We shall by morning

Inherit the earth.

Our foot's in the door.

(from Mushrooms by Sylvia Plath)

In the quarry the mushrooms are gathering under their host tree, the birch, and I am lying on a mossy bank, golden leaves and silver branches above me, red and orange forms beside me: a troop of Amanita muscaria. Dale Pendell1 called this mushroom ‘the most famous entheogen in the world that nobody uses (OK, hardly anybody).’ However, more stories and speculations have been written about its effects than any other species: as the basis of Soma, elixir of the gods, about its alchemical role in ancient cultures from Greece to Afghanistan, about the battle frenzy of Vikings, about Siberian diviners and their flying reindeer that transport you deep into fairy tale realms. But no matter how much you might want to unearth the mysterious and compelling nature of this ‘scarlet woman’, fly agaric is a formidable being to put in your mouth. Its consequences are not for the fainthearted. Unlike say the psychedelic exuberance of the tiny liberty cap, its psychoactive effects mean you’re mostly sleeping and dreaming, sometimes for days, and drooling (apparently). And heaving. A lot. I’ve never eaten one, but I once took one home and slept beside it and had an extraordinary dream: a small being came striding across the universe shouting: your mother has made a right mess! Alphabets were streaming out of his mouth as he roared past. The only letter I could grasp was shaped like a twiggy Y.

The quarry lies on the edge of the territory where I go with my notebook. Millions of years ago it formed part of a seabed, and there are whalebones amongst the flint pebbles, rounded and oblong shapes that lie on the heather and lichen-covered floor. The industrial extraction for sand and gravel has revealed the bones of the land that are stacked in layers: an amphitheatre and treasure hoard for geologists and metaphysical seekers in deep time.

The slopes of the quarry are bounded by scrub: and it’s here, under the trees, where l am trying to remember when exactly the newly named kingdom of ‘funga’ first appeared in our sentences. Sometime after the financial crash of 2008, as carbon emissions rose and the consequences of a fossil-fuelled lifestyle became apparent, the phrase mycorrhizal network began to pop up among the activist responses to these forces in a fast-growing grassroots media. The phrase made sense of this collective underground resistance to the ‘business as usual’ model, connections between future-thinking people the were happening under the radar. Mushrooms themselves started to appear in lion’s mane wellbeing teas, turkey tail medicine, in radical oyster and reishi mushroom farms in cities. Suddenly we knew about hyphae fusing and branching underground, the flora of our microbiome, as scientists realised that trees were communicating with each other by a wild wood web of mycorrhizal fibres. By this century’s 20’s everyone was entangled in the kingdom.

Once you find one, you see them everywhere.

The metaphor suited future-looking progressive circles partly because the ideal of ‘community’ was a tricky beast to handle. The word conjured warm feelings of belonging but the reality was something else. Partly because place-based communities – those neighbourhoods and villages many of us had left behind – proved to be deeply conventional, and resistant to change. But also because ‘weak links’ made in most online or campaign-based groups made it easy to leave. No one would miss you.

This is however the nature of networks. These movements appeared, they burst their spores into mass consciousness, they deliquesced dramatically and disappeared from view. The mushroom metaphor fitted the bill far more accurately than community. The mushroom movement could pop up seemingly out of nowhere and be everywhere: it had potency, edge, it looked unusual, even gorgeous; sometimes it tasted good. And you could rest secure in the knowledge that actually the mushroom was only the fruiting body of a vaster organism: the mycelium was the thing that mattered, networking away in the dark. We were all doing our bit you could say to yourself. One radical hypha at a time. And sometimes this was true.

But here’s the thing with that handy metaphor. The mushroom-in-reality doesn’t work on its own, to make itself feel important or loved. It doesn’t sit in a circle and ask you to share your feelings. It’s a non-narrative lifeforce that connects the whole forest, it nourishes the roots the trees, it breaks dead matter down, absorbs nutrients from seemingly impossibly sources, the bedrock of the planet itself. It is a peerless exchanger and transformer. There’s work going on for the benefit of life and death and life again.

Is our presence in life doing all these things? Ha! Are we active agents, metaphysically, physically, within the fabric of our days on Earth? Invisibly, for no glory? I didn’t think so.

This is a practice. No one has this down. These gatherings need another structure: something less stodgy than community, less controlling and mechanical than a network, a framework that can embrace now-you-see-me-now-you don’t ensembles and alliances. Something that allows other difficult elements into the ‘comms’ beyond our carefully curated social spheres. Like grit in an oyster. Like a scarlet mushroom you dare not eat.

