on inside. Ha, the torment! The indecision, the block, the indulgence. Everything is a mess! The place is a shambles. It’s always so. Creativity comes out of an unholy mix of structure and chaos. The great paradox of it all.

Why is Annie Dillard a guidepost for our writing practice? Because she is very clear about set and setting, and the business of grappling with sentences. Because she is a brilliant demonstrator of positions: a stellar perceiver from headland, shoreline and sky. The Writing Life ends with a praise song for a stunt pilot, as she witnesses him manoeuvre his craft, conjuring extraordinary patterns and shapes in the air. It is a metaphor, of course, for the act of writing. Daredevil, inventive, beautiful. Done with all you have because you can, because you are here, alive and original in the world.

This slim book of instruction starts however with an earthbound desk and chair. Before any aeronautics can take place, you have first to find your alchemical crucible, your red tent, your kitchen table in a monastic cell. Then you give yourself time to sit on the chair with an intent to hang on in there. Dillard writes in a pine shed in the woods, in a borrowed cabin on a remote island overlooking the sea, but crucially she turns away from the window.

Appealing places are to be avoided. One wants a room with no view, so that imagination can meet memory in the dark

The Uneasy Chair has appeared as a teaching in many places. Though a writer and editor of creative nonfiction, I have taught poets and novelists, academics and artists, eager activists and weary reporters. I’ve sat on uneasy logs and pavements in festival fields and protest camps, on school chairs in university lecture halls and abandoned classrooms, around a long table in a house that once belonged to Ted Hughes. I’ve taught classes on Zoom calls, on a boat in a wavy sea, in the middle of a winter forest with a giant hat adorned with dead owl wings and twigs on my head. Reader, I have been there, as I am sure you have too.

And though we might wish to claim the heroic label of ‘writer’, none of us would willingly sign up for the night watch: to sit in a gaol cell with Vaclav Havel, or in the Whitechapel spikes with George Orwell, at impoverished desks alongside Cesar Vallejo or Elizabeth Jennings, or any manner of deep and difficult places history and fate and conscience can place a writer.

With luck, we won’t find ourselves in a gulag or a war zone but this fortune doesn’t make the task of wrestling with the part of us that is indentured to the establishment of family, church or state any simpler. It doesn’t make the work of holding all the sunlight of a winter’s day and the terrifying reality of a nuclear power station by the eroding sea any easier.

Because this is the inner territory of the uneasy chair once you decide to sit on it. The constructed world is as it is because we are bullied into splitting off into fantasy realms, or into ruts of despair, or nihilism. We are trained to avert our gaze, to not pay attention to what is in front of our eyes. The Red Tent practice is about retraining perception to see directly, where writing can be an ally, a testament of what happens when we attend to the small corners of our territories, a portal from our mesa in hand.

When we struggle to climb the cliff, to fly in our imagination, to put words on a page, to start again, to remember, something shifts. You can’t measure or pay for that shift. You just have to let it happen through you. Enter the metaphysical shack each day and answer the question posed by Annie Dillard:

How do you prepare yourself to enter an extraordinary state on an ordinary morning?

Later in this occasional series we will look at different aspects of an existential writing practice: rigour, vigour, self-amusement, tone, voice, relationship with the reader, with the more-than-human world, how to work with real-life material and find your 'medicine story', the quicksilver thread that can pull us through.

There will be a main introduction for all readers but if you would like to follow some of the close work and exercises – the tools and the tech – do sign up for a paid subscription.

Thanks everyone for reading and to all my The Red Tent supporters. Your backing is much appreciated. Hope to see you all again soon!

COMING UP!

Meanwhile, this March, if you would like to find ways to engage in a collaborative, land-based practice during the year, I am co-hosting four online Spring Sessions, inspired by Dark Mountain’s new handbook Eight Fires. Following on from the rich underground territory of the Winter Sessions, our spring explorations will be set around the days either side of the spring equinox.

We will be working with the water bodies of local territories (ponds, lakes, springs, streams, rivers, seas), with emerging plants and wild wilds, gathering material by the shore, encountering myths and making ceremony. to celebrate the seasonal shift as the year crosses the bridge from the dark months of winter into the lighter months of spring.

I’ll be co-hosting these sessions with fellow fire- and waterkeepers, Mark Watson, Caroline Ross and Lucy Neal and it would be great if you would like to join us on the bridge. Further details can be found here.

That's a great question posed..how to enter the extraordinary in the ordinary. I think for me it's tuning into to see the extraordinary within the ordinary. Things we take for granted easily become ordinary and seemingly mundane, lacking inspiration. Take a simple pencil. It is a pencil, ordinary, I have so many pencils about the house.

But when I start to consider the extraordinary within that simple pencil, my imagination is sharpened...the pencil become the Caran D'Ache watercolour pencil with my name stuck on it by my mother, one of a tine of individual named pencils that she bought for me as a child, named so that I wouldn't lose them at school!

The pencil has become the small stub that once graces my grandmother's handbag, along with her smelling salts. The branded pencil that I picked up a hotel room many moons ago that transports me back to another life.

The humble pencil is no longer ordinary.

Thank you Charlotte. You have breathed some deep and grounded clarity into my writing life, and the web of my relationships, allowed me to feel the depth of the intention that guides my writing these days, something in my bones, my blood, my fascia, that has a fire of its own. And allies, friend, beloveds. I stand as the guardian of this fire, protecting it, especially when it falters, flickers, assaulted by the great storms of our collapsing world.