Hello dear Readers, This is the fourth post in The Uneasy Chair sequence, where I share some insights about writing as a metaphysical practice embedded in a local territory. The first intro post took place in winter on a clifftop and looked at three existential positions a writer takes; the second, ‘Undertow’, at the territory of alchemical writing before a spring tide. The third ‘Voice’ was set in a field of rainbow weeds in high summer, and considered the relationship with the reader, and with the force of memory in a forgetting time. Today’s begins in a spiky tunnel of sloes and rosehips, as I cross the marshes on the way to a sweet chestnut grove, where the last winds of autumn blow their golden leaves to the ground. Like the others it comes from the collaborative non-fiction classes I once taught and also from in depth ‘kiva’ work, about obligation, and creating a narrative thread so you might find your way out of the Labyrinth.

‘There is a crow who sits on my shoulder,’ said my lawyer father. ‘It is my conscience.’ And then he stared at his shoes in despair.

When he died, the crow came to me. You have to tell me everything, I said. About conscience.

The crow sat in the corner of my room in the travelling years when I lived on the edge of small towns in Europe and America. Silently, he observed me write my notebooks. And sometimes I would ask him a question. And he would put his head on one side and peer into the mysterious darkness of the void and declare what great law of conscience he located there.

You have to deal with the files with your name on, he said, and leave the rest.

from ‘Temescal’, After Ithaca

The tunnels lead though the marshes: spiky rose bushes shaped by the sea winds that blow through the golden winter reeds; their entrances beckon like zeros, portals into another Earth. In spring, the blackthorn tunnel puts on a wedding dress of flowers, in summer, the dog rose becomes an arbour of bees, now in cold November their fruits dot the lichen-covered canopies, black sloes and scarlet hips, startling against a blue sky. The hallways are swooping with cackling blackbirds. You too can suck the tips of the hips, now tempered by frost, sweet. succulent, intense in your mouth.

At the end of the tunnels, the track opens out to the full breadth of the reedbeds, and takes my breath away. As it always does, as you emerge and see the whole land opened up, light bouncing off the water in the dykes, the vast sky above your head, the sea’s rim on the horizon.

I didn’t want to walk, not really, there is always too much to do, and it’s cold out there and the path is impossibly muddy. But a writer whose piece I was editing had recommended going on ‘long contemplative walks’. And against my worst nature, I went.

‘This doesn’t feel very contemplative,’ I grumbled after two hours of muddy track, and swore as I hit my head against a branch of a stout tree. Of course I knew it was too late for chestnuts, but I kicked the leaves beneath it anyway to see if there were any left. When we lived near here, Mark and I would come to this grove every November to find some to roast and eat by the fire. He loved these big oak tribe trees.

Foraging for sweet chestnuts was the subject of the first post we published for This Low Carbon Life, a collaborative blog a group of fellow ‘Transitioners’ began in Norwich in 2009 to record our everyday experiences of deliberate downshift. It transcribed that moment when you shift your attention from your busy mind to what lies beneath your feet, and realise that the Earth is bountiful and nourishing, even in a city park. In our grassroots years, the generosity of nut trees (walnut, hazelnut, chestnut) became signature trees for Transition. And it was here, in this marshland grove one day, we took an academic and a psychologist to do a tree ‘visiting and dreaming’.

They had come to our ‘Heart and Soul, Art, Culture and Wellbeing’ group to study us and to offer their professional help, while we got on with the business of energy descent, and each other. What become clear, as their minds struggled with this heart-based plant practice, is that you can only connect with the planet, to your soul and others’, if you are prepared to go through the tunnel of thorns yourself.

Writers need material, physical experiences, to write words that strike true. You have to write after the discomfort, the struggle, the sweet taste of rosehips, the feeling that at the end of the track, the world will open up before you, a land of light and air. It needs to matter that you write the journey as testimony, as a way marker. Otherwise what you write will lack desire, fortitude, and most of all fellow feeling, and thus real communication. You will be using other people’s experience, rather than your own, to make a point, and unbeknowst to yourself, adding to the shadow of the world.

As an editor, or reader, you can sense this immediately: does this piece come from a writer with mud on their boots, or in slippers in an armchair?

