Hello dear readers - This is the third post in the Red Tent strand of The Uneasy Chair, where I pass on some of the writing ‘tech’ I’ve used when teaching creative non-fiction. In the intro post we looked at inner positions a writer takes, on a winter clifftop. The second, Undertow, at the territory of alchemical writing, at a spring tide. This post will also look at position but in relationship with the reader. And also the practice of memory. It begins inland in a field of thistles and tares in high summer…

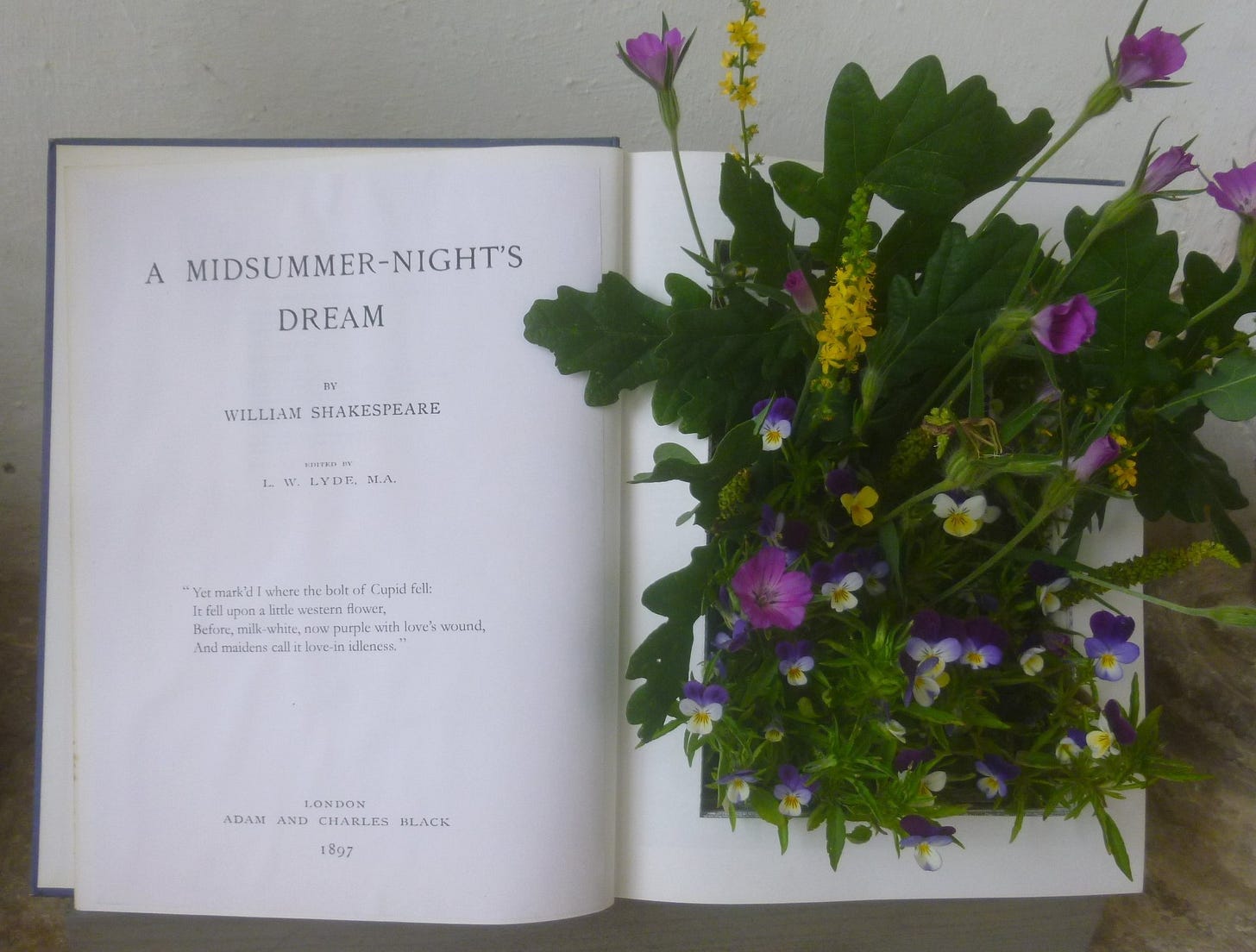

Last week I went to a field by a wood by a disused quarry that is now a community-owned nature reserve. It was the most magnificent sight I had seen in a long time, a vast flowering of agricultural ‘weeds’ that are normally suppressed by modern industrial practices. Huge stands of willowherbs, thistles, musk mallows, evening primroses stretched in all directions, with paths of scarlet pimpernel, speedwell, plantain and pineapple weed. Some corners had been planted for bees and other insects: the blues of borage and phacelia, interwoven with spikes of crimson clover. Larks sang overhead. It was as if some enlightened gardener had taken a full-scale regeneration of the lowly plants to heart.

