Scribe

A final adventure in The Uneasy Chair

Hello dear readers and fellow writers. I’ve waited a while for this piece to emerge. I was originally waiting for the event that would underpin it: an outrage rally on my neighbourhood beach, protesting the devastation wreaked by the construction of two new nuclear power plants. But then, as I sat down to write it, I found a deeper disturbance inside my heart, towards which this piece advances.

When you tell people you are a writer, they usually ask one of two questions: do you need to be disciplined, or how do I get published? Often, they are looking for a opt-out clause (oh, I couldn’t do that), or for fame. And the simple answers I give are: no, I write to deadline, which means I leave things to the last minute and have no idea what I am going to say until my hands touch the keys. And no, I have no idea how you get published. The books that have made it into the world have always come about from chance encounters and luck.

However, there are more interesting questions that could be asked, one of them is: why are you a writer? This is my answer.

Francisco Ozuna stands on the mountain, as we stand in a protest circle in the searing heat, to pray for the Dragoon Hills The peak was about to be blasted by a German mining company to provide the European art market with marble dust. The Dragoons are sacred to the Apache and were once the stronghold for Cochise and his warrior band during the last Native American resistance against the white invaders. Francisco, brought up in Mexico, was coming back to the land his people had been hounded from 150 years ago:

’The mountain doesn’t belong to the Apache,’ he said. ‘We belong to the mountain’.

‘Why are you doing this? asks a timid woman, as Apache Ray, also returned to the Hills from LA, waves an eagle feather and sage smoke over her head.

‘Because we have to’, he replies.

Opening the door

Balsall Heath, Birmingham, 1978

John Berger once wrote this final defiant line in a searing set of essays about resistance, Hold Everything Dear.: ‘And yes, I am still, amongst other things, a Marxist.’ And so perhaps I will start there to say: ‘I am still, among other things, a writer’.

Something propels me to put my hands on the keyboard. And that drive is what makes a scribe. You have to. You feel duty-bound. You’re not literary, agents and publishers have told you will never make the grade, you are rarely commissioned, and have to curate other people’s words to pay the rent. Yet, here I am, writing to you.

And so, I will start at the beginning: not when I shook a toy rabbit like a rattle and spoke stories out loud about the animals, or when aged ten I failed to win the essay cup with a spellbinding (but badly spelled) tale about a storm, but in a squalid house in Birmingham in a street where every front room is taken over by a giant sewing machine, and middle-aged women sell their bodies for a fiver on the corner.

My friend Mel is yelling at me for destroying the Hull fishing fleet. Of course, I don’t possess such powers but I am Middle Class and therefore not on the right side of history, or his mood. Most people of my class go to Oxford, and proceed to a literary career without a hitch, if they are not torn apart by a system that shapes their every sentence. But here I am in Balsall Heath, aged 21, living with Andy and Helen and Mel, a former miner from Sheffield, who ran away to sea when he was 17 and only became immersed in English Literature because he went to a Trades Union college.

In this unfashionable Midlands university, I have found in the tools of Marxist critique, a way to face the fury of my friend. I am finding that having to question everything about your upbringing yields Material, so long as you are able to hold the paradox of both undergoing the experience and making sense of it from a larger perspective. The existential position that underpins The Uneasy Chair.

I didn’t know it then, but I already had the capacity, as all writers do, to hold to the moment, to what is going down in the room and stay fully conscious, when everything around you is telling you to fight or flee. You write because you find yourself facing the consequences of your arising, your culture, your time on Earth, and you know, in the core of your being, you have to make a move.

A slum in the red light district of Birmingham is not the Oxford library where my contemporaries are reading texts directed by ghost of F.R. Leavis. I am scrutinising texts though the lens of 1970’s politics and linguistics, encountering people from cities they will never go to, to discover the guiding theme of my working life: powerdown. I am finding and that my real ability (like that of most writers) lies not so much in the craft of writing, but in perception.

In those uneasy spaces, you are seeing a door. It is unknown but it is alluring. It shimmers with a light. It is scary, but you walk towards it anyway. You can’t help yourself. You sense the one thing, people never ask about writing: the capacity to move in a stuck place. How you can in this trapped moment become a strange attractor within the chaos of the world, and usher the future in.

If you want to know how to be a writer: walk to that door and open it.