On mice and men

It was pausing at the roots of this stout tree, I remembered a ‘long read’ I had just come across about John Calhoun, an animal behaviourist. who constructed a ‘mouse utopia’ to study the effects of overcrowding on rodents. His work was ground-breaking in the 1970s but has since been ignored, his use of poetic ‘right hemisphere’ language now deemed unscientific and unmodern . What grabbed my imagination in the article were two phenomena that came out of that three-year experiment and how they explained something key to understanding attention in contemporary culture.

One was the concept of ‘behavioural sink’, which occurred once ‘Universe 25’ had gone into decline, when the seemingly perfect conditions had become an overpopulated prison.

At the most general level, a “behavioural sink”, Calhoun argued, was an “attraction to one locality to assure a conditioned social contact”. That attraction could lead to a “pathological togetherness” in which animals needed to be near others, even if the consequences of such togetherness – eating at crowded feeders when more food could be obtained elsewhere – were negative. Once a behavioural sink was in place, “normal social organisation …” he told the crowd, “breaks down, it ‘dies.’”

The other was his observation of The Beautiful People. These were the mice that spent their time grooming themselves and eating and shunned all social behaviour. The Beautiful Ones, Calhoun said, were ‘capable only of the most simple behaviours compatible with physiological survival’.

What has any of this to do with writing you might ask? In the previous Uneasy Chair post there was an exercise called The Box which shows three ways a writer can engage with the reader. One to avoid is to write with the box over your head, so you are stuck in your own world. This position demands that a reader enter your solipsistic imagination and gets equally stuck. You may be beautiful, your prose may be beautiful, but yon don’t care about anyone apart from yourself. You abandon the reader to suffer the same state. Likewise, when expanded to a silo group, your attention will be shaped by your desire to be in a ‘community’ of like-minded mice, even to the detriment of the whole ‘universe’ and yourself. It will become a sink.

So a good question to ask as you sit uneasily before a blank page: what is your writing actually doing in the world, for life? What are we giving?

*

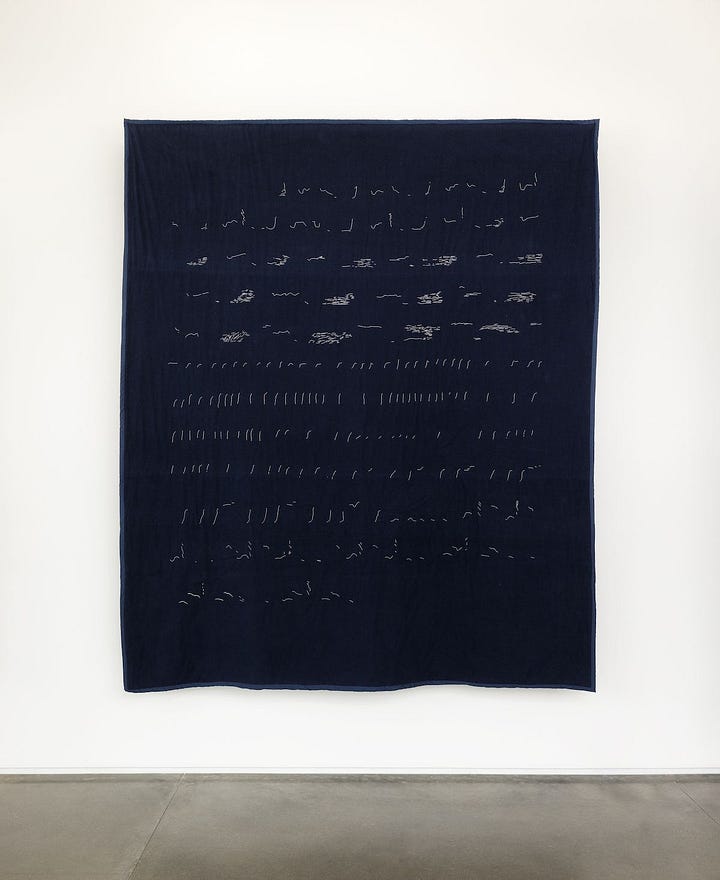

This post is called ‘Ledger’, because everyone in civilisation is born with one, a long one in this age that ancient seers called ‘the time of the dog’s throw’, when you are destined to lose the game, and never be on the right side of history. Writing is one of the most effective tools to contact and deal with ledgers. These record the Underworld obligations that you are never taught but need to seek out for yourself. To call them ‘karma’ or ‘sins of the father’, puts a cultural and moral spin on something that is neither. These are energetic forces you inherit from your family, from your culture, profession, city, nation, gender, race, religion, that have to be looked at, transformed, released, atoned for. They cannot be dealt with by psychology, or political ideology, nor do they fit notions of justice or equality, or any of the righteous mass market terms we like to whirl about our heads like small axes. None will deal with these tasks of attrition. Each ledger is tailor-made.

