Hello dear subscribers and readers. I’m afraid this post is arriving rather later than hoped, as for the last month I have had my hands full editing two Dark Mountain books. But, as promised, here is the third instalment of The Labyrinth and the Dancing Floor, the crux at its deep centre. Everything in this journey leads up to this moment, and everything afterwards – the return against the flow, the exit and celebration – is shaped and informed by this core encounter. It begins at the end of summer by a tree that grows out of the shingle on the Suffolk shore.

The bull we have always known – he was the first we painted on the cave walls and fashioned in stone: as auroch, bison, buffalo. When we stand beside him we can feel him in the dark, his warm breath, his creaturehood, his presence. We don't want to be anywhere else, even though we are mostly mute, enthralled and also terrified.

If I give you kinship with the beasts, he says. What will you give me?

(from ‘The Red Thread’, After Ithaca)

There is a stretch of shore we used to go to at the end of summer. Bare dunes, a luminous sea, a shingle beach with the ragged leaves of sea kales and poppies, and a gnarly apple tree sunk deep among the stones, miraculously hosting sweet fruits. It is by this remnant of a lost orchard that Roger Deakin ends his seminal book about trees, Wildwood.

It is a place of endings. Around this tree are the waving forms of common wormwood, famous vermifuge and star of Revelations, and a key ingredient of the vision-inducing absinthe. Oscar Wilde, writing about the ‘green fairy’, said after the first glass you saw what you wanted to see – your grand illusions; after the second you saw things that were not – all your demons; after the third you saw what was really there, ‘and that was the most horrible of all’.

When we had come that late summer at the turn of the millennium, these dunes had welcomed us home. Our travels ended here. It was the first time I had met this wild artemisia in my native land. I put a silvery leaf in my mouth, and winced. Wormwood is the bitterest plant of the British Isles. The active principle of all sun plants is not sweet, as you might expect, but bitter. Bitterness and light are what drives the sugar-loving parasites out of any living system, including our own. Bringing death to the pleasure dome that has up to this point blinded you from what is really going on.

Sacrifice

The classical story of the Minotaur imprisoned in the Labyrinth is well known. The hybrid child-eating monster has to be slain by a solar hero and the princess rescued. In the original Minoan version however he is celebrated as the initiating bull of Venus. He who bequeaths knowledge at a price: the death of your former life.

The moves in this Labyrinth practice are mostly out of stuck places, slipping Houdini-like out of mazes and puzzles set by the trapping mind. But this second step is particular: it is about being still, not moving, the moment when you turn and face the Bull, allowing the ripened plant that was you to be trampled, for the chaff to be blown away and the seed revealed. To undergo what Gurdjieff might have called ‘the terror of the situation’, our existential dilemma as mortal beings, when the veil between dimensions is lifted and you realise what life really demands of you.

Before you were always blithe about death, in a wild youth of physical daring, laughing like a child on a high wall, but this feeling of spiritual annihilation at the core is quite other. It’s happening in a realm you cannot name but in this moment utterly understand. You feel its presence bearing down on you, squeezing what you think of as life, out of you.

The mind fights the existence of this dimension at all turns, and to endure it, we have not to move away, or control the experience. The modern world loves to use myth as an entertaining story but closes down when the myth reveals its alchemical demands for transformation. People back away or say they don’t understand what you are talking about. Myths challenge the fairy story of civilisation, the mind’s domination, and every trick will be used by yourself and others to pretend obligations to life do not exist. We might say our physical death is a payback for our earthly life as a biological ‘fact’, that ‘none of us get out of here alive’ and laugh. But that reality is quite another prospect when your soul is facing the cosmic bull with eternity all around you. When you realise there are consequences to what you do here on this Earth when you leave.

One of the gifts of the bull is to learn how hold fast, keep your feet on the ground, connect with your heart. Not move when everything in the room, in your life, tells you to. He is the primordial teacher, as the wall of any Neolithic cave can show you: his greatest lesson that knowledge is embedded in form, in the magnetism of physical presence.