Leaving the train

Westbourne Park, London, 1989

At Westbourne Park station I alight the train. Here I am in high boots and claret-coloured Jean-Paul Gaultier en route to the fashion dept of the Independent newspaper. David Jones, in rumpled white shirt and grey jacket, is on his way to the obituary dept of the Daily Telegraph. We greet each other as we step through the door, friends and fellow journalists. I can’t remember now if this is the morning the Tiananmen Square massacre shocked the world’s front pages, or that week, or whether we speak of it, as the train rattles eastwards across the city, But what I do know is that out of the corner of my eye, I see the last words of a poem: ‘they shape words, even in silence’. The words are Osip Mandlestram’s in a poem about Stalinist Russia, ‘You took away all the oceans and all the room’.

Where did it get you? he asks. Nowhere.

You left me my lips, and they shape words, even in silence.

David Jones was a poet from Wales, and all these years later, what I do remember is the gentle lilt of his voice and how unironed his shirt was. And how in that split second, when the poem appeared, I saw how we too were ensnared, caught in the maw of a system that had no use for us as writers outside those newspaper pages.

Once you see that, you are compelled by your trade to make a move. Months later I will leave my profession, and then the city. I will go to the mountains of the Americas in search of the future. Mark will be by my side, companeros for the next 35 years. That defection has been at the core of all my writing since.

I was not in the trenches of Flanders with the poets, or with Osip Mandlestram in the labour camp at Vladivostok, or with the young man who stood in front of the tanks in Bejiing that day. But sometimes their lines, their presences, appear to remind you of your real allegiance as a shaper of words.

I cannot claim any kind of noble cause as a writer. God knows I was never on the right side of history. But I was in the room, when you yelled at me with all the passion of a generation deceived. I was at the police station, and in the deportee jail, in the ambulance when you lay dying. I was on the mountain, I was at the nuclear power station. I did not shut my eyes. I did not turn away. And in the small print in the life of a writer that counts in places we may never know.

Powerdown

Sizewell beach, Suffolk, 2025

The thing about studying literature, Simon Barnes is saying, is that it stays with you whether you like it or not. He is comparing the actions of the Anglo-Saxon hero Beowulf to Pete Wilkinson, co-founder of Greenpeace, whose life we are celebrating on Sizewell beach. A man ‘who sailed out on a fleet of lilos’ to confront the massive ships dumping nuclear waste into the ocean. He was using the epic poem all Eng Lit students begin their word-hoards with to frame the human struggle against the titanic forces of destruction.

Afterwards I went up to speak with the journalist and lover of birds. The only word I can remember from my Anglo Saxon language class, I tell him is 'Hwaet! which is used by storytellers to call attention. He smiles and tell me the word he remembers is gūþ-hafoc (which means ‘battle-hawk’). Beowulf releases the emblematic falcon into the sky before he faces his third and fateful dragon, a battle he knows he is destined to lose.

‘Let’s hope,’ I say to him, ‘we do not have to let go of the marsh harrier after this.’

After the speeches and the music, the assembly walk in the warm summer rain down the shore past Sizewell A and B towards the site of C (and D), which has already swallowed whole fields and woodlands and fens in its mechanical jaw. We tied ribbons on the Harris fencing with messages of thanks for Pete and of defiance for the corporate behemoth that is turning what was once a heritage coast, a flocking place for thousands of resident and visitor birds and people, into an energy coast, to power a culture that can play with A1, buy bitcoins, fuel cars, and maintain the illusion you can live untethered to the living breathing planet without consequence.

Lesley has brought a picnic and so we sit down on my rug and eat it in spite of the rainclouds. I see a young man in apple green trunks swimming, and in the way you do on a beach, I follow him into the quicksilvery waves. Marion appears and asks if she can borrow my swimming costume. I realise then the man in the water is her son Joe, and how all four of us have known all each other now for 20 years, our lives criss-crossing in these community and activist ways. How we are all sitting together here in front of the nuclear power station (and an estimated 5000 tonnes of spent fuel lying below), holding a line before the sea.

When I look back at these moments, in the way Mark and I once held dreamings after flower visits, and follow the feedback loop I see the pattern in time. How this moment is every moment, past and future. The people before the machine, having a picnic, the child laughing on his father’s shoulders, the kittiwakes whirling about the cooling tower. The seakales stretching in all directions. Lesley, Pip and I watching the sea shifting in the dark light. How the blue scarf I am wearing is the blue scarf Mark was wearing at The Wave, when we first met Joe on the bus going down to the (then) largest climate march to happen in London. How you can take these moments and dive like a falcon into their complexity and reconfigure time.

Even though the warrior will lose the battle, he goes out anyway. Because that’s what he has to do. We went that day to say we were there. We didn’t agree. Our allegiance is not with the destroyer. We were not alone, we belong to this salty edge of the kingdom, with the birds, with the trees, with the sea, each other, in time. So the feeling amongst us was not one of despair, but of happiness.