So my question for this series is, how you write from that field, that extravagant post-monocultural diversity? Nothing original, new or future-looking, literally or metaphorically, can come out of a soil saturated with chemicals made from fossil fuels. But if you disturb the ground, get deep, you might just unearth the seeds of some extraordinary flowers. A diversity in yourself you never knew was there.

The field belongs to Rachel, who has made this woodland corner of Suffolk into a gathering place: with a forest school, field kitchen, woodland stage, and story hearth around which artists, skill-sharers and local elders meet. She also spearheaded a campaign to buy those gravel pits from a Mexican corporation, so it could remain in the hands of the local community.

We had met the night before for supper in my garden, with Keith and Gemma, underneath the giant fennel and Mark’s emerging sunflowers. It was a warm evening, so you could sit outside, and hear the thrushes thrash out their evening arias from the greengage trees, like a poetry slam. I have known Rachel and Gemma for many years, though our paths do not often cross. ‘How did you meet?’ Keith asked.

So we told our origin stories.

Rachel and Gemma could not remember exactly, but to my surprise, I could recall when and where we first met, what happened as a consequence, and even, in the case of Gemma, what she was wearing (‘Oh, that blue coat!’ she exclaimed, and sighed at its loss).

And I am telling this story because there is something about the attention of writers, about the practice of Earth-based metaphysics, that feels it matters for the future, and it’s to do with memory, and meeting people in a certain spirit. I met Gemma at Speakers Corner on a climate march called The Wave when she was 19 and starting up a housing coop in Ipswich. And I met Rachel in Halesworth Library when we had a conversation about Noam Chomsky when she told me I had to go to Varanasi (which I later did). Writers notice, pay attention, remember, and sometimes put that act of recollection into words in a physical form. It’s not just about the initial conditions of a grassroots friendship, but the collective frame in which you met. In a non-linear understanding of time, those beginnings determine certain patterns in the world. Everything loops back to them.

A key talent a writer can nurture is this full-bodied recall of a place in time: it is a primary function of the imagination. It means you can bring to mind an image of what happened, even 20 years ago, and see how that kairos encounter has shaped your relationships henceforth. It acts like a portal to a knowing of a person and the universe they carry inside them, a seed for the future. Your joint attention when you meet again is what nurtures that future. That feedback loop makes regeneration possible: a field of colour on a July day.

At the supper we laughed about how memories now are kept in the cloud or mobile phones. But storing memories in a machine is a slippery slope for people in a culture of amnesiacs. Real memory does not live in the mind, trapped in a linear storyline, as a thought. It’s in the body, in your heart; it’s the set and setting, a physical place and time. It’s a non-linear creature that co-exists with others. The imagination doesn’t think, it sees in images. So to bring the imagination into form, your words need to be anchored in the real world, not the abstract or virtual realms.

A good practice is to find your feet in a place and holding that perception, that memory of place, speak from there. Right now, I am writing this seeing my garden on that warm summer evening, but very soon I am going to go back in time and write from the features department of Vogue magazine at the end of the 70s where I learned my craft on a huge pterodactyl typewriter, while rails of frocks flew up and down the corridor.

The reader is your friend

Everything I learned about writing came from the days I spent in the features rooms of magazines and newspapers in the 80s, where I worked as a writer as well as an editor. As a journalist there are two desk gods you have to serve: one is The Deadline and the other is The Word Count. And in spite of advanced typing technologies, these exacting gods of necessity are still the ones to pay attention to now when you sit in the uneasy chair. Without these restraints, you can think you have all the time and space in the world, which is not only not true but also does not create the necessary hermetic container that allows any alchemical work to take place.

The Deadline is a reality check: it means that if you don’t write it on time, it won’t exist. You can put off writing that book/story/poem your whole life. No one will care, except you. The Word Count cuts the tendency to write over-long and indulgent prose, liking the sound of your own voice, or cleverness, too much, piling on the adjectives and other great sins. There is a reason that old-style subeditors used to cut from the bottom, as that is usually where the writer tends to go on. Oh, another thing, another connection I’ve just thought of….