When Mark invited people to step into the world of plants, it was to make a connection with the spirit of things. Inhabiting this central core was the dancing step he taught, learning how to be anchored and radically relaxed in a rocky time: with sea kale roots in the shifting shingle, to hold many things and be utterly stable like a neighbourhood oak. Because he had those qualities himself, people felt at home enough to still their restless minds and allow other communications within themselves and their territories to happen. Ostensibly the ‘task’ was just to hang out with plants, but it was also to stay long enough in a plant’s company to connect with the intelligence of the living breathing world. The world we had first made contact with in the forests and mountains of Mexico.

I don’t do much, he would said of his teaching. But you are there, I would reply. You are like a bull in the field. When the bull is there, everything about the herd is different. He is not doing much, just eating grass like the cows. But you walk through that field differently. And this class, this place, this organisation feels different with you in it. Coherence and friendliness and self-amusement are in the room. A door is open where before it was shut.

People would sometimes step though that flower door, and return with joyous accounts of their encounters, or weep, remembering what they thought was lost. And sometimes they would feel a presence, bearing down on them in way it was hard to define, requiring a radical change of heart.

Dreaming of the Bull

I am standing close to a huge bull. Our heads are almost touching. He is enormous, silent, immovable. It is a frosty morning and I feel the warmth of his breath envelop me. As it does my heart starts to pound wildly.

Suffolk May 2004

How does it feels when a hedgehog takes your hand and leads you into the wood? When a grey eagle takes you in its wings into the sky, or the great blue whale dives and shows you an ocean world of frequency?

When the creatures appeared in our dreaming practice years, you felt it meant everything, even though it was hard to find the words. Something that was broken felt whole; some ancestral agreement felt honoured. They communicated directly through their physical presence and the way it felt being with them, experiencing their essence in close-up in a way that was not possible in ‘real life’.

Animals are at home on the planet and their presence, especially the wild ones, gives each place its meaning and vibrancy. This dream was set in Port Meadow, an ancient common land in Oxford where we once lived, where cows and horses still graze. The bull is as much the spirit of that place, as he is himself. My heart is still beating with excitement as I wake up.

The human heart longs for kinship, to stand alongside the great beasts, in a world where we are all in connection. This is both a longing for a world before it was built over and machine-dominated and also for a world where our own physicality and animal emotions are valued. Unlike the mind which sees animals as food or entertainment or symbols, our hearts recognises every creature as a planetary fellow.

The animals come to remember us. Our own lack of presence and ability to move allows the heart to be dominated by the mind, so they come to remind us of these things within ourselves. I am light as the bull is heavy. He is providing clues as to the energies my heart needs to muster in order that I can hold my own. I am not like a bull, so his strong large presence, his warm breath, his immovable solidity are things I have to learn, in the same way I ‘learned’ to fly and swim with the bird and whale.

Animals affect our hearts in ways it is difficult to describe. Unlike our fickle minds, they are straight and true with us. It is remarkable how gentle the bull is, how all creatures are like this in dreams, whereas almost all human beings are antagonistic. They restore some kind of nobility in us and bring us back to an Earth where we can be in harmony. You just have to tune in to their wavelength.

Arena

If you hold fast this is the moment she appears in his blazing eye…

Welcome, she says, to my dancing floor. The hard walls of the Labyrinth vanish and in its place are lines that loop around in an intricate pattern. They are of all colours and intersect in ways you can feel but cannot articulate. There is a hum you cannot tell whether is on the inside of you or the outside of you, it burns like a slow fire through your chest, and the scent of a thousand small flowers…

‘Focus,’ she says, ‘for this time is limited.’

‘Oh, you are a bee!’ I exclaim, ‘And the bull is a star...’

‘This is your task,’ she says. ‘Find your way back.’