The future is fraternal, wrote John Berger. Hwaet!

In the moment

The truth is you can choose any number of moments where your life pivots, where you took another path, where the door opened, where you were aware of its ripples in many dimensions, either then, or later when you revisited the scene. There were other times when my destiny was revealed, or I became acutely aware of being stuck in a small place and needed to move. But these are the three that presented themselves for this piece: they are all about liberation and they form a pattern, so I can triangulate myself in time and space, and give you an answer to the question: why am I a writer?

What these three have in common is power: power of class, of media, power that keeps the machines of civilisation going. If your task is to communicate what powerdown entails, every opportunity to do so will be presented. Not just to write about, but to undergo. It’s your materia. What making an alchemical move requires.

Sometimes I think about my old friend Francisco Ozuna, born under a cottonwood tree, last in the line of curanderos. How one night climbing the stairs with Mimi to our flat in the Miner’s Hotel. we heard him shout: Estas vergas, que? He was shouting at the altar of Indian saints and gurus and gods in the hallway. It is almost impossible to translate from the Mexican but a combo of these wankers and what the fuck gives you an idea. Mark (fluent in all thing Mexican) laughed his head off. They both roared all night, as at every opportunity one of them would repeat the phrase. Sometimes you need the voice of the place to come through you. And it doesn’t always take make the enlightened, politically correct sound you think it’s going to.

I told Francisco he would make a killing as a runway model in Paris with his wonderful profile, and he beamed. You think liberation, the work of powerdown, is the task of revolutionaries, but sometimes it’s a medicine person laughing at alien gods. And someone, who used to be a fashion editor in another country, remembering you.

In the red tent

On midsummer’s eve, on my birthday, I put up the red tent again at the end of the garden beside the raspberry canes. There are poppies and evening primrose and wild carrot down there and grasses as high as myself. The buddleias are dancing with butterflies. Two years ago, I sat at the tent doorway and watched the buzzards wheel above me and began this column. As the year turns from the zenith towards the fall, I turn inwards to ask the crucial question all writers ask as they face the blank page: What do I need to tell you? Is there anything else in these practices, I promised to share all those months ago, when Mark was still here, before the roadwork began, before all these shadows gathered in my heart?

Today a southerly breeze heaves the goat willow leaves, above me, and a kite sails past, a new raptor in the sky. I am always writing the same poem, Pablo Neruda, once wrote. And I am always writing the same piece. Because it is based on the same metaphysical obligation writers have: to love the Earth and liberate the human spirit.

We all have monsters we were sent here to confront, and I have, in my own way, confronted many of them: personal, social, political, metaphysical. But some of them are too strong to overcome, and one day you wake up and you know it. Even, though I have been a writer all my life, I find myself unable to muster enough words to justify the description. I sit down with this Uneasy Chair post, and realise that everything I want to say about writing, about metaphysics, I have already written more elegantly and passionately before. The truth is my final monster is unescapable.

‘Sorrow is exhausting,’ my friend Lucy said, when I told her I was so tired I could hardly stand up. That was a year ago. And the reality is, I am still exhausted by the loss of Mark. I have done my best to keep going, to maintain the house, the garden, the work (both his and mine), the practices, the flower visits, our friendships. Writing here at the Red Tent has give me some ballast, making sense of the partnership in which we were both scribes: Mark, a copious note taker of our practices; me, a creator of ways to transmit them, from books to collaborative blogs, from workshops to performances. Our partnership was based on his great capacity for presence, mine for making connections and communication. What spurred me to keep going with this column after he died was that fact I was continuing to honour those practices – and him. But I can’t pretend it is easy without the person who always loved the stories I wrote (as well as rigorously subbed and proofread them). To be able to show them to Mark gave them their shine and all their meaning. It really was a double act.

You need a reason to write. A desire to communicate what you see. A love for those sentences that whirl out of the chaos inside you that you temper with your heart and your skill. I have really loved them. Thousands of column inches about a thousand subjects. But as I look into my once abundant word-hoard now, I find the casket empty.