Shiro

What was missing in those activist meetings was what is always missing: a relationship with the more-than-human, the natural world we are all trying to ‘save’. What was missing was a way of seeing the predicament we are in without trying to save anything. I first came across the concept of assemblage in conversation with the post-activist philosopher, Bayo Akomolafe about his metaphysical work on the transatlantic slave trade. He tell me we can consider sugar cane and its metabolism within human white European bodies as part of an assemblage of ingredients that made slavery possible:

It helps to ask: if sugar was an active non-human agent in the proliferation of that economy, that arrangement of master and slave, then what kind of moves can we make today to make sure that doesn’t happen? Then we talk beyond just active legislation, or healing people of their evil. We talk about meeting sugar cane, the idea that we are framed in unmasterable fields and forces that go beyond the liberal humanist project. Framing it as something that is more than human.

By seeing any predicament as an assemblage, other kinds of awareness apart from moral judgement come into play. Possibly the most dynamic exploration of this mycelial approach can be found in Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s The Mushroom at the End of the World. Subtitled On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, it’s an anthropologist foray into the precariat economies that have sprung up around the Japanese delicacy, the matsutake mushroom. This powerfully flavoured mushroom is symbiotic with woodlands in a state of human-caused decline, with pine trees in particular, and has flourished in recent years in the depleted forests of Oregon. Here it is harvested by bands of foragers and sold to markets in Japan where it no longer proliferates due to the decline of satoyama (or peasant) silviculture.

The inter-dependant relationship between tree and mushroom cannot be replicated however by human hands. For distribution it depends on a mycorrhizal network of correspondences that connect refugees from the war zones of South East Asia at one end with an ancient culture of gift exchange in Japan at the other, set within a global capitalist system that collects, ships and markets the mysterious mushroom growing in Oregon as a commodity.

Tsing’s master study looks at this as an assemblage of many factors, including the character of the mushroom itself that, like the equally prized European truffle, fruits underground and requires skill and memory to track. The mushroom challenges an industrial mindset that only understands life in terms of human control and profit. The Japanese place-based studies of the local ‘shiro’ (mycorrhizal mats) were ignored by US researchers, as they did not consider scale. Their attention was on the mechanical linear and square shapes of the timber industry that could be imposed anywhere, not the many-levelled intricately connected living medium in which a matsutake mushroom flourishes.

To find other ways of being, to flourish in the ruins, means first thinking not along different lines but from within matrices of complexity in which human beings form a strand. This attention happens when our minds are not looking for universal principles to apply, but for collaborations with the more-than-human worlds at our feet. Engagement with local ‘shiros’ in our own territories are what make this kind of collaborative thinking possible.

Our rational minds, like the US Forest Service, do not understand anything that cannot instantly be scaled up. Thus, one small quicksilver shift in consciousness is dismissed as ineffective because it cannot be applied to all things immediately. We look for the big solutions, the individual heroes and leaders who will save us from this mess. We forget we have a capacity, are hard-wired if you like, to work in assemblages. We are not a solo act.

Breaking down old forms

Mushrooms appear in their manifold forms as the year goes into fall, and if we were smart we would pay more attention to their less admired characteristic: that of breaking down matter. As autumn cedes to winter, as the brackets appear on dying birch trees, everything focuses downwards on feeding the soil and the roots that feed all creatures. I want to be good compost, I heard the poet and ecological storyteller Sophie Strand tell me, and was startled by her capacity to regard her own physical collapse in such visionary and generous terms.

However most of us resist the fall in our individual lives, and even more the fall of our culture. And yet here we are, leaves turning and falling and mulching down. We have been taught to see decline as a failure, rather than a natural relinquishment that nourishes the world. The maintenance work of our maturity as people differs radically from our prized spring and summer, and if you follow the cycles of the year, you realise that the approaching winter ushers a time of letting go and regeneration, and that mushrooms are the heralds of that process.

The poet and activist, Gary Snyder, once wrote that in a fully mature oak or rainforest, a high percentage of the energy is not gleaned from the living biomass, but from the recycling of dead matter – dead trees and animals – that lie on the forest floor. This ‘detritus energy’ is liberated from these dead forms by the transformative actions of fungi and insects.

As climax forest is to biome, and fungus is to the recycling of energy, so ‘enlightened mind’ is to daily ego mind, and art to the recycling of neglected inner potential.

Transforming old thoughts and feelings, composting the past in this spirit becomes the life-energy that fuels our present lives. In this individual creative writers or artists act like mushrooms within the collective. We liberate energy from what is dead and give energy to the living, and thus become symbionts rather than parasites within the consciousness of the Earth.

The predicament for those born into Empire is in still looking for the upswing when the story we know by heart is over. The grand narrative of our peaks and conquests, our civilisations with their architecture and technological wizardry, can no longer be offset against the reality we live in. The physical violence on which ‘progress’ depends is being increasingly exposed, like the stony walls of this pit, and the consequences of its superhero plot felt in every weather system on Earth, in the air we now breathe, in the water we drink. The story of our deliquescence however, is not being told, because, though we may know the facts, we live in a culture that pretends we can carry on on an uncalm planet. We are entering a state of collapse and still reading Jane Austen. We might move in progressive circles but still champion leaders and role models, cleave to noble ideas of justice and fair play, when it’s clear the captain has no intention of turning the ship around.