In print, of course, you are restricted by the page; online the page never ends. It scrolls to eternity. In the absence of editors, questioning your motives, wielding the scissors, you have to become both writer and editor. Ruthless to the core, with an eye on the clock.

Since those magazine years, I’ve edited very stylish work (that is utterly superficial) and extraordinary stories (that are clumsily written). Either way, the toughest, most difficult thing to get right, and arguably what make most pieces end their editorial lives on the spike, is tone. Because as soon as you start reading the text, you find yourself thinking, Hmmm, this is just not right somehow. A piece might be saying all kinds of interesting things but how it being said ruffles you up the wrong way.

Most of this is caused by the position the author is writing from. Mostly when you read the piece, you don’t feel like a friend: you feel like the author’s ex-lover, or their mother, or that teacher who gave them bad grades when they were 10 years old. Or, worse still, a politician they don’t agree with and is personally responsible for not only ruining their life, but the class/gender/culture they identify with, and then the whole world.

There is nothing more difficult to read that the writer who feels lesser but writes as though they are in charge of the universe.

So when I teach writing I don’t focus on style, or even content, but some basics that are good to get down, before you even open the laptop or pick up a pen. And after paying due to the desk gods, come the human challenges of position and relationship.

The first lesson in both these is: the reader needs to be your friend. You see, unlike real life where walking away from someone who is boring or intimidating can be socially challenging, in the business of writing it really isn’t. People turn pages, they skip paragraphs, they press delete; they throw the book down, or banish it ignominiously to a charity shop. There are just so many ways to die as a writer. So, to command attention you need to bear the reader in mind, hold them close to your heart. If you want to say something intelligent or radical, or in our case, metaphysical, your work is cut out for you. Attention is hard won.

Successful writers can have you at the edge of your seat, but this, of course, is no test of quality; page-turning prose is not necessarily nourishment for the soul or mind (as any journalist can tell you). The reader, like all consumers, is fallible to junk text, and mostly wants what it wants: to be entertained or distracted, or feel superior, validated, vouchsafed in their own point of view. Writing can be an egoic business both ways.

But if you want to write something transformative, something alchemical that inspires a different outlook, to create new pathways in the imagination; if you want a reader to step into your shoes, stand next to you in a place they do not know, you have to consider them. They don’t owe you anything. You owe them everything. Without their attention, their eyes or ears, your text can’t dance. To exist, a story, famously, needs listeners.

People write for many reasons but core to all of them is communication. You have something to say and you feel compelled to tell it. If you are a storyteller you know that your capacity to do that depends on the concentration of the people listening to you. When you are writing, the audience is invisible. But that doesn’t mean they are not there. You want the reader to follow you down and over the page.

So, a good trick before you start is to ask yourself the question: am I the kind of person you would choose to share a railway carriage with? Because if you want the reader to travel with you, seeing the world through your eyes, listening, laughing crying, hearing whatever you are telling them, you need to take up a friendly position with them. You can address them like the old Greek islanders who, when they sing a song, lean forward and sing directly to you, as if inviting a dialogue; or, like George Orwell, as a congenial companion, he walks with you through the streets of Paris, speaking about Henry Miller. When you are talking, you want the reader to feel you are speaking with them and for them, endowing them with intelligence and know-how and experience, so that that paper-to-person relationship they won’t want to be anywhere else.

That’s a gift that some people have, a compelling voice, where readers are happy to follow them come what may, but that magnetism is not where it ends. If you find yourself admiring a writer for their voice, or their style (‘so-and-so is such a good writer’), well, that is no better than being impressed by the quality of a singer’s voice, and not listening to what they are singing.

It’s not about the singer, it’s not about you. The song is the thing.

The Box

Cambridge, 2022

For several years now, I taken some of those basics I learned on a deadline as a writer and editor and been teaching creative non-fiction as a way of understanding and responding to the world within the frame of collapse: to activists, academics, beekeepers, beginners. I’ve taught people to delve into their lives like a archaeologist, to search among the ruins and find the treasure, the shiny and beautiful things in the rubble of the past, and then share them. I’ve taught classes online and offgrid, in protest and festival tents, in libraries and retreat centres, in wild valleys and community gardens.