(‘The Red Thread from Dark Mountain: Issue 10)

At the end of that epic mushroom journey in the Mayan rainforest in 1990 we find ourselves in a small hotel room in San Cristobal de las Casas. It is a sobering moment. Within Indigenous traditions these encounters might be called an initiation and honoured as such. You would be given a name and a role within the tribe and the landscape where it had taken place. For modern deracinated people that meaning has to be wrested within a culture that does everything to stop those connections happening, where hallucinogenic ‘trips’ are used to cure mental illness or addictions, rather than to meet the powerful alchemical forces of the planet.

Up to this point I have called myself a writer but after the core encounter the definition of your self in the known world falls apart. You realise if you are not ‘there’, embodied what you write, you are a cipher, untempered, taking no responsibility for what you are saying. Your script sits at the end of your typing fingers as if you were not part of it. The Minotaur will not let you get away with that anymore. I was a journalist with a brilliant career, able to be smart and funny at other people’s expense. After this I won’t be able to write that copy. That’s what gets ‘sacrificed’ at the centre, not yourself, nor anyone else but the flimsy construct that was you up this moment, shaped by family and education. You meet your core self and your companion’s and now realise that everything you knew until now is everything you will have to let go of. Including them.

You might ask: was it worth it? The loss of profession, house, lands you loved, the man you loved. And I would tell you: I now know at depth what life is, what it means to be exiled, disenfranchised, bereaved; how nothing can replace the physical presence of someone, or a place. How in spite of everything, the beauty of Earth never palls. And although I have yet to find the ‘reason’ Mark went in the spring it was a destiny with which I cannot argue. That is the bitterness of wormwood in my mouth, the taste of our homecoming, and my own small apocalypse.

Looking back now, I see what we had felt in that damp hotel room, that mountain chill, was an intimation of what the encounter had mapped out for our lives.

Destiny sounds a grand thing, a Napoleonic thing, but the kind of destiny you meet in the Labyrinth is your own as a human being on a planet that is assuredly not human. The moment you relinquish the flower and the fruit to become seed. The seed is tumbled, blown, eaten, abandoned, buried. And then it waits in darkness. You wait in darkness. In the tinge of September air, that’s what you remember, along with the ripeness of all the fruits of autumn, the squash and corn, apples and plums.

In San Cristobal de las Casas, we knew life was never going to be the same. There was no way we could fit back into the box that once contained the people we were.

Mostly, what you sacrifice at the core, on that threshing floor, is your innocence. It’s a relief, but also a loss.

Dreaming of Varuna

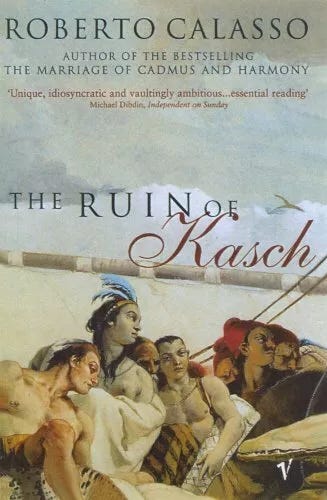

There are two key texts that inform this Labyrinth strand: one is The Rings of Saturn by W. G. Sebald and the other The Ruin of Kasch by Roberto Calasso. Both of these books, Mark kept by his bedside and often re-read. Sebalds’ encounters with the memory of place and the horrors of history (written about in an earlier essay here) follows a real and metaphysical journey through coastal Suffolk, at the core which is his becoming lost in the ‘labyrinth’ of Dunwich Heath. The second is the first of several extraordinary books about myth by the Italian writer and publisher, Roberto Callasso, in which the relationship between civilisation and sacrifice is germane. It is set at the time of the French Revolution when the debate about legitimacy and power is taking place. How do you replace the divine right of kings with ordinary government, what spectacle will bring the people together?