To change those rigid old-school ways of thinking we need to go to the masters of transformation and breakdown: our non-human helpers. We need to think like a mushroom. Because those human heroes and ideals are not going to save the day. We need to speak with the Earth in its own language, and know how still to find beauty and meaning in precarity, to flourish among the ruins. And if this series is about a metaphysical practice for facing collapse, this starts with another way of seeing the world: listening differently, finding alliances between species, allies in surprising places, assemblages outside the established forms of family and like-minded people we say we ‘like’.

And most of all learning to how to mature and let go.

Fugue

Perhaps the final and most startling lesson mushrooms teach is polyphonic awareness: an attention that happens when you listen to a polyphony of sounds rather than a single dominant voice. The classical pianist Glenn Gould in his second recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations looked for a framework that would bring the variations together. In the debut recording that made him famous 25 years earlier, he said the 30 pieces all went their own ways. In this later version, made a year before his death, he would give the variations a sense of continuity in terms of tempo. His rhythmic structure did not follow the relentless tick of the metronome however, but was processional, the end of one variation becoming the timing for the next, so that each folded into the other.

It’s said that when music is played to them, plants respond most positively to classical baroque and J. S. Bach in particular. Why is not known. Possibly because baroque is a style of music which is polyphonic, which means different strands of music, rhythm and melody, harmony and dissonance, entwine with each other. Like the plants in a forest, like the entangled Earth, creating a pulse that brings all variations together continuously.

We think like a mushroom because sitting here, you can absorb all the sounds and colours of the quarry at once. You are not a predator looking for prey, you are not lost in thought, or sorrow, using the Earth as your backdrop. You are practicing living in a contrapuntal universe, as an assemblage, where being human means acting as one kind of timekeeper among many. The mushrooms don’t unify within a single melody, or a thumping base beat; they don’t have leaders, or hierarchies. They appear in circles and troops. A comedic ensemble. There is no one left dead on a tragic stage when they have disappeared, only the shape of a dancing ring in the grass. You feel them invisibly in the pulse under your feet, as your bare feet walk across reindeer lichen, as you lie on this mossy bank on a sunny autumn day with the robin singing his aria in the furze. The rhythmic structure of the planet in a multitude of interconnecting variations.

There were mushrooms at the beginning of this metaphysical enquiry, as there often are. Appearing at the edge of our modern lives when we were open to experiment and revelation: a time of voyaging out with a merry band of companions, whooping and hollering in the woods as we encountered a living breathing speaking planet, ourselves as libraries of knowledge in time, part of its extraordinary lexicon. The mushrooms lent us their hyper speed, rocketing us straight into the consciousness of the right hemisphere. But only for a few hours. Most of us forget how that intensity felt like home. But if these times are not stacked away, filed under youthful folly, you can still access the planet’s deeper mycelial intelligence; you can learn its language, translate it into clumsy linear sentences, remembering why at the start of most cultures somewhere (usually hidden) you can find a mushroom. And then an alphabet.

Your mother has made a right mess!

Six mushrooms steeped in honey pounced on my thirty-something city life like a jaguar in the Yucatan and carried me back into the forest. Not so much opening a door as breaking down a house. After Mexico, mushrooms appeared as gifts from Oregon, in muddy fields in England, in plastic Tupperware from Amsterdam on a Norwich market stall while a legal loophole allowed their sale. Then they disappeared.

By that time however, I had grasped enough of their grammar, to script a practice of working with dreams, with plants and places and planets, a way of holding a metaphysical dialogue that underpins this series. Only now though, decades later, do I find the interconnecting links between those explorations to build a framework. You think it is the mushroom in your hand, but of course you forget, it is the mycelium under your feet. As many connecting threads as there are stars in the sky. You need the skills of remembering to sense them in the dark. Writing is one of these skills, walking in twilight, becoming animal, sitting alongside trees in your territory is another.

Maybe you took those mind-shifting mushrooms once on a starry night and looked up above you and laughed, because suddenly everything cohered, made sense: the world, the universe, you, the people, here, now, always. Maybe you looked up and had the same moment, sprung from your ordinary life by the immensity of the desert, or ocean, by a sudden loss or solitude. Maybe it’s time to remember those seemingly random moments of an earlier time, and revisit them years later with a mature eye. Find the rhythmic structure. See another pattern that is continuous. What will hold us up, take us through. Keep the pulse going.