The beautiful people gazing at themselves, those hanging around convivial feeding stations will not be looking at the forces lying beneath the manic mice-movements of the citadel. Their attention is elsewhere, stuck in repeat behaviours striving to make themselves feel OK, to be seen as worthy and good and meaningful. To find them you have to have a writing practice that goes beyond safety and comfort, beyond playing with adjectives or to the gallery. You have to wrestle yourself in a crucible, go into your dreams, into myth, to sit alongside spiky awkward plants, speak with people you don’t want to speak with, go down streets that make you shudder.

No one can tell you where you need to go, only you know what feels right. Writing is a tool to unearth that ledger, buried as it is under generations of broken promises and disconnection. One way to wrest a key beneath a pile of apparent rubble.

Finding the thread

Narrative is an overused word these days, partly because the story of progress our lives are framed by is fraying against the harsh realities of the ‘metacrisis’. Many of us are trying to find a thread that makes sense of our fall, our part in a show we don’t yet have the words for.

What we need to know is that a large part of ourselves, that part that seeks out the comfortable places, doesn’t really want to find one. Because instinctively we know it will entail what the modern seer Gurdjieff once called ‘conscious suffering’. No one signs up for suffering willingly. It’s not the kind of suffering you can offload on friends and therapists either, because it’s happening in a realm that civilisation has no terminology for, even though we all feel it. The constriction of invisible bars around us, held in place by terror.

But if you don’t have a thread, a intent to go through difficulty, you are always be fighting to stay above, be in control of the situation, or underneath, disabled by it. Having a ‘frame’ for descent give you the necessary courage and awareness to go through and navigate the challenges, particularly the social ones. I once had a Transition frame (community downshift), and then a Dark Mountain frame (creative response to collapse), both of which informed my life and enabled me to meet others on the downward path. But neither of these really cut the mustard when it comes to metaphysics: to the individual destiny of your heart and soul which awaits Maat’s feather and her weighing scales.

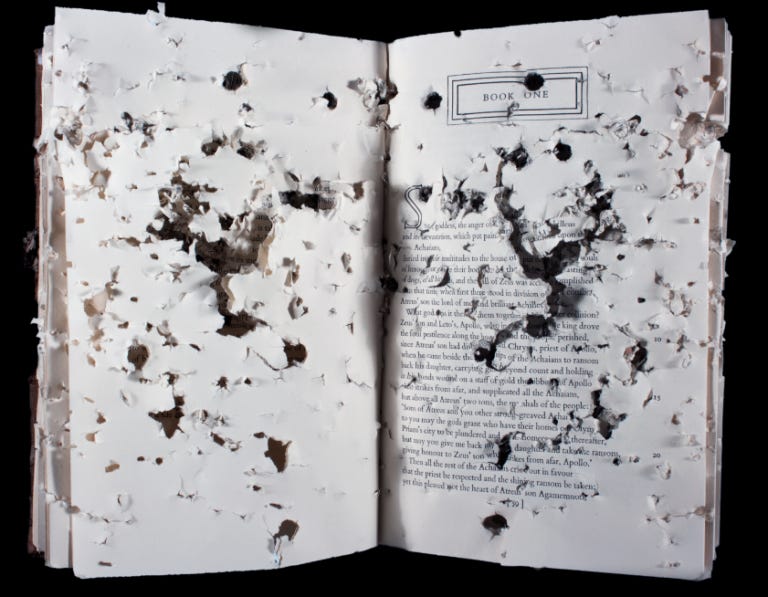

What matters is that you know is that such a thing as a ledger exists and that when you find it, you realise a work is required; that this time the buck will stop with you, that you don’t just do the work for yourself. This awareness creates a whole different frame for everything. You are no longer an arbiter of the world, the mythologist of every lifestyle move you make, you are a prisoner, who is condemned for a crime you did not personally commit: for the brutality so-called civilised ‘people of the book’ have wreaked on the land and its inhabitants: human, plant, animal, insect, microbe. These are the things you have to account for, that come through your small life, your petty grievances, your own body, rebelling in its mute and furious way, against what was done to all people by people and the vengeful gods they have worshipped through millennia.