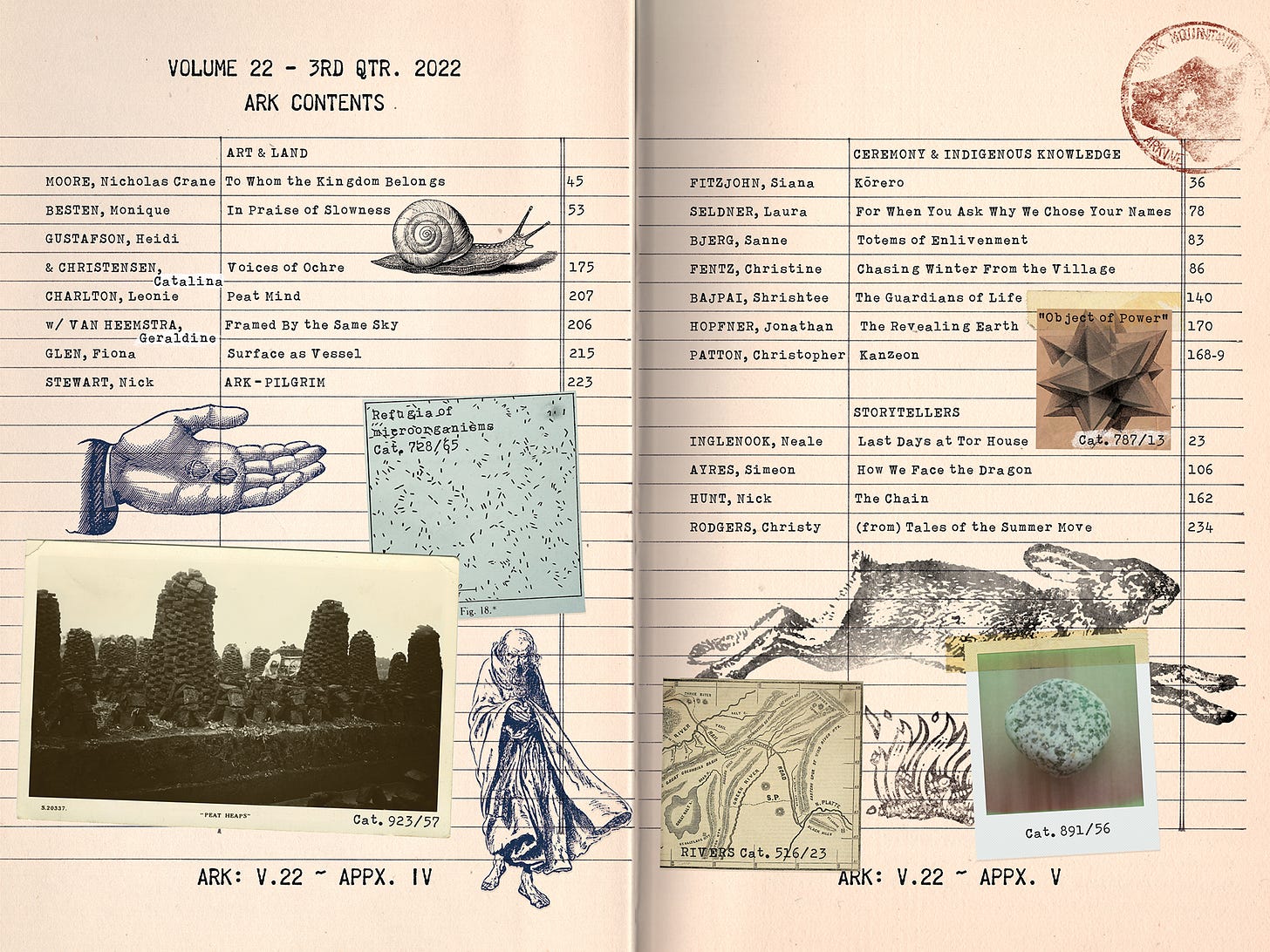

So, I think I need to take a break from this twice-monthly Substack. Maybe not for ever, and for sure I will be publishing some of my earlier work in the coming time, much of which has never been read, or published online. But I wanted to let you know where I stand, as a writer who values straightness with the reader above all things. I particularly wanted to let my 30 paid subscribers know, whose generosity and loyalty has offered some real financial ballast in a hard time, especially when we have had to tighten our belts at Dark Mountain. Thank you. It has been invaluable.

Thank you all so much for reading me in these months. It has been such a boost to see these pieces, both new and old, read by hundreds of people, and to receive your kind messages. I hope to see you again soon. But for now, hasta luego. Fly well.

Love and flowers, Charlotte

You gift us the true magic of writing - which itself is un fathomable , precious , timeless … thank you for making the effort and for pressing send - allowing us on the dance floor that comes to life with words- 🙏

Charlotte, you were here when I found Substack and one of the first I read. I have found meaning and reflection from the writing that flowed from your life’s journey. Connecting with someone who respected the Earth and all her beings, I felt less alone. I am grateful for what you have shared.

The wise intuit when to powerdown and breathe deeply. I wish for you that space.

With gratitude, Lyn