Spore

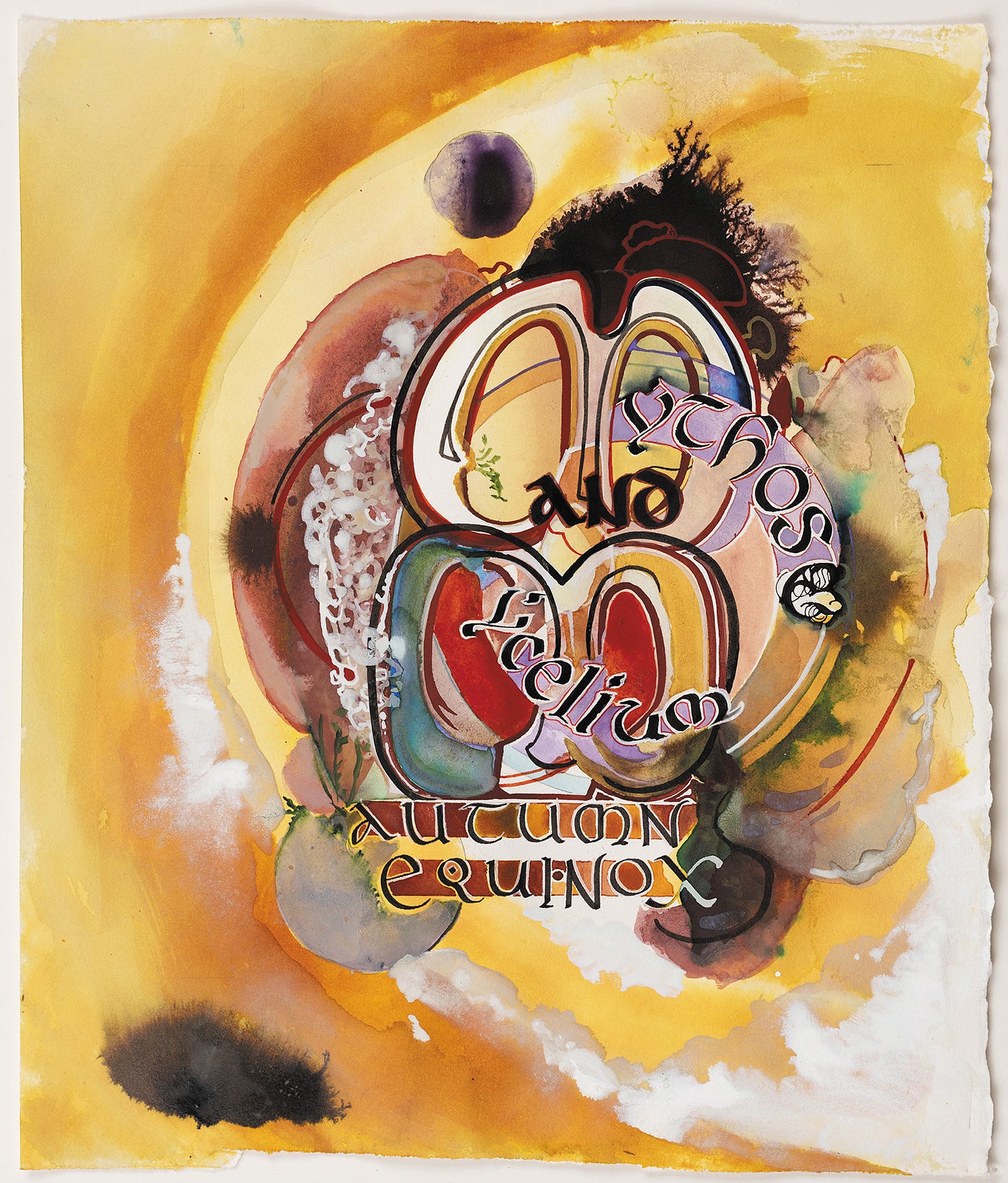

I’m very much looking forward to working with the Eight Fires assemblage next month in our Dark Mountain’s Winter Sessions. We’ll be gathering to foster a creative land-based practice for the year, centred around the fourteen days of the Halcyon Days (more on this in the next post). Here meanwhile is a piece I wrote for the new issue about our ‘Mythos and Mycelium’ practice Going Under, to introduce the Autumn Equinox section. Happy hyphae all!

Thanks for reading everyone and hope to see you again soon.

If you would like to read further about mushrooms and working with plants, you can find more in my book 52 Flowers That Shook My World (PDF). Paid subscribers are welcome to a free copy if they sign up.

1 Phamako Gnosis by Dale Pendell (see Red Tent Shelf: Mesa)

Very inspiring

This was so so wonderful. So rich with ideas of relationship and nourishment for thoughts about what I am to become now that I’m entering the last quarter of my life. I’ve shared it with several friends. I’ve got mushrooms popping up and deliquescing all around my wonderful garden in Sebastopol, Northern California. Thank you so much. 🍄🧡🍁