The struggle of the prisoner is to find their voice: it is hard to hear and you have to listen. When the prisoner speaks it is as if behind an iron mask, muffled, sometimes incoherent, and frequently terrified. But it is there. Only your own heart can hear itself speak. Only the tree, the myth, the river beneath the river, can tell you what it is saying, can teach you to understand its language.

This is the practice that can enable you to undertake the third step of the Labyrinth and the Dancing Floor: the return. To get out of the Labyrinth you need a thread. Writing is one way you find it

Entering the kur

When you die, you leave a paper trail behind you, a long one, and if, like Mark, you were once the scribe of practices, keeper of records, the tax collector of receipts, the house manager, you leave behind boxes of papers. Last month I tackled some of them winnowing their contents, keeping only what really matters, what can be stored as a nourishing memory (because if I don’t do this work, who will?)

In his room during the cold snap, I surveyed our whole lives laid out in piles of paper across the floor: electricity bills, phone bills, council tax records, receipts from railway station cafes, ticket stubs. Occasionally, I would come upon a multi-coloured painting Mark made in our South American days, a photograph of a kitchen with French windows (the lilac fully out in the garden beyond), or a poem, written on a bus, or the start of one, a quote from a man who came to our door fragrant with honeysuckle one May with a clipboard.

Life is like party

That was your Polish mother

You are like sunshine

That was you

Sometimes you dance closer to people than others.1

And I would pause and remember that day, that house, that party, that time we were there, when you were there.

So many days we live in, so many afternoons, weathers and places.

Parking is a problem in Southwold.

One of the papers I kept was a flyer for a performance we gave called Divesting for Beginners based on the myth of the descent of Inanna (Venus) into the ‘Great Below’. When we were working on it, I went to the British Museum and stood in front of the glass cabinets of the Sumerian collection. Among its amulets and seals are held the earliest known forms of writing on slabs of clay.

Only a few of Sumer’s unearthed tablets are inscribed with poems and songs in praise of the goddess of Earth and Sky and her companions. The rest are all accounts, exchanges of goods, ledgers of profit and loss, painstakingly recorded by scribes with reed pens. At the time, I was investigating how an ancient myth about a deliberate journey into the Underworld could make sense of our modern dilemmas; to know that through the challenges of its seven gates, there are also helpers, that there is an exit, that you will suffer and hang on a hook for three mythological days (a long time). That you will have to divest a lot more than fossil fuels to atone for what you stand accused.

I did not notice the accounts. And perhaps it would have been wise to.

Because if our accounted lives are 90 per cent admin, our toil for the rulers of the marketplace (all evidence destined to be recycled or burned), what of the remaining time? What account is there? When do we do our existential tasks, get to experience this Earth and give back to it with our creative work?

Only by immersion in the Earth’s elements, its creatures, plants, winds, waters, light and darkness, can we hope to make sense of our lives here. The planet speaks another language than our dominator tongues, and we have to train our hearts and senses to detect its patterns, beyond the chatter and control of the ‘left hemisphere’ collective mind, its power drive for facts and scientific proof.

That’s the pivot I wanted to introduce in this post. Not so much a method, but a decision. That moment when you decide to head back upriver against the flow: to take up a practice and go out into the cold, make a connection, come what may.

The Tasks

How do we get beyond the feeding station and staring at our selfies on social media? Sometimes you need a structure, a reason to go out of the door. You see, no one actually wants to go out into the cold, and then, damn, have to create a piece of work, and not only that, to then have to speak it out loud to a room full of people you don’t know. On a Zoom call. In three minutes. But here you are, having signed up for ‘the tasks’. Or rather 16 people have signed up for them and you are giving the instructions, promising that you and your fellow ‘teachers’ will also be going out there undertaking them at the same time.