The title comes from a Sudanese legend about an ancient kingdom based on the periodical sacrifice of the king, One day a stranger arrives and the power of his stories is so overwhelming that the priests forget to look at the sky in order to decide the right moment for the ritual. So their regime is overthrown. However this era doesn’t last, because Kasch is invaded and the new regime collapses.

The book explores how the loss of ritual and obligation allows modern rulers to do as they please, and although that loss may make people’s lives easier, it invariably leads to meaninglessness and ruin. Immersed in Calasso’s labyrinthine text you start to see how those who now govern justify the ‘sacrifice’ of young men and women, animals, trees and whole territories to feed the war-mongering monster of civilisation and bolster their own position; how ancient ceremony instead demands the sacrifice of worldly power to the greater world of the spirit that contains it. The fire of sacrifice acts as a bridge between the dimensions and keeps the balance between the two.

In 2013 I write about a dream I once had when the Indian god Varuna visited me:

‘Black-coated, stern-faced, he strode down the aisle of a church and delivered a message:

Consolable grief we can help with, inconsolable we cannot, with the underlying information that separation is arrogance.

Varuna is a primary, underworld god, ruler of the watery nagas, who carries a noose in his hand in the shape of a snake. He storms through the dark church because he is the keeper of the cosmic law, which is not the law of human beings or their religions. In The Ruin of Kasch, Calasso outlines the relationship between the primordial god and his worldly counterpart, Mitra:

The civilising sweetness of Mitra, ‘everyone’s friend’, can only exist insofar it can stand out against the dark and remote background of the sovereignty of Varuna. ‘Mitra is this world, Varuna is the other world,’ the Satapatha Brahamana clearly states. Mitra is the world of men; Varuna is the rest, perennially around it, capable of squeezing it like a noose.

When the world only runs according to the laws of social contract, Varuna’s nooses tighten around ‘those who did not know these were the results of many sentencings under a law no one could decipher anymore’.

Varuna comes before Indra, before Shiva, before all the monotheistic gods and the myth of the Fall. He is akin to the classical Titans, kept trapped under mountains, in stone towers, or banished to the oceans. But no matter how invisible these primary beings are made out to be, there are consequences to ignoring their ancestral laws. And a life lived knowing there are consequences to every action takes a very different shape to one that assumes, so long as Mitra’s laws are kept, you are free from any feedback loops.

When I had the dream it was the word console that grabbed me. It means with soul, with sun. The gods can console the human being, Varuna tells me, but if he or she is inconsolable, this is not because the god cannot help, but because human arrogance will not let the spirit in. If you insist on separation and sorrow, you block the gods’ entrance.

Can I ever be consoled?

I am on the beach, looking towards the sun on the horizon. What I didn’t write at the time was that Varuna was wearing Mark’s coat and had his face.

Thank you everyone for reading this post. The Red Tent will be back at the end of the month to celebrate the autumn equinox when this series first began a year ago. Hope to see you then!

It’s so helpful to hear this backstory to the Minatour and Labyrinth, Charlotte.

Dartington 2023 was a big experience for me and, with hindsight, I can see how that week gave new energy to changes that I was moving through.

The session with Mark did open a door for me and, since then, my path has opened up in so many unexpected ways.

Organising the whole week around the Minotaur and Labyrinth created a fascinating world.

Enlightening as it is Unraveling! The absinthe mythos bleeds throughout your prose here! That loss in the stillness- I see as a grander creation than any other I imagined before.... as to story : Healing chronic illness - IBD (Colitis) in June I had to 'exit life' for a month of recovery from a severe flare up. This period, I truly faced the returning stillness required by my Fate-Will - as I lay, staring at the ceiling , staring at the dark-closed-eyes - it was all I was for days and hours on end... yet, that labyrinthine depth (with surface body)- as I returned to the navigated world again - I know I was reworked in a way that 'I could not see' - albiet, with what was very real 'by me, of me, for me'. It was subtle. A suckle at the blight of more loss - to replace the whole essence over again...