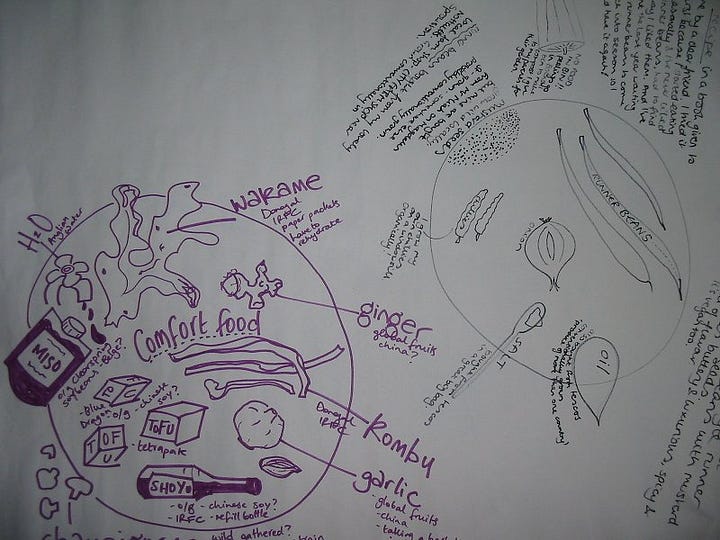

The last classes I have taught have been to post-graduates and lecturers, mostly social and climate scientists, who want to access a creative way to talk about the worlds they see falling apart. Universities, as you might imagine, are full of smart and inquiring minds. But also people, who have to write and teach from their well-honed ‘left hemispheres’. Their access, to the ‘right hemisphere’, to their creativity, has often been blocked, and their knowledge and experience made inaccessible to most non-academics.

So, one rainy day two years ago I was teaching a class at Anglia Ruskin University for a group of academics, and I wanted to talk about voice, how you address the reader. It is very hard to break out of the strict academic position, which demands you justify and footnote every statement you make, to maintain a distance from your feelings, and everyone else. Some of the researchers in the room that day had not even spoken about their work to each other before.

So, to crack some of that institutional stiffness, I took out a cardboard box. I like this exercise, as it is physical and easy to envisage, and if you have a cardboard box to hand, you might like to take it out now too. I developed it from an Arvon writing course Lucy Neal and I used to run for changemakers and climate activists called ‘Fierce Words’, where Lucy, a lifelong theatremaker, would teach people how to access their real or authentic voice when speaking out loud.

The box has three functions, each representing the position you take up as a writer towards the reader. First, as a podium, where you stand on the box, and broadcast your opinions into the air. I believe, I am, they are, you should, we must…as if you are the only person who knows what is going on. The shouty politician position.

The second, as a hidey-hole: where you crawl into the box, and rant quietly from a dark corner. Poor me, no one cares. The suffering silo position.

The third ‘goldilocks’ position, is when you hold the box in your hands and put the best of yourself into it, and offer the words up to the people, as a gift.

Usually I ask everyone then to think about a dilemma they want to transmit, and write a sentence from the three different positions. People get out the notebooks, and afterwards read out loud what they have written. Everyone laughs, as we all expose the self-importance and self-pity of ourselves. But we usually listen to the third version. We’re not moving away, or feeling coerced by the text. We are still and silent, paying attention, receiving. That’s the key.

Reading your own text out loud is always a good test in writing, even if you just do it for yourself. If you can’t bear the sound of your own voice, no one else will either.

What you want is to be able to stand up and sing your song in the forest.

Memory

Birmingham, 2023

The thing is I just don’t know where I am. I recognise the clock tower but these walkways, these new buildings, those trees? I’m heading for the Old Gym where I am about to teach a class for Lucy’s joint art project, Walking Forest. She has written a leafy courtroom play called Ring of Truth about what happens when an oak tree brings the government to trial for not addressing the rising carbon emissions that prevent trees from prospering. The scientists are playing expert witnesses in the case and have to both write and perform their scripts. I am walking towards our borrowed classroom with the box in hand. My task is to loosen the shackles on their imaginations, so they can speak for the oaks, for the soil, for the purple hairstreak butterfly.

I did not expect it would do the same to me, unnerve me in a place I feel I should recognise but cannot. What happened to this university, to those wild rebellious student days, those shabby seventies? Everything feels corporate, and slick. And muffled, heads down everywhere poring over phones and laptops. It was if I could not orient myself any longer.