This month I am co-producing an online course for Dark Mountain, based on our 2024 issues on Land and Sea. Called ‘Journeys’, it sets out on four imaginative encounters with our local territories. In this week’s introductory session, the walker-writers brought ‘objects’ from their wild and feral neighbourhoods, ranging from the snowy wastes of Alaska to the rocky Atlantic coast of Portugal, from the wetlands of Sweden and Canada to the urban forests in Europe and America: a duck feather, a piece of granite, a reed tassel, a whale vertebra. Each a portal into a heartland.

As well as a main task of creating work for a ‘show’ at the end of the course, we set them a ‘lesser’ task for the weeks ahead: this one’s is to to voyage into the winter twilight. Next week I will be leading an equally liminal session from the shores of our dark oceans, navigating its shifts, while anchored by kelp holdfasts and sea kale roots. I won’t reveal the water task before the class, but here is a hint. It will involve saying thank you and getting your feet wet (and sometimes your whole body).

Because sometimes you have to take the plunge …

Thank you as ever for reading this post. On 14th December which is the start of the Halcyon Days, I’ll be sharing a piece about the ancestral fire practice that became the Dark Mountain book Eight Fires (more tasks!), The third step of The Labyrinth and the Dancing Floor will be published after the Winter Solstice at the end of the year.

1, from ‘The Miner’s Hotel’, Beyond Zipolite by Mark Watson

Charlotte, taking long walks for visceral encounters with mud, rain, white fingers, thorns and more: bravo. Your posts always find ways of connecting me with issues disturbing my mind in that moment. As a former accountant who can so well relate to Mark’s attention to the admin of life, I know the ledger of my own would make Ebenezer Scrooge proud. As I stuff drawers with browning tickets and receipts, all documented to emulate the Sumer amulets, I feel the weight I’m carrying, could it be Marley’s chains perhaps, and want to live more consciously paying witness to the real world of life and sharing its joys. I want to write more but excuse myself day after day that the routine of a well administered life must be preserved before all else. Time to upend this view and seek the currents that run beneath my feet.

Thank you for your writing. Keep going through the darkness of your winter and know your light shines brightly far below your feet showing the way forward to others.

Best wishes as ever……..Keith

As usual there’s a lot in here that speaks to me. The Sumatran ledger part of the essay brings to mind a song titled “Universal Applicant” by Bill Callahan from his album Apocalypse which has an overtly alchemical bent.

“Without work's calving increments

Or love's coltish punch

What would I be?

An animal-less isthmus

Beyond the sea”

And I love that you bring up Ebenezer Scrooge at the end. Dickens has been on my mind a lot lately as I see so many people online selling spells to curse Donald Trump, gain love, or offering other various classes in magick. Charles Dickens cousin just happened to open The Dickens Opera in the small city where I live in Colorado. Dickens father, mother and siblings were notoriously imprisoned in a debtors prison and young Charles put to work in a factory for his father’s debts. This is the mud and thorns he walked and was born to. His work changed the world, poor people who couldn’t read would pay to have his stories read to them as many lower class people had never heard stories that were for them before. Rather than aim spells at the “White CIS hetero Patriarchy” as I have seen Dickens knew that haunting them with what those life could be was more effective. Writing words that engaged the poor and made them want to read was more effective magic. (I do not claim to be a Dickens historian if any of this rings untrue to you.)

I’m not opposed to magick or spells but there’s a tendency for such folks to see themselves as magicians and bigger and more important than they really are. Dickens doesn’t have to look or act like a magician in any way but was a much more powerful and effective “wizard” than anyone I see selling spells for profit online. Words and stories can truly change our world.

Lastly thank you for this…. “What we need to know is that a large part of ourselves, that part that seeks out the comfortable places, doesn’t really want to find one. Because instinctively we know it will entail what the modern seer Gurdjieff once called ‘conscious suffering’. No one signs up for suffering willingly. It’s not the kind of suffering you can offload on friends and therapists either, because it’s happening in a realm that civilisation has no terminology for, even though we all feel it. The constriction of invisible bars around us, held in place by terror.”

I know myself well enough at this point to know I’m going to poke more than a few hornets nests and I am indeed afraid of the consequences to come and more-so am afraid of the suffering I will bring to my partner and whether we can withstand it as a couple…yet I’m fairly certain this is where I must go.

Thank you for sharing so much of your journey with Mark. It is truly inspirational.