After the class, walking through the old neighbourhood where I once lived in a squat (now equally gentrified), I remembered the book I had been writing round about the same time I met Rachel and Gemma. It was about our practice of dream tending, and how long-term memory works. The photo memory of places and people, the nostalgic moment, the selfie, is not always the important thing: the seed for the future. That was held in the classes I went to at the time, how I learned to look at history and literature askance, from a Marxist perspective, from a linguistic perspective, as a meta narrative, how I got to question my upbringing and class, and find my radical edge.

Sometimes you have to plough deep to know your own self, to unearth your own flowering, To find conditions that can crack your protective kernel open and allow the seed to germinate. When I was young, the breaking of that seed casing began in the red-light slum districts of Moseley and Balsall Heath, living with fellow students from the working class North; and later when I was on the road in the Americas with Mark, unmoored from conventional life. But germination can also come from the inside. Dreamwork is one way to disturb the monocultural soil, where a memory of otherwise can arrive out of the dark.

The main tech we used in our Dark Mountain creative workshops was all about voicing that original memory and using it as a portal: the first tree that felt like kin, the first encounter with the Earth as a sentient being, a moment when the wind or the water spoke to you, or a myth or fairy tale.

Here is an extract from the introduction to The Earth Dreaming Bank about that kind of catalyst.

And if such memory comes to you, feel your feet, take a breath, and stay with it a while. Allow it to unfurl. If you find yourself with a moth in your hands, let it fly free.

Standing in the garden one morning I had a memory of Venice, only it wasn’t what I would call a photograph memory, a nostalgic looking back at a certain time with certain people. It was a full-scale physical memory of place: of the strong lines of marble, the salty lagoon, a certain kind of sunlight, the first taste of real salami and Italian bread as I sat down, a young English student with my paint box and picnic in the spring by an old plague church, closed for lunch. I had forgotten the place, dismissed Venice years ago. Venice was where, during my twenties, I loved to go each spring to come alive in that early sunlight. To open my eyes and senses, dulled by city work and winter grey.

But Venice was also certain relationships with people that had festered, turned course, sometimes left a sour or sad tone, an odour that I no longer wished to recall, Filed away in a box, like a letter you cannot quite bear to throw away.

This memory was different because there were no people there. It was just myself. It was a total recollection that some part of me had enjoyed, unhampered by any emotional or psychological difficulties. It was untarnished by time. It was a body memory that held in its cells the original sunlight, the original awakenings of all those springs.

Living memory is not a fixed thing like a photograph. It moves and changes. Memories shift around our physical beings like the currents on the sea-floor, revealing different stones and entrances, and at other times burying them in coloured sand. Bright and bizarre fish we do not know the names of swim past us, luring us onward, elegant seaweeds caress our feet. If we are sensitive to these movements and colours, they remind us of other parts of ourselves that do not fit the tales we tell of ourselves to others, that fit the forms we fill in like tired clerks of our clockwork empires. Our official biography, the person that society and friends and family see and know. There is another being entirely, who was always there from the beginning but is never seen, except in moments of intensity by some. Whose sea-changed visage you may also glimpse as you too swim by.

I began to make a record of this secret self I dived for in my mind’s ocean, a self which I would catch in glimpses in dreams, in the shelly salty memories that would appear, like the moon suddenly over city rooftops, and stir inner parts of my being with ancient and archaic feelings, with belonging, patterns that this modern life had no words for. I hunted for those wordless pieces of myself in these years. I learned to catch these memories and savour them, to decipher their mysterious silence, hold them like a moth in my hands long enough to enjoy their fragile incandescent beauty before I set them free into the rich dark night air.

from The Door of Hades, The Earth Dreaming Bank)

ENDNOTE: Lucy came last night bearing a box of the most delicious mangoes from Tooting, and this morning we went to visit the San Pedro cactus in Malcolm and Eileen’s polytunnel. This night-blooming cactus was the subject of the first Red Tent post, Mesa about portals, and probably one of the most influential plant encounters Mark and I ever had. I just wish he was still here to see them flourishing with 40 flowers! (Normally around six). Here you can see some still out, some closing from the night before. They bloom once a year for one night only, so you have to catch them while you can …

Thanks for reading everyone. The Red Tent will be back after Lughnasagh with the third step of The Labyrinth and the Dancing Floor. Happy high summers all!

I love these pieces on the Uneasy Chair! So much to think about for my writing practice and for teaching, where I'm always trying to cut through those formalities and endless restrictions of institutions, and self. "The reader is your friend" - so basic, so simple. Thank you.

Brilliant, Charlotte! Approach the reader as a friend.